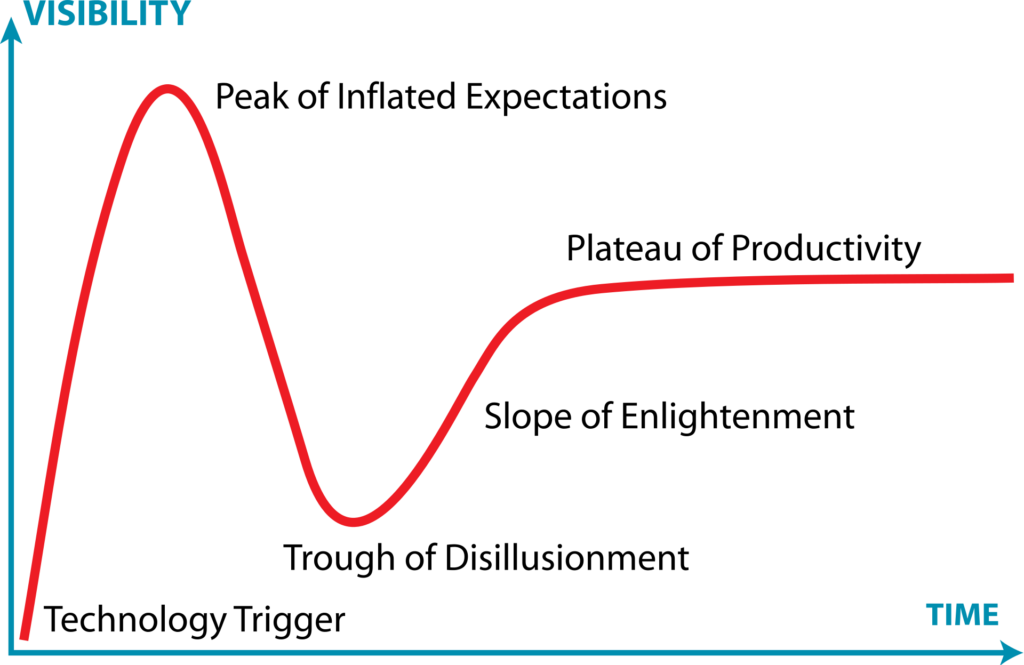

AI in law is the new Innovation. The industry press can’t write enough about it, law firm leaders and GC’s have to be seen as in the vanguard, vendors (of course!) can’t tout it enough, and no one, it seems, can worry about what it means for their future career enough. In terms of Gartner’s classic hype cycle, law and AI seem to be approaching a peak:

How can this be a good thing?

Note what happens after the peak and the inevitable trough: “Enlightenment:” The Holy Grail. AI goes from shiny new object to what the Horse Guards leave behind to something truly useful, as they said in the early days of the World Wide Web when someone discovered a site where you could actually do something and not just be forced to stare at mystifying layouts with amateurish lo-res graphics.

But is the hype cycle a law of nature (or, in this case, of economics)? Or is it something we could usefully circumnavigate and just cut to the chase of a maturing technology with genuine commercial application? (An old joke among AI researchers for decades has been that “AI is what we have in the computer science lab; as soon as it actually works, it’s just called software.”)

Whether we could move directly and linearly from “technology trigger” to “enlightenment” strikes me as a question not susceptible to an abstract, a priori answer. So let’s look at the business and economic history of a few other “general purpose technologies,” like AI, shall we?

First was the build-out of the railway system in Great Britain in the 1840’s. A few saliences:

- In 1846 (arguably peak mania), Parliament passed no fewer than 272 laws authorizing new railway companies–more than one every working day of the year. About a third of those entities collapsed before building anything, due to fraudulent or shoddy financing, or acquisition by a competitor.

- Nevertheless, a number of critical trunk routes were built, requiring tremendous reserves of private capital. It’s debatable whether these key routes would have been built anyway, but it’s not debatable that the mania tremendously accelerated their actually getting up and running.

The electrification of industrial production in the United States (assembly lines and factories, that is) in the 1920’s provides another parallel. Although the first commercially successful electric generating station was built on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan in 1882, it took nearly four decades for manufacturing companies to learn how to harness its potential. Well before that happened, however, shares of innumerable highly speculative “electricity” ventures were sold and quickly became worthless.

Initial “electric” factories simply substituted one large electric motor for the typical factory’s one large steam engine, driving an enormous overhead shaft off which numerous belts powered individual and activities. Only in the teens and twenties of the 1900’s did businesses–Ford Motor foremost among them–figure out the real promise of electric-powered factories, namely putting a tremendous number of small electric motors in most places where they could add to productivity.

In the early days of the car industry itself, dozens upon dozens of car makers were created (some estimates put it north of 100), using gasoline, electricity, and steam, but the vast majority failed in their founders’ lifetimes.

On a smaller scale, the relatively recent telecom boom of the 1990’s saw an explosion of fiber optic cable laid across the United States and under the oceans, which stayed “dark” for many years for want of demand.

And to take this cook’s tour back to one of the earliest boom/busts of modernish economic history, the East India Company (chartered in 1600) remains a cautionary tale to this day; but there’s little doubt how powerful it was in accelerating transoceanic trade capability, naval architecture, and such indispensable companion industries as insurance.

So is there a lesson here?

I see full traversal of the “hype cycle” as more or less inevitable. We cannot judge 1840’s railways, electrification, the US auto industry, or the telecom bubble only in hindsight. Truth be told, at the time(s) no one actually knew whether these would be enormous winning bets or impractical capital-sucking quicksand. We had to invest, experiment, and find out. And sometimes that only happens in excess.

So let’s hear it for a bit of hype over AI. We’ll live through this and emerge on the other side better equipped to deliver interesting careers and truly effective, high quality client service. In the meantime…..

One way to look at the “graph” is that it takes some time to develop people who actually know how to use the innovation to generate value. Most of the people who are “polled” in early time will not have the training to understand what the value of the new technology might be or how to use it to good effect. In some sectors – I’d think Law probably is one of them – one may wonder how AI would be used by practitioners. How would a firm develop the bi-directional education that would allow the AI Department to understand how to add value, and the actual lawyers how to participate in the process so that they could not only obtain a report of some sort, but work interactively to provide better and more cost-effective responses to Client?

Mark:

Truly thoughtful, as always; you extend the analysis from the history of “general purpose technologies” to, if I may, the human factor. And I fear, sorry to report, that you have put your finger on a potent cultural/psychological impediment to the rapid or frictionless adoption of AI in Law Land: You note, correctly, that putting it to practical commercial use will require “the AI [gurus]” and the actual lawyers to collaborate. A handful of early-adopter type lawyers surely will, but I fear the vast majority of lawyers will dismiss the AI gurus as dreamy and impractical “non-lawyers.”

The next chapter, of course, is for those same AI gurus to decamp to a FAANG or a plain old corporate that “gets it.”

And (maybe) the next chapter after that is that it will be NewLaw that will optimize the commercial value of AI-empowered legal and in Darwinian market fashion forces the law firms to adapt or else.

Bruce: I agree with all you have written except that the hype cycle “seems to be approaching a peak”. We can quibble over the right metric to make that call, but here’s one: based on the number of AI-related articles found in the fairly consistent set of sources I use for my AI blog (www.MarketIntelligenceLLC.com), the hype still seems to be accelerating. I wonder how much higher it can go before the inevitable decline you describe. Without empirical reason, I boldly predict that we will begin to approach the peak within the next two years. 😉 Mark

Hi Bruce, I like your analysis on AI hype. I’m a researcher in this field and there is definitely hype. When Google recently released a chatbox that allows you to make a reservation at restaurant via Google AI Assistant, it tried to mimic human behavior (like when machine was doing “ahem”, or making sounds that only human can understand) and I found it very dishonest act from Google.. It is simply tweaking a model in NLP. It is not just limited to Google. Most startups that sell themselves as AI startups are shady, if not outright fraudulent. There are many problems within deep learning research communities too. Most deep learning research papers are false (i.e. no independent researchers can reproduce others’ findings… ) and journals like the Nature doesn’t care whether its paper is false (recently, two professors at Harvard University + two researchers at Google AI published a false research paper and it was simply wrong.. but the Nature didn’t do anything.) My personal opinion is that machine learning is going to add values to the society, but moonshot programs like autonomous vehicle are not going to happen within this decade.