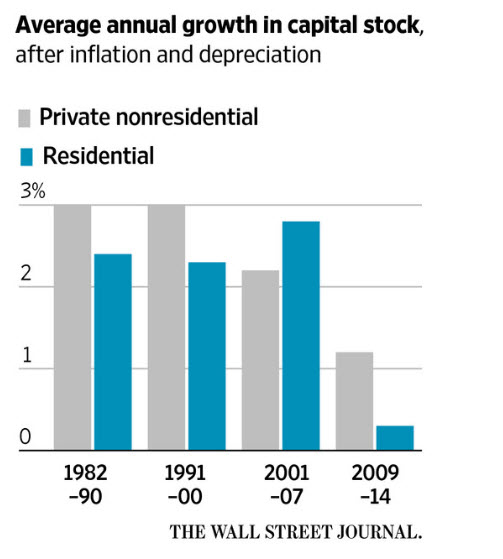

Going back all the way to the post-dotcom meltdown, the “capital investment shutoff” thesis posits that most of the productivity gains from IT were in place by the early 2000s. Throwing more new hardware and software at workers didn’t generate the same bang for the buck, so businesses naturally dialed it back. Something was clearly going on here: The annual growth of business capital investment (net of inflation and depreciation) slowed from 3% to 2.2% from the 1990s to the 2000s.

Since the Great Meltdown (let’s date it to 2009), even though interest rates are at historic lows, business capital investment has fallen by almost half, to a mere 1.2% per year. Take a look for yourself:

Now we cross over into vicious circle territory:

- Lower business capital investment

- Makes productivity growth even more sluggish

- Leading to slower income growth

- Cutting consumer spending

- And discouraging businesses from investing even more.

Once this set of expectations gets baked in to how people anticipate the world will continue to work, it’s even harder to dig out.

Well, that’s not 100% true. As Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, explains in his new book The End of Alchemy (I’m relying on reviews here since I haven’t read it yet), if income is insufficient to support a family or a firm’s desired spending level, you can always…borrow! Eddie George, King’s predecessor at the BoE, even said in 2002, “unbalanced growth…is better than no growth.” Lords of Finance, indeed. But that’s exactly what central banks were encouraging people to do. This all hit a wall when households and firms came face to face with the degree of leverage they’d put onto their balance sheets, and of course opaque and even fraudulent loan terms, and an incomprehensibly rickety shadow banking system made matters far worse.

Getting back to today: Theoretically, there’s nothing wrong with the US economy that a little healthy labor market growth wouldn’t solve—in particular, by enticing more of those potentially productive workers who have dropped out of the labor force entirely back into the ranks of productive workers.

Maybe we shouldn’t be holding our breath on this one, however.

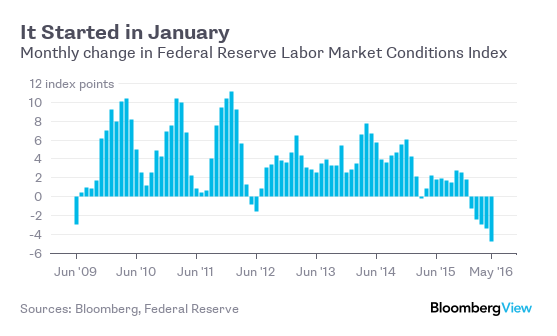

A couple of years ago Fed economists dreamed up a new data series composed of 19 different labor market indicators and named it the “Labor Market Conditions Index.” (I don’t blame them; our historic measures all have deep intrinsic flaws.) They were able to extrapolate it backwards to 1976 and the intrepid Justin Fox of Bloomberg View was courteous enough to publish the series back to the official end of the Great Recession in June 2009. Here it is:

This shows it down 5 months in a row, at an accelerating rate, its worst showing since the end of the last official recession. Worse, two of the LMCI’s more important leading components, labor force participation and temporary worker demand, are also down markedly in the last half year.

Not a shock that Summers and the others of his ilk don’t mention the Fed’s ridiculously distortive 8 year zero interest rate policy, which drastically exacerbates reckless risk-taking and reduces incentive to make capital investment, hence the exorbitant amount of share buybacks that have been going on for many years. Law firms will feel this future dent in growth more painfully because law is still seen as a cost and not a benefit, as you notice litigation is feel it now already.

Dear Bruce,

Thanks again for a thoughtful piece; as citizens we all should be paying attention to these matters. I appreciated your citation to Growth Is Dead, and I also thought about the analytical framework you proposed in your “New Taxonomy.” In particular, is it perhaps appropriate, as people think about the economic information, to wonder about what the level of aggregation is that is economically most important for one’s own firm and its peer/competitors? For example, are GDP and national employment statistics the right data set to be evaluating if one’s firm is part of the King of the Hill group? Necessary, perhaps, for context, but perhaps not sufficient? Or how would one extend the sort of analysis you have put forward to the situation for the Global Players? That is, when you ask if we are studying and analyzing economic data (in my business we do), is our task probably not to be sure we match the purposes and objectives of our specific business situation(s) to the appropriate scales and loci of the information we will need to understand?

Dear Mark:

Thoughtful as always. You spoil us.

You are absolutely correct to point out that the lens one should employ in terms of providing the appropriate context for their firm is a function of the firm’s footprint–metropolitan area, regional, national, or global. This may be most vividly true for King of the Hill firms, where (as I alluded to in Taxonomy), the prospects for your firm in 2016 are very different depending on how astutely one’s forebears selected their “Hill!” Detroit and Rochester, NY produced one sort of outcome, whereas Austin or Phoenix produced a different sort.

I thought, when composing this piece, of extending the analysis to include the EU, China/India, and Japan, but prudence (and the desire to actually see it published) triumphed.

The last thought I have along these lines is that “integrated focus” firms, to the extent they align themselves with client-industries, need to select their turf with at least as much foresight as the “King’s.”