In the spirit of reader service, for those of you who might find the summer season has graced you with a bit more leisure time than usual, and on the hunt for a good book, your editor (that would be me) will list and briefly describe what I have been or am reading this summer. With luck something may intrigue you.

I also write with a quaternary or even lower-ranked ulterior motive which I choose at least for now to leave undisclosed. My reasons for this are best explained by analogy to an irreverent friend who when asked the Interview Question that is at once inevitabile, nakedly hostile, and and an invitation to cheerless follow-on (“What’s your greatest weakness?”) responded “That’s for me to know and you to find out.”

I don’t recall whether she really wanted the job, but in my world she should have received an offer without further ado.

In any event, my summer reading list, in arbitrary order.

The Infidel and the Professor, Dennis Rasmussen.

Fabulous recounting of the largely obscure fact that David Hume (the infidel) and Adam Smith (the professor) were best friends from their first meeting in 1746 until Hume’s death in 1776. Obviously, two of the ur characters of the Scottish Enlightenment, and incidentally yet another brick in the wall cementing Adam Smith’s legacy as moral philosopher perhaps even more than brilliant elucidator of capitalism.

Principles, Ray Dalio

Nearly 600 pages that could have been profitably condensed to perhaps one-third that; an intense immersion into the probably polarizing business philosophy behind Bridgewater Associates, an idea meritocracy premised on radical transparency. Recommended far and wide, including by some close colleagues of mine. Salt to taste.

The Last Days of Night, Graham Moore

Historical novel based on actual events in New York starting in 1888 when Paul Cravath, newly out of Columbia Law, took on the representation of George Westinghouse, sued by Thomas Edison over patent rights to the light bulb and the “war of the currents”–DC promoted by Edison (General Electric) and AC promoted, successfully, by Westinghouse. I don’t read historical novels often and never for pluperfect authenticity, but as a survey of a seminal story in American (and global) business history, this is the best in a long time.

The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli is an Italian theoretical physicist with a gift for plain language, and he’s unafraid to lay out what physicists understand about time and what are–invoking this word strictly–profound mysteries. As he says in the preface, “Why do we remember the past and not the future? What does it mean for time to “flow”? Do we exist in time or does time exist in us?” Equations describing many physical phenomena are indifferent whether you run them forward or backward. Whence then does “time’s arrow” come from? I’ll let you know when I’ve figured it out.

The Cost of Discipleship, Dietrich Bonhoeffer

How did one of the leading theologians of the 20th Century come to terms with the horror of the world he was living in? (Capsule Bonhoeffer bio: Born Breslau, 1906; studied in Berlin and New York; left the haven of American to return to Nazi Germany and publicly repudiate the regime; arrested in 1943; hanged in 1945.) How do any of us comprehend extreme sacrifice brought about by ethical consistency? What is one’s obligation in the face of, we can say it, evil? (That Bonhoeffer was Christian is, obviously for me, of personal interest but circumscribes the reach of his writing not one iota.)

Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte

The custom of assigning this to junior high and high school students strikes me as bordering on deranged. Now I can actually appreciate it.

The Code of Putinism, Brian Taylor

Understanding Putin in these times is probably more important in geopolitical terms than understanding anyone else except, well, you know. I’ve always thought it simplistic to assume he’s a revanchist empire re-builder or simply a brilliant KGB-schooled mastermind and brute. I haven’t finished this book yet, but it does make the case that it’s exerting untoward weight abroad while sowing misrule domestically.

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire:A 500-Year History, Kurt Andersen

Very much, as they like to say elsewhere, “what it says on the tin.” How did America get to where it is today, when everyone seems entitled not only to their own opinion but, disorientingly, to their own facts as well? Andersen starts with Puritans, proceeds through everything in the interim through Salem witches, “know-nothing’s,” PT Barnum, Area 51, to the 1960’s, Esalen, Scientology, to today, GMO’s and vaccines, creation science, “truthiness,” and all the rest of it. As Andersen puts it early on, “being American means we can believe any damn thing we want [and] our beliefs are equal or superior to anyone else’s, experts be damned.”

In the chilling final chapter, he quotes an early 20th Century observer of a comparable scene: “A mixture of gullibility and cynicism have been an outstanding characteristic of [our population]. In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true…ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie anyhow.”

The writer? Hannah Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism (1951).

What Would the Great Economists Do?, Linda Yueh

Not actually “what it says on the tin,” and better for it. The beguiling premise of Yueh (a talented writer) here is to devote a chapter to each of 12 great economists and their projected/plausible views on contemporary issues. Among them are Adam Smith (otherwise I wouldn’t be reading the book), David Ricardo, Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, Joseph Schumpeter, and Milton Friedman. But the structure around contemporary issues–trade and tariffs, globalization or Brexit, the future of the Chinese economy– is more pretextual than real. The book actually constitutes capsule biographies of the dozen luminaries plus condensed explanations of their intellectual views and theories. .

In fairness, probably for the harder-core students of economics in the audience, but a delightful survey course and refresher to yours truly.

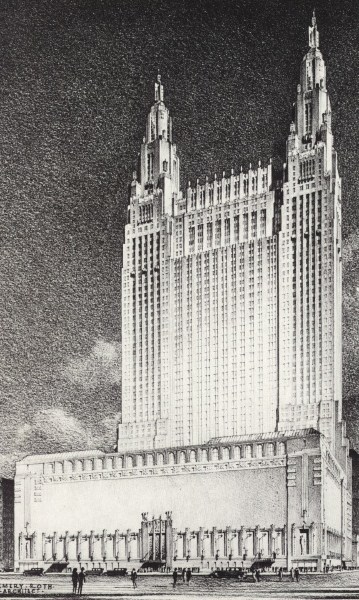

Never Built New York, Greg Goldin et al.

Coffee table book. Nearly 200 proposals covering two centuries: Bridges, skyscrapers, parks, airports, master plans, transit proposals, and more. Blessedly little “Jetsons” style elevated roadways and pedestrian malls, but who knew Buckminster Fuller ever proposed a geodesic dome for Dodger Stadium in Brooklyn? OK, something of an indulgence for a besotted New Yorker, but it’s summer after all.

Happy reading!