Jamie Dimon’s annual letter to shareholders, which comes out as part of the JP Morgan Chase annual report, was published about two weeks ago. At 42 pages, it takes more than a passing skim-over to digest, but. It is almost universally read among business leaders, and I thought for those of you who hadn’t seen it or hadn’t studied it, a few highlights that might be particularly germane to Law Land were worthy of notice.

I won’t dwell on the nasty and brutish global backdrop 2022 presented—the Ukraine invasion, China’s obstreperous behavior militarily and geopolitically, increasingly widespread resignation to permanent unbridgeable divides in our own country—but devote our time here to Dimon’s focus on the road ahead.

Understandably, Dimon starts with a longish section on JPMorgan Chase’s performance (can you say “strong?”), enduring principles (none surprising), specific issues facing his firm (climate, AI, and turmoil in the banking industry). As for the last, he notes pointedly that “simply satisfying regulatory requirements is not sufficient,” and criticizes regulatory watchdogs rather sharply vis-à-vis the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, Credit Suisse, and associated weaknesses and vulnerabilities that were suddenly exposed (“most of the risks were hiding in plain sight” [emphasis original]).

It’s worth a moment to note how he elaborates on this:

It is unlikely that any recent change in regulatory requirements would have made a difference in [these failures].Instead, the recent rapid rise of interest rates placed heightened focus on the potential for rapid deterioration of the fair value of HTM [hold to maturity] portfolios and, in this case, the lack of stickiness of certain uninsured deposits. Ironically, banks were incented to own very safe government securities because they were considered highly liquid by regulators and carried very low capital requirements. Even worse, the stress testing based on the scenario devised by the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed) never incorporated interest rates at higher levels. This is not to absolve bank management — it’s just to make clear that this wasn’t the finest hour for many players. All of these colliding factors became critically important when the marketplace, rating agencies and depositors focused on them.

As I write this letter, the current crisis is not yet over, and even when it is behind us, there will be repercussions from it for years to come. But importantly, recent events are nothing like what occurred during the 2008 global financial crisis (which barely affected regional banks).

His thoughts on how regulators failed to foresee, much less forestall or avoid, failures like SVB and Credit Suisse, is pointed and damning:

Regulation, particularly stress testing, should be more thoughtful and forward looking. It has become an enormous, mind-numbingly complex task about crossing t’s and dotting i’s. For example, the Fed’s stress test focuses on only one scenario, which is unlikely to happen. In fact, this may lull risk committee members at any institution into a false sense of security that the risks they are taking are properly vetted and can be easily handled. A less academic, more collaborative reflection of possible risks that a bank faces would better inform institutions and their regulators about the full landscape of potential risks.

We have written periodically about the growth of the “non-bank bank” sector of the financial services industry, as it has direct and immediate implications for BigLaw. (Kirkland’s fortress p/e practice, for example; I trust I need say no more?) But we had not seen it longitudinally quantified in such concise form as Dimon provides:

Corporate Governance & Management Lessons

If any leader in the financial services sector could lay claim to “statesman,” Dimon would have to be on the short list of candidates. That’s why I deemed it worth your while to excerpt some of his reflections on lessons for management. The first has to do with human capital and the use and abuse of financial models:

Increasingly in the modern world, many valuable things are not reflected on our balance sheet in generally accepted accounting principles — for example, previously expensed intellectual property or extraordinary human capital. At the end of the day, human capital is the most valuable asset. Think of a great athlete, a great lawyer or a great artist. It’s not simply the equipment — it’s the extraordinary training and talent of those involved, as we’ve also seen with the U.S. military. And sometimes it’s not the individual but the highly coordinated activities of the team that deliver the championship.

Finally, if any value is based upon models, one must really test the sensitivity of the outcome against changes in assumptions. Understanding the range of potential outcomes may be far more important than the point estimate created by a model. In some cases, you can have an excellent average outcome, with a chance of death.

Dimon takes a very dim view of some of the recent trends in how public company corporate governance is being transformed: Rather than its historic role as providing internal hygiene and a moral compass to the corporation, it has been increasingly transformed into a means to ends deemed laudable and worthy by self-selected outsiders with a public sector rather than a private sector orientation. Take another look back at that “non-bank banking” table:

I have written before about the diminishing role of public companies in the American financial system. They peaked in 1996 at 7,300 and now total 4,600. Conversely, the number of private U.S. companies backed by private equity firms has grown from 1,900 to 11,200 over the last two decades. And this does not include the increasing number of companies owned by sovereign wealth funds and family offices. This migration is serious and worthy of critical study, and it may very well increase with more regulation and litigation coming. We really need to consider: Is this the outcome we want?

There are good reasons for such healthy private markets, and some good outcomes have resulted from them as well. The reasons are complex and may include public market factors such as onerous reporting requirements, higher litigation expenses, costly regulations, cookie-cutter board governance, less compensation flexibility, heightened public scrutiny and the relentless pressure of quarterly earnings.

With intensified public reporting, investors’ growing needs for environmental, social and governance information and the universal proxy — which makes it very easy to put disruptive directors on a board — the pressure to become a private company will rise. Corporate governance principles are becoming more and more templated and formulaic, which is a negative trend. For example, sometimes proxy advisors automatically judge board members unfavorably if they have been on the board a long time, without a fair assessment of their actual contributions or experience. And some simple, sensible governance principles are far better than the formulaic ones. The governance of major corporations is evolving into a bureaucratic compliance exercise instead of focusing on its relationship to long-term economic value. Good corporate governance is critical, and a little common sense would go a long way.

I took the liberty of such an extensive quote both because Dimon’s bluntness, and his firm grasp of the law of unintended consequences, are extraordinary within the reams of public company CEO statements, and because BigLaw should have a thoughtful and coherent view of the goals of corporate governance and the backbone to stand up for them.

Geopolitical Issues

For my money, the most pointed and thought-provoking part of his letter. It’s a commonplace, he observes, to say that we are living in times of uncertainty. All times are such times. But this time, Dimon says, actually is different; he foresees a “once in a generation sea change, with material effect.” [emphasis his]

What would this new landscape look like? Not pretty:

Less-predictable geopolitics, in general, and a complex adjustment to relationships with China are probably leading to higher military spending and a realignment of global economic and military alliances.

Higher fiscal spending, higher debt to gross domestic product (GDP), higher investment spend in general (including climate spending), higher energy costs and the inflationary effect of trade adjustments all lead me to believe that we may have gone from a savings glut to scarce capital and may be headed to higher inflation and higher interest rates than in the immediate past.

Essentially, we may be moving, as I read somewhere, from a virtuous cycle to a vicious cycle.

Dimon’s pessimistic outlook—one which I increasingly share—strikes me as resting on solid observations:

- Fiscal stimulus is alive and thriving: The US federal government deficit was $3.1 trillion in 2020, $2.8 trillion/2021, and $1.4 trillion/2022. For the next three years and then as far as the eye can see, the estimates are in the range of $1.4–$1.8 trillion. With understatement, Dimon calls these “extraordinary numbers” (twice).

- Q/tightening now is trying to follow over a decade of Q/easing. Real interest rates here and in Europe were solidly <0%, driving up asset prices virtually across the board, from good old stocks and bonds to real estate and of course the high-profile crypto sector.

- Then of course we have the first real ground war in Europe in 80 years, which, putting aside the incalculable, vicious, pointless, and heartrending human suffering, has economic consequences as well on grain and energy markets.

So what’s to be done?

Well, being a practical fellow, Dimon has a few specific suggestions, all of which are shockingly sensible, founded in the bedrock of common sense, and depressing in how unlikely they may seem of achievement in today’s polarized environment:

- A US growth strategy: The enemies of strong and sustainable growth are “ineffective education systems, soaring healthcare costs, excessive regulation and bureaucracy, the inability to plan and build infrastructure efficiently, inequitable taxes, a capricious and wasteful litigation system, frustrating immigration policies and reform, inefficient mortgage markets and housing markets and housing policy, a partially untrained and unprepared labor force, excessive student debt, and the lack of proper federal government budgeting and spending.” Quite the list! But who can honestly say this bill of particulars is wrong?

- An industrial policy. No, we have never had such a thing, and yours truly is deeply skeptical that any individual or group small enough to actually make decisions is wise enough to “pick winners,” in the notorious but apt phrase, much less insulate it for more than the briefest moment from rent-seekers and log-rollers, but Dimon makes a valiant effort to be modest and targeted, to safeguard national security and counter “unfair” competition. There you have it.

- Fix income inequality Serious and well-funded apprenticeship programs, expansion of the EITC, and sustained work skills training. I must confess it’s shameful in the United States to have full-time workers at McDonald’s or Walmart qualifying for food stamps. Dimon apparently thinks this borders on disgraceful, and it’s hard to disagree.

- Finally, the US should lead on designing a “comprehensive global economic strategy.” If you believe, or hope, that such a strategy could have teeth and be meaningful to countries and peoples’ lives, then Dimon is surely right when he says “Only America has the full capability to lead and coalesce the Western world, though we must do so respectfully and in partnership with our allies. Without cohesiveness and unity with our allies, autocratic forces will divide and conquer the bickering West. America needs to lead with its strengths-not only military but also economic, diplomatic and moral.”

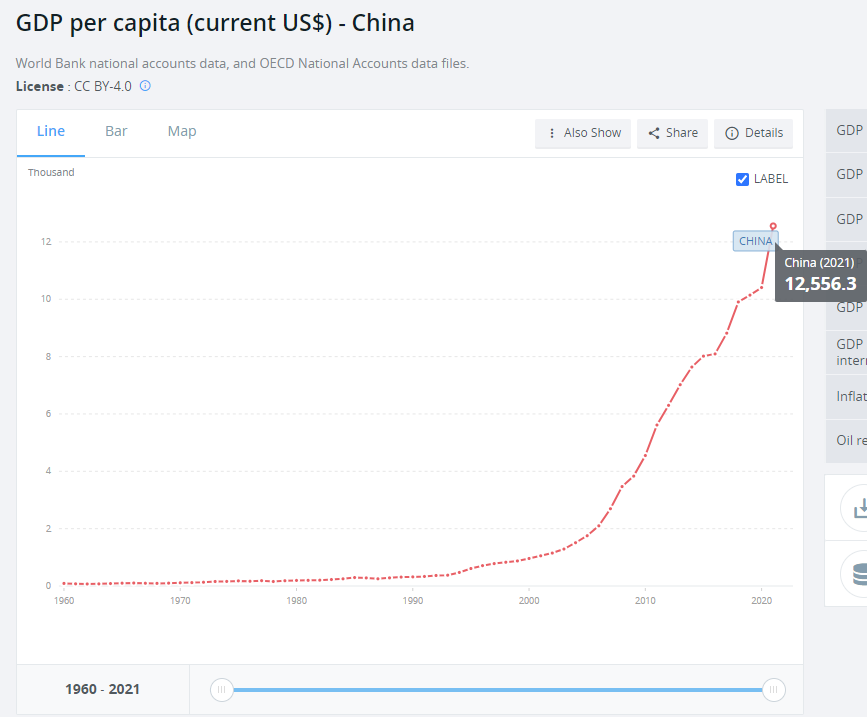

Refreshingly, he would include not just the compulsory elements such as strengthening alliances but “far more dynamic development finance for emerging markets.” If China’s historically astonishing rise in GDP per capita over the past 60 years demonstrates anything, it’s that if emerging markets can have access to financing—and private sector ownership remains strong and secure—miraculous changes in living standards can ensue:

Your editor offers no opinion into how sustainable the “strong and secure” “private sector ownership” is within China.

What to make of all this?

I have no idea what Dimon himself would say if asked to boil his views down to a pithy phrase, but it might be along the lines of “storm warning.”

He does allow himself to vent at the antiquated systems and ossified procedures of “the administrative state,” and I imagine many of you would sympathize:

Like most Americans, I get frustrated with the mediocrity and bureaucracy of the massive administrative state. We accept it too readily. And it damages the confidence we have in our own country. I have enormous respect for the people who work for the U.S. government, but we simply don’t invest enough in making it more effective. Some examples are: antiquated systems at the Federal Aviation Administration, United States Postal Service and Internal Revenue Service; inefficient ports and crumbling infrastructure; an ineffective immigration policy; policies that prevent affordable housing and leave apartments vacant; policies that hurt Puerto Rico; tenure versus merit-based compensation and promotion; and work rules that dramatically reduce efficiency. We have a vast system with a lack of accountability and proper reporting. And usually when reports are issued, they only address how much money was spent — not, for example, how many highway miles were built, in what time period and at what cost. Government, which is 20% of the economy, seems to be getting less productive over time, unlike the rest of the economy. In addition, we have too much litigation — this is the bureaucratization of America — think Europe

This is more than an “academic” observation, because if we are to act as one unified society and nation to address some of the challenges he has outlined—and others I’m sure you would be happy to cite in your own minds—we need a national effort. At the moment, it’s almost unthinkable to believe that could be spearheaded by the federal government. And if not them, who?

I will close with two jolly views about our economic future coming from entirely disparate sources: First, the IMF just substantially downgraded its projection of global growth:

The baseline forecast is for growth to fall from 3.4 percent in 2022 to 2.8 percent in 2023, before settling at 3.0 percent in 2024. Advanced economies are expected to see an especially pronounced growth slowdown, from 2.7 percent in 2022 to 1.3 percent in 2023. In a plausible alternative scenario with further financial sector stress, global growth declines to about 2.5 percent in 2023 with advanced economy growth falling below 1 percent. Global headline inflation in the baseline is set to fall from 8.7 percent in 2022 to 7.0 percent in 2023 on the back of lower commodity prices but underlying (core) inflation is likely to decline more slowly. Inflation’s return to target is unlikely before 2025 in most cases.

Growth @ < 1.0% excites no one.

And then there’s Paul (Elliott) Singer, founder of Elliott Management, one of the world’s most successful hedge funds, who sat for an interview with The Wall Street Journal about a week ago. In a nutshell:

“I think that this is an extraordinarily dangerous and confusing period … There’s a significant chance of recession. We see the possibility of a lengthy period of low returns in financial assets, low returns in real estate, corporate profits, unemployment rates higher than exist now and lots of inflation in the next round.”

And, for good measure, he thinks it will end only with a credit crunch—think the GFC of 2007/08 redux—or hyperinflation. Capitalism, he drily observes, can survive the former but not the latter.

So, having read this, innocently sitting in your office/office or your home/office and trying to mind your own business, what counsel can one offer?

- Pull out that recession scenario plan and update it or write it from scratch if you, ahem, can’t remember where you filed it last time.

- Be prepared for yet another round of heightened volatility, if nothing else. Practice areas will go in and out of vogue, sometimes the ones you least expect to bounce around. Some skilled lawyers will be maxed out on work and demand for their services, others through no fault of their own will find themselves on the figurative bench, looking for distractions and stroking out with anxiety while they’re cleaning their pools and grooming their tennis courts.

- Your firm’s performance will be, perforce, volatile and unforeseeable. Repeat after me: This is no one’s fault. No one is “responsible” for this. No one is to blame, no one should apologize. But you d($(%( well better tell your partners, associates, and professional staff that they should brace themselves for a rough ride. Trees—even the species law firmaceae—do not grow to the sky.

Aren’t you glad you read this far?