Yes, I did mention that Summers/Blanchard IMF paper. Without going into the log-extrapolated statistical details, here are the “main takeaways,” as the authors put it (see pg. 17 of the paper I cited above):

- Two thirds of recessions are followed by lower output vis-a-vis the pre-recession trend.

- Almost half are also followed by lower output growth vs. pre-recession.

- Recessions caused by shocks (supply shocks and financial crises) are even more likely to be followed by output shortfalls, implying that the shocks help explain the recession itself as well as subsequent lower output.

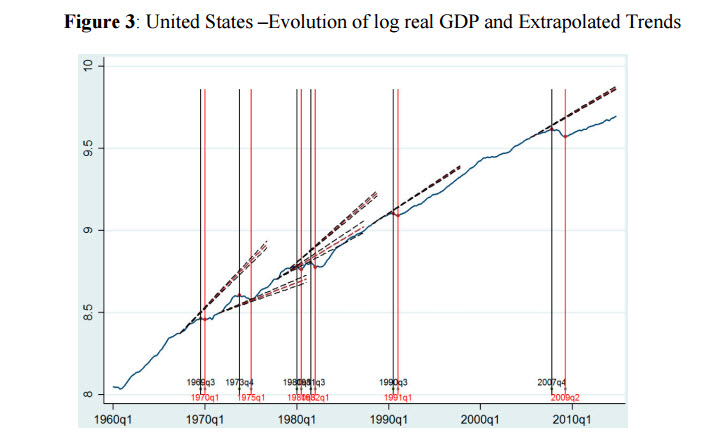

To complete the visuals for this tour of the latest sobering economic analysis, here’s the most visually compelling chart from the IMF paper. You don’t need to know precisely how each data series was calculated to get the gist.

From 1960 to today, recessions (vertical lines) cause subsequent real output (the solid blue line) to fall below pre-recession extrapolated straight line output (the dotted black lines). And this past Great Recession saw the greatest decrease in the slope of the post-recession output line of all. (The geeks in the audience will be happy to explain how that’s reflected in terms of the second derivative, but for the civilians the message, as we’ve written before, is that this was a really bad recession.)

Back to Law Land, shall we? So what does this mean for you? A few thoughts:

- In the long run, law firms cannot grow faster than our clients.

- You may have heard of a book published a few years ago on this topic titled Growth Is Dead: Now What? May I submit that we have positive confirmation of that hypothesis and that our attention has to turn now, if it hasn’t already, to the “Now What?” part of the title.

- I’ve argued before that we’re in a battle for market share. We’re in a battle for market share.

- You can speculate—I’ve heard the arguments and actually tend to concur—that in straitened times corporations will become more discriminating about whether they pursue litigation and the scale at which they wage litigation war if they do. We’ve already seen evidence of this in the declining share of litigation vs. transactional work across the Thomson Reuters PeerMonitor database of firms. It would be logical to believe this trend will stay constant or accelerate.

Finally: The market for “law firms” is a subset of the market for legal services. Not only are firms facing a battle for market share with other law firms, you’re now competing with non-law firms.

This all has implications for your long-term strategic planning, meaning, in the Cliffs’ Notes version, (a) what practice areas you focus on and (b) where you perform them (the geographic footprint of your offices).

Among today’s increasingly sophisticated, choosy, and discerning clients, the gravest mistake you can make is to have your firm be a full service, general practice, not-elite and not-economical, destination for nothing in particular. Be a destination for something. Stake a claim to a calling-card practice and stick to it. Does this mean making choices, and saying no to some things? Well, it’s called strategy for a reason.

If you doubt me, you might want to add a dose of business/financial/economic reporting to your daily media feed. Or invest in a business intelligence analyst.

You’re doing those things already, right?

Not a shock that Summers and the others of his ilk don’t mention the Fed’s ridiculously distortive 8 year zero interest rate policy, which drastically exacerbates reckless risk-taking and reduces incentive to make capital investment, hence the exorbitant amount of share buybacks that have been going on for many years. Law firms will feel this future dent in growth more painfully because law is still seen as a cost and not a benefit, as you notice litigation is feel it now already.

Dear Bruce,

Thanks again for a thoughtful piece; as citizens we all should be paying attention to these matters. I appreciated your citation to Growth Is Dead, and I also thought about the analytical framework you proposed in your “New Taxonomy.” In particular, is it perhaps appropriate, as people think about the economic information, to wonder about what the level of aggregation is that is economically most important for one’s own firm and its peer/competitors? For example, are GDP and national employment statistics the right data set to be evaluating if one’s firm is part of the King of the Hill group? Necessary, perhaps, for context, but perhaps not sufficient? Or how would one extend the sort of analysis you have put forward to the situation for the Global Players? That is, when you ask if we are studying and analyzing economic data (in my business we do), is our task probably not to be sure we match the purposes and objectives of our specific business situation(s) to the appropriate scales and loci of the information we will need to understand?

Dear Mark:

Thoughtful as always. You spoil us.

You are absolutely correct to point out that the lens one should employ in terms of providing the appropriate context for their firm is a function of the firm’s footprint–metropolitan area, regional, national, or global. This may be most vividly true for King of the Hill firms, where (as I alluded to in Taxonomy), the prospects for your firm in 2016 are very different depending on how astutely one’s forebears selected their “Hill!” Detroit and Rochester, NY produced one sort of outcome, whereas Austin or Phoenix produced a different sort.

I thought, when composing this piece, of extending the analysis to include the EU, China/India, and Japan, but prudence (and the desire to actually see it published) triumphed.

The last thought I have along these lines is that “integrated focus” firms, to the extent they align themselves with client-industries, need to select their turf with at least as much foresight as the “King’s.”