While you were out–staring at the window for the 39th time wondering how private equity seems to have taken over the world, perchance?–relatively few have noticed, until the odd recent headline here and there, about the seemingly sudden arrival on the FinWorld scene of “private credit.” What debt is to equity, well, you know….

But many of you surely noticed the intrepid Patrick Smith’s recent piece, Rise of private credit has been a boon to Big Law. This market, call it “P/C” not “P/E,” consists of “loans outside of the traditional institutional bank lending apparatus,” as Patrick well describes it, and is growing rapidly:

- $500-million in 2015

- $1.4-trillion when the books closed on 2022

- And an estimated $2.3 trillion four years from now.

And, reminiscent historically of the elite white shoe Wall Street firms shunning wrong-side-of-the-tracks work like proxy contests, hostile tender offers, and distressed debt and junk bonds, which empowered the rise of firms like Skadden, Wachtell, and Latham (respectively), all now inner circle members in good standing of the power players. And the same dynamic seems to have already kicked in on the P/C side of the balance sheet:

Jeff Ross, chair of Debevoise’s finance group and member of its private equity and special situations practice, said the acceptance of private credit in more mainstream markets has changed the power dynamic—with both the law firms and the financial institutions that they work with.

“This is a meaningful shift in market players,” he said.

And as summarized by Ranesh Ramanathan, co-leader of Akin’s P/C group (ex-Kirkland):

The private credit market didn’t always attract law firms. … “It used to be shadow banking. Now it is in the mainstream.” He said the initial offerings for private credit were seen by banks, and law firms, as somewhat beneath them. “They (private credit lenders) started as mezzanine lenders, dipping lower than the banks would go,” he said.

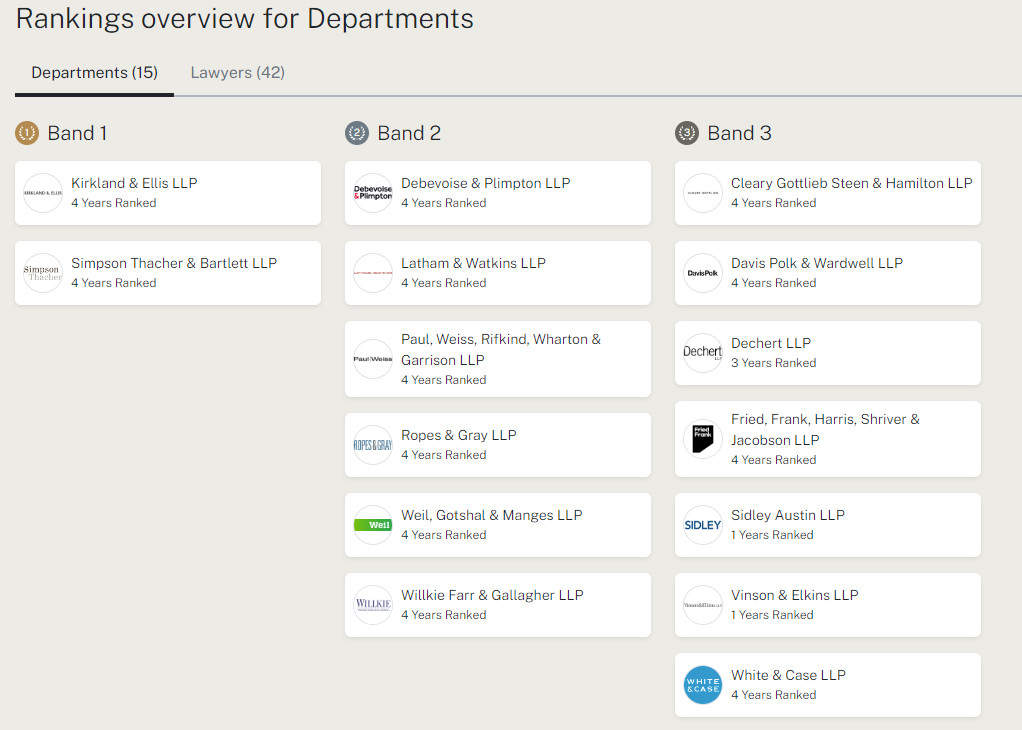

At least on the P/E side of the law firm rankings, the elite name brands still dominate. According to Chambers’ most recent firm rankings for “Private Equity–buyouts” (the only category of P/E that Chambers offers), the heavy hitters in New York look like this:

Not a second tier player or Johnny-come-lately in the crowd.

Could the emergence of P/C as a legitimate and substantial asset class in its own right entail an opening for one or more firms to change the composition of this lineup when Chambers gets around to recognizing it and reporting on it? No reason whatsoever why not.

But before we move on, let me share a development in my thinking that directly hinges on what I’m going to hypothesize below. A decade or so ago, as it became clear that Kirkland was moving into the Big Leagues, my primary reservation about their strategic approach was, “Almost all private equity almost all the time? Isn’t that a pretty high-beta way to concentrate your practice focus?” In other words, I was worried that if private equity as an industry/asset class shrank abruptly–these things happen regularly in FinWorld–Kirkland would go down with them. But since that wasn’t really my problem and one could always take refuge in the old Wall Street rubric that if you’re going to put all your eggs in one basket, “watch that basket like a hawk!”, I was content to sit back and watch and wait.

What changed is it’s safe to say that private equity is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, here to stay. When it started, it might have been a bet, but it was one Kirkland won in spades.

Read on.

Let’s widen the lens and talk for a moment about what this means in the larger context of FinWorld meets BigLaw. Shall we start with some data, as we’re fond of doing?

As the FT noted in a recent front-page story, there’s a “tremendous amount” of uninvested cash sitting in money market funds on the balance sheets of large US institutional investors (the usual lineup of pension funds, endowments, and foundations):

Top active fund managers say they are struggling to attract money from large investors who are holding back in the face of volatile markets and cash accounts offering the best yields in years. Institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments and foundations control billions in capital and are responsible for the majority of allocations to the biggest asset managers. Cash sitting in US institutional money market accounts now totals almost $3.5tn, according to the Investment Company Institute, [emphasis supplied]

One might well ask–and I hereby am–whether this $3.5-trillion is optimally deployed, parked as it is in money market funds? The answer cannot be yes; it has to be “no, not forever, not all of it.” So where will these super-sophisticated fund managers deploy it? Private credit, it seems, has to be a beneficiary. Talk about “dry powder;” this is 100 armories full of nothing but.

There’s more.

The ever-insightful Matt Levine over at Bloomberg (he writes the “Money Stuff” column four days/week) recently had this to say. It’s a subtle and perhaps underappreciated point, but Matt’s bottom line is P/E and P/C can be very attractive investments–by increasing portfolio diversification–even when they have bad years:

One very simple, very dumb model of private investments — private equity, real estate, private credit, whatever — is that they are like public investments except that their price is updated less often. This has two attractive features:

- Private investments have lower volatility: The stock market goes up some days and down other days; private investments are marked to market every quarter or whatever, which just smooths out a lot of variance. If you want lower volatility, just being told the price less often is … I mean … kind of that. We have discussed this feature before, and it is plausible that some investors pay extra for private-market investments precisely to avoid seeing prices change too often.

- Private investments are lagged. When the stock market drops, your private equity investments don’t. The stock market is a leading indicator: Stocks go down because the market expects cash flows to be lower in the future. Private valuations are more lagging: Private investments tend to be marked down when cash flows are actually lower. If the stock market is wrong and cash flows turn out to be fine, stocks will go back up and private investments will never lose value. (This is Point 1, about volatility.) If the stock market is right and cash flows go down, stocks will stay down and private investments will lose value, but later. This is good. It is a hedge. Your stocks go down one year and you are sad, but the losses are offset by your private investments whose valuations are still fine. Next year, your private investments finally go down and you are sad, but the losses are offset by the stock market, which, always forward-looking, is up again. Your overall portfolio has less volatility, because it consists of uncorrelated assets. [emphasis original]

Now, another perspective from which to evaluate any investment–debt, equity, LP interest, whatever–is how broad, knowledgeable, and objective are outside analysts evaluating that investment. With publicly traded companies, this is not an issue: Buy-side and sell-side analysts are all over public companies of any magnitude, with essentially zero barriers to entry and mandatory copious disclosure by the public companies themselves. You can argue there’s a herd mentality, and you’d have a point, but even that “bias” is universally understood and as widely discounted. Example: What self-respecting analyst, or analyst with an instinct for self-preservation at least, would put a “sell” rating on one of the Big Five Tech firms (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and now nVidia)? The point remains that open debate and discussion in covering public equities is unfettered and instantly discoverable.

When it comes to public debt, the situation is utterly reversed. The sources of the familiar AAA, AA, A, BBB-B, CCC-C, and D (S&P nomenclature) are the notoriously and existentially compromised rating agencies. Lest you have any doubt how I view the value of these ratings and the integrity with which they are issued: These agencies are hypocritical, shameless, self-serving, fatally conflicted, and impervious to criticism. But, let’s be frank, do investors care what these ratings are when making asset allocation decisions? Again, the invaluable Matt Levine pulls off the covers (he was writing about Fitch’s baffling and thoroughly uninformative downgrade of US Treasuries a few days ago:

Or whatever. Is that the point? What is the point of credit ratings? My general assumption is that the point of ratings is not primarily to tell investors which bonds they should buy. My assumption is that the point of ratings is primarily to serve some sort of quasi-regulatory function: Investors choose which bonds to buy, but they are constrained by mandates or marketing documents or regulation to only buy “investment-grade” bonds, and ratings determine which bonds are investment-grade. Or you do a derivative trade that requires your counterparty to post collateral, and the counterparty can post whatever collateral she wants as long as it is rated at least AA. Credit ratings are not there to inform investment decisions, but to constrain them, to limit the universe of bonds that an investor is allowed to own.

So yes, I know, lots and lots [and lots] of legal agreements specifically require “investment grade” collateral, but as many or more used to pivot on the LIBOR rate and when that went away nobody died. Still, it’s a complication that impedes and does not advance astute selection of issues and issuers.

Let’s turn to the private equity/credit side: Who’s evaluating the desirability of those investments? By and large, serious pro’s at the top of their game who have done this type of complex security analysis and valuation for their entire careers and would not be employed by Apollo/Blackstone/Carlyle/Evercore/KKR/[you name it] unless they were All Stars. Take your pick, but P/E and P/C have extremely well informed, highly motivated (and highly compensated) and hard-headed people examining their offerings.

And then there’s this: One more difference between public market analysts and private market analysts. Public analysts are expressing academic and somewhat deracinated or abstract opinions. A good call doesn’t make them richer (not legally, anyway) and a bad call costs them nothing (until it’s diagnosed as chronic). But private equity and private credit analysts have immensely more on the line. They’re deciding to whom to write checks and how many zeroes to put on those slips of paper. This instills a certain gimlet-eyed serious of purpose. Good enough for me.

Moreover, the “Classic” banking industry has not exactly been burnishing its reputation for solidity, reliability, and predictability, at least if you’ve been following the past few months of ugly acrobatics over there. Particularly in the regional banking market (Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic, Signature, etc.), if recent developments have proven anything, it’s that we have no clue in the United States how to regulate the public banking sector which takes retail deposits and operates on a fractional reserve model. No clue. For example:

- Who really believes the much vaunted “stress tests” are really tests or really stressful? Not even Jay Powell and Janet Yellen, if administered truth serum. (For that matter, I bet not Jamie Dimon.)

- Does anyone with even glancing familiarity at this recent circus of events believe the FDIC’s “ceiling” on deposit insurance of $250,000 means anything? I hope not.

- Other First World/advanced industrial nations (Canada, Germany, the UK by and large) have only a handful of banks; is the US’ 4,500+ really the right number and they’re all wrong? Possible.

- And even the straightest of straight-arrow Swiss, when it comes to banking, might not have it all figured out and buttoned up after all: Credit Suisse/UBS, remember?

There’s more. This from the front page of the FT a few days ago:

A lucrative age for private equity buyouts has ended, prompting an abrupt shift in the $4tn industry where returns will no longer be fuelled by rising valuations, the chief executive of Apollo Global Management warned on Thursday. “In the [private] equity business, this year has really marked the end of an era,” said Marc Rowan, whose Apollo is one of the world’s biggest private equity groups with $617bn in assets. A decade of “money printing”, fiscal stimulus and low interest rates that had pulled forward economic demand “is in retreat”, he added.

[And a bit further on, emphasis supplied:]This is a great time for private credit. This is not [just] a quarter that’s a great time for private credit, this is a secular change. Not only do we have higher base rates and regulatory change and change in market dynamics, we are in the beginning of a secular shift in how credit is provided to businesses and a shift that I believe will continue to gather speed.

To cut to the conclusion:

Maybe the venerable institutional banking industry is not the FinWorld category you want your law firm joined to at the hip. What if that was yesterday and maybe it’s P/E and now P/C. It doesn’t seem to have hurt Kirkland too much, now does it?

I absolutely enjoyed every word of this article. Thank you, Bruce, for always offering such an astute view of the (legal and banking) world. And now, to share this with some of my lawyers who focus on credit, not equities…

You are so entirely welcome! Thoughts like yours from readers are unbelievably heartwarming, gratifying, and need I mention motivating?

I would like to believe that one function Adam Smith, Esq. can perform is to apply our decades of experience from general business–P&G, J+J, global media/communications agencies, Wall Street, corporate BigLaw, macro- and micro- Econ, and business history–to our beloved and exasperating industry.

Thanks again. (And let me know if those lawyers “get it.”)

What about Fried Frank? It’s a third tier law firm?

Talk to Chambers!