If we’ve heard that once over the last couple of months…..

It’s getting to the point where we wonder if those words threaten to become the lyrics of the Great Summer of 2021 Breakout Pop Hit Single. Actually, we leave that to the Great Clive Davis and the demigods of pop music.

Oh, and did you know Davis graduated from Harvard Law and practiced briefly in NYC? (Just goes to show “you can do anything with a JD”–at least if you’re Clive Davis.) He was an associate with Rosenman Colin before going in-house with one of Colin’s big clients, which happened to be named CBS Records.

But before we completely lose control of this thread, doesn’t this demand an economic explanation? How can it be, 15 months after the start of the gravest global pandemic in a century, that BigLaw, SmallLaw, EliteLaw and MiddleMarketLaw, in every geography we’ve heard from, are all “insanely busy?”

First and most important–yes, beyond the economic hypothesis I’m going to offer–let us not make light of the consequences: Working hard may be part and parcel of the BigLaw bargain, but the loads have been extreme, the duration seemingly endless, and the external forces contributing to anxiety, insecurity, burnout, and unhealthy habits unprecedented.

This says it all (from “Unsustainable”: Unprecedented workloads are taking a toll on corporate teams, just published in The American Lawyer)

“I’m seriously worried about the mental health of my team going forward—the rate we’re going at is unsustainable. The work just keeps coming.”

So says a senior corporate partner at one of the U.K.’s leading law firms, as others across the London legal market agree: the wave of mandates landing at law firms’ feet, particularly those from private equity clients, is becoming too much for junior lawyers to handle.

Partners say that top private equity clients are taking advantage of a glut of dry powder and their relatively stable position in the market to do a raft of deals all over the world, which, after a dearth of deal-making last summer brought on by the pandemic, was more than welcomed by law firms looking to hedge their own businesses.

But as the mandates kept coming, and with no sign of a slowdown on the horizon, corporate lawyers’ enthusiasm for work has steadily petered out. And now, several say, they and their teams have nothing left in the tank.

Corporate partners at two major firms in London say that they’ve even had to turn down work from key clients because of the workload.

“We were all exhausted by March,” says the U.K. firm partner. “By that time we’d already been busy since August with a minimal break for Christmas. I personally worked all through the Christmas holiday, with a break for Christmas Day morning and evening.

“Our Q1 was the busiest on record. No sooner had we gotten through the first processes of one deal than another request was incoming. It was chaos, but welcome chaos, as in the backs of our minds we wondered whether another downturn could be on its way. The sense was that we didn’t want to look a gift horse in the mouth.”

“Now my team are looking withdrawn, they’re saying they have anxiety, and none of us have had a proper break in months. I know of many others across the city who say the same thing.”

Let’s investigate.

Here’s some helpful data Courtesy of the WSJ:

- New business creation is at the highest pace the data series has ever seen.

- The rate at which workers are quitting their jobs–expressing confidence in the labor market–is the highest going back to 2000 at least.

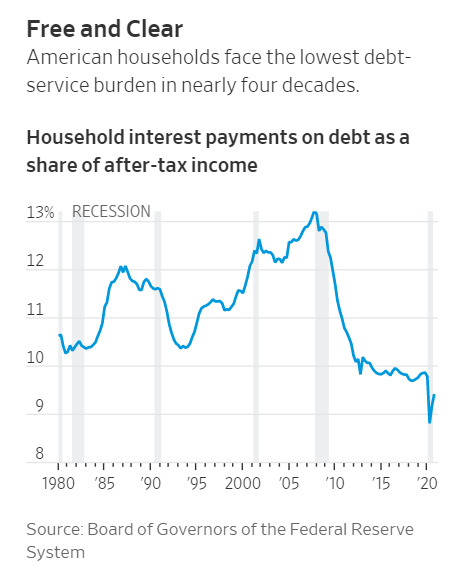

- American household debt burdens (as a share of after-tax income) are bouncing around their lowest levels since 1980, when this data series began.

- The DJIA is up nearly 20% from its pre-pandemic peak.

- Home prices nationwide are up 14% over the same period.

- And the consensus of economists surveyed by the WSJ calls for the economy to grow faster than the pre-pandemic forecasts.

The greatest differences are two. First, all recent recession recoveries going back 30 years have been “jobless.” Weak consumer demand kept companies from hiring back workers they didn’t need which kept workers from finding jobs which kept them from having money to spend which caused weak consumer demand. And second, household incomes and most of all balance sheets did not just hold up strong during the Great Covid-19 Recession, they strengthened.

What’s going on?

Conventional recessions–that is to say, the only type any of us alive have ever experienced before this–invariably resulted from some building imbalances in the macroeconomy, and when the inevitable rebalancing began, it tended to be protracted and painful as the repercussions flowed through GDP, CPI, unemployment rates, etc. (Inflation out of control in ’79-’80, the housing bubble in 2008, etc.) But this recession was caused more by governments worldwide ordering their countries to slam on the brakes. Or, you could think of it as one massive and extended worldwide rolling blackout. Everything shut down, to be sure, but the engines of production, and capital and human assets, were completely undamaged.

Bring the power back on or repeal lockdowns and restrictions and, voila.

No, of course it’s not that simple. Interdependent sectors won’t all come roaring back in perfect synchronization. (See: Chips, lumber, many categories of indispensable consumer packaged goods; not to mention the enormous hotels/-restaurants/-travel/-entertainment/-performing arts industries.) But they will all get there even if it’s patchy and stop/start for awhile. And many of the sector-specific shortages and supply chain bottlenecks have been self-inflicted, as “just in time” manufacturing has shown it can bite you back, and other major supply sectors [remember chips and lumber] misjudged how severely they should cut back production.

Meanwhile, remember those consumer balance sheets? Interest payments on debt as a share of after-tax income are at 40-year lows:

Debt in delinquency has dropped to 3.1% in 1Q21, the lowest in over two decades of recordkeeping and compared to 11.1% as we emerged from the Great Financial Meltdown of 2009.

So what has all this to do with Law?

Yep, the economy is likely going to roar for a few years here. Inflation and interest rates bear watching over say 18-24 months out. But there don’t really appear to be any structural barriers to robust top-line GDP growth.

Moral of the story, don’t bet against the American consumer?