The following article is by Janet Stanton, Partner, Adam Smith, Esq. LLC.

Quite simply, our reason for exploring the non-equity tier is that (a) there has been explosive growth in that cohort and (b) we’ve not seen recent, comprehensive examination of this phenomenon.

To be clear, what we’re not talking about here are the more specialized types of non-equity categories such as glide paths for retiring partners or exceptions for highly arcane but never “go-to” destination for clients (think: specialists in the esoterica of M&A taxation, etc.) – both of which make great sense, but do not represent a significant proportion of lawyers at any given point at law firms.

What we are talking about is a level above associate, but below equity partner, variously referred to as non-equity partners, income partners or non-share partners.

And, with that…

Let’s start with some data (as we often do)

The classic conception of the typical law firm structure is of a pyramid, with a large cohort of associates at the bottom and a far smaller triangle of partners at the top. This model had its genesis in the legendary Cravath System and has persisted stubbornly in our imaginations despite its increasing disconnect from the facts.

In reality, the non-equity tier has grown dramatically and steadily. In the early 1990s, fewer than 5% of AmLaw lawyers were non-equity partners (NEPs); as of 2022 (latest available data), fully 16% are.

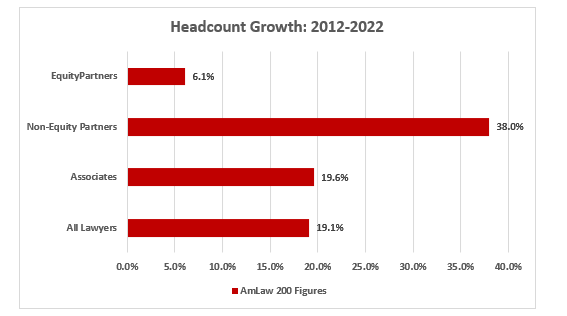

Growth in the non-equity partner tier has dwarfed that of the other cohorts over the past 10 years; double the rate of already impressive total headcount increases:

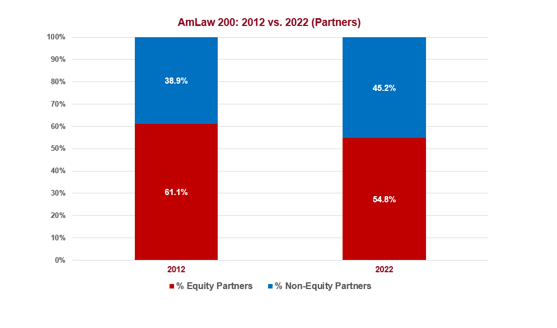

This has resulted in a significant shift in the composition of the partner tier (see below). This trend is showing no sign of abating; all research sources we tapped into and those we interviewed unanimously agree. At this rate, in the not-too-distant future, NEPs will constitute the majority of partners in the AmLaw. Already NEPs outnumber EPs at 73 AmLaw firms.

That said, this striking reshaping of the market hasn’t garnered much attention nor examination.

Of note, over this same 10-year period, the percent (%) of associates of total lawyer headcount in the AmLaw 200 has held steady at 59% (in both 2012 and 2022).

What’s behind this change?

In our view, another highly significant, yet largely unexamined, development in Law Land over at least the past 20 years has been the inexorable shift in what the expectations for an equity partner are. Previously, lawyers were often elevated to equity status on the basis of technical proficiency (or time in grade). Now, business generation is, as one recruiter described it to us, “the first, second and third criterion” for elevation to the equity tier. Though some outlier firms were mentioned, this view was unanimously espoused as an industry standard in all of our interviews and comports with our own study of the industry.

The result? The goalposts for equity partnership have been permanently moved back.

The job of an equity partner now is not just broader but distinctly different: To marshal, oversee, and organize teams working on client engagements and to make a robust financial contribution to the firm by attracting new client business and be a good corporate citizen at the firm.

Thrusting an associate directly into full equity status, and judging them immediately by their performance in roles they have never assumed and have no training for, invites disaster all around. A reasonable transition period where associates are deemed “partners” to the outside world and are given time, training, and resources to develop their business origination skills, takes a large step towards resolving the problem—and the mechanism is an intermediate tier. [1]

Therefore, it’s not surprising to us that some highly proficient, productive and desirable lawyers have neither the skills nor stomach for business generation; as one of our interviewees put it, “the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.” And, it would seem to us highly counterproductive to lose these fine lawyers.

Further on this point, as client legal needs have become more complex, firms generally require (and clients expect) larger teams to service these needs. Senior, accomplished non-equity partners do and will play an increasingly critical role in these circumstances. As one COO put it, “for big clients with big cases, it’s important to have midlevel ‘partners’ with authority, gravitas and credibility.”

These two developments could argue for two, highly differentiated tiers of non-equity partners coming out of a firm’s associate ranks; an EP apprenticeship tier (time-limited) and a permanent NEP tier (both are discussed below).

We are in no way suggesting that firms create these two tiers (or one or the other or neither). We do always urge individual firms to stay abreast of market dynamics and to develop appropriate responses that are consistent with their strategies, circumstances, history, capabilities, aspirations and culture. This is simply pointing out two significant market shifts and how firms, in the abstract, might capitalize on or respond to them.

Another change occurred in 1985, when American Lawyer began publishing reported revenue and profits at the nation’s top firms, including average profits per partner (PPP). One of the many (unfortunate, in our view) consequences of this has been to provide firms with a disincentive to elevating lawyers to equity status, lest their profit pool be diluted and PPP lowered.

To us (and others), introducing or expanding a non-equity tier solely for the purpose of boosting or propping up equity profits is, at best, a short-term strategy. Many we interviewed characterized this as “cynical.” This may be part of a macro culture tilted toward opportunism and/or expediency (what some refer to as “hotels for lawyers.”). Folks will recognize it for what it is. And, longer term, promising up-and-comers at those firms will depart and more desirable recruits/laterals may be dissuaded from joining, resulting in an inevitable, if albeit slow, decline.

This development, which has undoubtedly contributed to increased lawyer mobility, in combination with lengthier stints for associates prior to elevation also supports creation of a non-equity tier, in part, as a defensive (retention) mechanism.

Let’s look at some financials

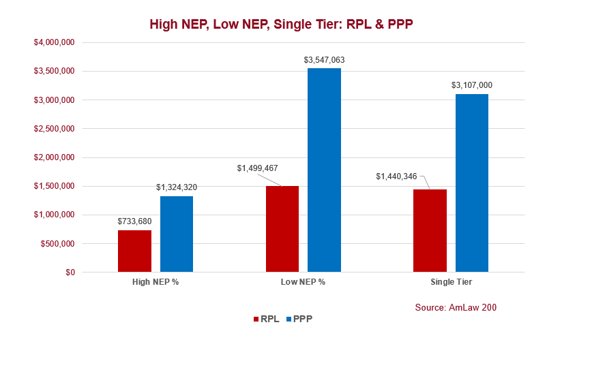

The number of single-tier firms in the AmLaw stands at 27; therefore, fully 86% of AmLaw firms have at least two tiers of partners. We looked at AmLaw single-tier firms and those with (a) a higher proportion of NEPs and (b) those with lower. And, though these latter two tranches perform vastly differently, it would be foolish in the extreme to assume any correlation, nay causation, between financial performance and their relative use of NEPs; there are simply a myriad of other factors that influence financial performance (e.g., practice areas, sector focus, geographical footprint, client makeup, quality of leadership, strategic rigor, incentives, governance, operational discipline, financial hygiene, culture, etc., etc.).

That said, here are the numbers.

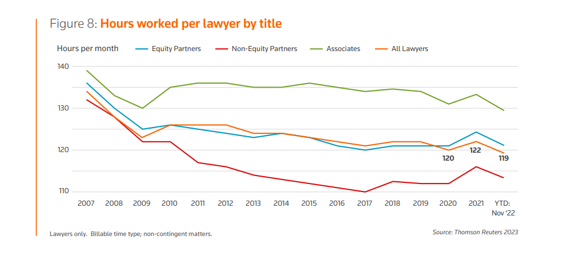

As it turns out, non-equities, as a whole, are the least hard-working category (see below from Thomson Reuters’ longitudinal Peer Monitor reports). Though there has been a steady, industry-wide decline in hours across all titles for over a decade and a half, the decrease for non-equity partners has been the steepest by far (having started out in 2007 fairly close to the other groups). One hypothesis is that as the cohort was introduced (and grew) at more firms, the quality and rigor of how the cohort was managed (or more likely not) varied widely by firm, with many firms ending up with a not-insignificant number of lawyers basically supporting themselves, but not really contributing to the firm.

Too frequently, non-equity status becomes a parking lot for “pretty good” senior associates with no real champions nor noticeable rainmaking skills. To enable this, firm management is displaying a preference for avoiding awkward conversations over taking necessary action. Another corrosive outcome of mis- or, perhaps, better stated non-management can include associate frustration as when a bloated NEP tier impedes their development/advancement and/or hoards work that would more appropriately be handled at the associate level.

Considerations for non-equity tiers

Overall, there is broad consensus that non-equity tier(s) can be very beneficial to firms and to individuals – but this was invariably and immediately followed by caveats on what can go wrong and what to watch out for (which we’ll get to in a bit).

On a macro basis, most agree on the overall potential benefits of non-equity tiers. These include:

- Further lawyer ”maturation” to hone business generation skills. Non-equities are able to market themselves to the external marketplace as partners. There is also internal recognition, as one recruiter reported, “it’s a stamp of approval.”

- Another recruiter added, “everyone loves promotions – they can tell their spouses and friends; it’s a real boost.”

- Being able to retain equity partner track associates who might otherwise be sympathetic to entreaties from other firms offering them the title.

- Being able to hold onto highly productive, desirable lawyers who have neither the inclination nor skills to become a rainmaker. Complexity will only continue to ratchet up, and as discussed, clients value the contributions from solid mid-career “partners,” who also bring a greater sense of stability to the firm.

- All recruiters agreed that an NEP tier is very useful in recruiting, as one said, “titles matter.”

- Increased leverage can boost profitability, but as discussed, this should not be the only motivation.

- Non-equity tiers can provide firm management flexibility in the event of a downturn or market shift; the process for removing equity partners can be thorny.

- And, as discussed – providing slots for highly specialized attorneys who service the firm’s main economic engines or a glide path for retiring partners.

What could possibly go wrong?

On the flip side, we see no inherent negatives to non-equities. That said, there are highly consequential implications firms should consider in relation to their own goals, strategies, circumstances, culture, capabilities, and aspirations. Moreover, there are some very definitive ways firms have botched implementation.

The inattentive, laissez faire approach of many firms is probably the biggest mistake firms make. This was succinctly encapsulated to us by the ex-Chair of a global, AmLaw 50 firm, “Our income partner class was viewed more as another step in the associate’s progression. There was no major move in billing rates, and more subdued expectations for billable hours [versus equity partners].

He continued, “Most importantly, we didn’t have the guts to move income partners out after a period of time. Thus, the income partner class grew and we thought we could handle those who didn’t perform at a level that would lead to their promotion to equity by means of their compensation. Frankly, less talented or ambitious people are perfectly happy to work at $300-400K. They pay for themselves but don’t really contribute that much to equity partner profits. When it comes time to move them on, it’s hard because they have developed relationships with inside counsel.” (emphasis ours)

His bottom line, “The category can make great sense for both the lawyer and the firm, but the firm needs to be better than I was at managing the situation.”

This all underscores the reality that different revenue models require different business models. One COO explained that two-tier partnerships require more active management than single-tier. For example, generating revenue from leverage versus from excellent outcomes requires more management including, for example, a more robust financial/tracking/HR infrastructure, near-constant communication of expectations – and especially the discipline of pruning folks when necessary.

A bit more on the EP apprenticeship tier (time-limited) and a “permanent” NEP tier

As discussed above, evolving market dynamics could argue for two, highly differentiated tiers of non-equity partners coming out of the associate ranks. To recap, the EP apprenticeship tier would be intended to prepare future equity partners, the permanent tier would serve as a valued and respected role for accomplished, desirable lawyers who have neither the desire for nor interest in business generation.

How might these two cohorts be differentiated?

Many of the criteria for elevation from associate to non-equity status would be the same for both. These criteria were generally agreed to be characteristics such as: smart, technically proficient, likeable, strong relationship skills (with clients and internally), leadership and management capability, organized, commitment to good firm citizenship – and the like. The difference here would be an interest in and propensity for business generation among the EP apprenticeship candidates.

The EP apprenticeship track includes two “gates” between associate status and full equity partner with explicit performance and timing parameters. We think the EP apprenticeship experience should hew as close to the equity experience as possible (but of course augmented with training and mentoring, etc.). What might this mean? We think it would be wise, for example, to require some (modest) level of capital contribution, include this tier at partner meetings and maybe, even, symbolic participation in voting. They should begin to contribute meaningfully on key committees and have access to firm financials, though not individual compensation.

Permanent NEPs should be held to consistently high performance standards and remunerated accordingly. In other words, they’re permanent as long as they’re performing well. Chronic underperformance (i.e., not just one bad year) and/or anti-social behavior should have real consequences. [2] In fairness, this is probably the more challenging tier for law firms to manage because hewing to standards over time requires balancing a variety of quantitative and subjective factors. But, let this slide at your peril lest you end up with an ill-defined assortment – much as the ex-global Chair described above.

Closing thoughts for firms

With all that, firms need to provide clear-eyed answers for the following – whether firms are already multi-tier or considering expanding beyond a single tier:

- Make sure you know why you have/want non-equities and exactly what purpose they should serve. You have permission to re-examine those purposes and that strategy as the priorities of your firm evolve.

- Also be clear about the developmental role of the NEP tier(s) in the career of lawyers.

- What are the guidelines for entry into and, critically, for exit from those categories?

- Clarity, transparency, repetition: Tell everyone what the deal is, remind them frequently but cordially, make sure all are walking the talk.

- Do you have the infrastructure to effectively manage a non-equity tier? And, as our ex-Chair discussed above, “the guts” to prune the non-equity ranks when that is called for?

- Keep your eye on those clocks and those numbers.

As we’ve seen, the market has shifted permanently; firms need to assess these, and other, changes in a clear-eyed manner – then respond with intentionality and resolve in a way that is consistent with who they are.

As such, we are reminded of this from John Maynard Keynes…

“When the facts change, I change my mind – what do you do, Sir?”

[1] A sensible approach to this new reality, would be to initiate some sort of training and preparation earlier – while lawyers are still associates – but this doesn’t seem all that common in Law Land (unlike in Corporate Land).

[2] Frankly, anti-social behavior by anyone should always have consequences and should not be tolerated.

You could convince me that the income partner ranks could be policed more rigorously at the vast majority of AmLaw 100 firms. You can’t just shrug your shoulders and manage that tier solely through the comp system. But it seems like a lot of firms do just that, assuming some bare minimum level of performance.

Bifurcation might make some sense for some firms because it let’s you set up different incentive structures for people with different motivations, which is harder to do when everyone is lumped together under one title. Equity-lite with a cash contribution is an interesting concept. Although if I’m putting money in, do I get some tangible upside (other than just maybe I make equity at some undetermined point down the road)? Do I have a fractional vote on the list of major decisions?

Lots of firms have already addressed the “pretty good” senior associate problem with the proliferation of the counsel title. That’s a place to park profitable lawyers with partner-level skills who don’t want the business development responsibilities. And maybe season some of them to make the jump to income partner with the attendant training/professional development. There can be tiers within that title too.

I think you hit right on it though. Yes, this is by and large a profitable population for most firms. Obviously, this wouldn’t exist if that wasn’t the case. But even more than that, clients like this population. They provide real depth to the relationship, which large repeat, institutional clients find attractive. It’s hard to find good teams.

Yep – think you’re right.