“Something looks wrong.”

So begins Greg Ip’s most recent column in The Wall Street Journal.

What exactly “looks wrong?”

Well, the economy, stupid.

Specifically, as Ip points out, consumer spending has been rising strongly recently but business investment has been headed down for two straight quarters, which is supposed to happen only in recessions. (Ip is the Journal’s chief economics commentator, a post he’s held for about a year after being at The Economist for over a decade. Before that he was at the Journal for his first tour of duty, which lasted 8 years.)

Ip is hardly alone.

If you follow the business/financial/economics press as I do, you’ll have heard an increasing volume and intensity of commentary and analysis over the last, say, six to nine months, dwelling on themes such as:

- “secular stagnation” (more below)

- lagging productivity growth

- the exhaustion, and exhaustion, and exhaustion, of monetary policy

- accompanied by partisan political paralysis on fiscal policy

- declining labor force participation

- the threat of robots/automation/AI, in the nearish term, to unskilled and semiskilled workers

- stagnation in middle class standards of living

- zero real growth in household incomes

- and I could go on.

Obviously none of these are happy themes, but separately and together they reinforce the conviction that the economy isn’t responding to this post-recession period as it typically has in the wake of past recessions. Ip worries that our disappointing economic growth is worse than a hangover from the Great Recession and that it’s “part of a deeper malaise that predates, and indeed may have helped cause, the financial crisis.”

Evidence isn’t hard to find:

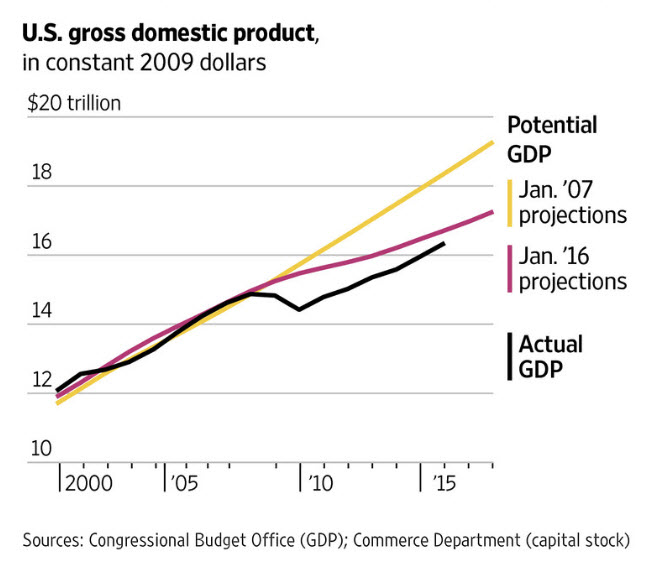

- From 1980—2007, annual economic growth averaged 3% in the US; since then the average is 1.2%. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the overall US economy is 11% smaller than where they thought it could and should be by now.

- Productivity growth has barely kept its head above zero in recent years: At +0.5%, it’s the lowest it’s been in decades. There’s no sign of its picking up.

- The historically unprecedented duration of exremely low interest rates “could lead to excessive risk taking and over time to unsustainably high asset prices and credit growth.” (Yes, folks, we’ve seen this movie before, in the housing bubble.)

This chart illustrates projected vs. actual GDP growth:

As I mentioned, Ip is far from alone in his thesis, and it’s buttressed by an IMF Working Paper recently published by Larry Summers (of Harvard fame), Olivier Blanchard (the IMF’s former chief economist), and Eugenio Cerutti (IMF), whose abstract begins as follows:

We explore two issues triggered by the crisis. First, in most advanced countries, output remains far below the pre-recession trend, suggesting hysteresis. Second, while inflation has decreased, it has decreased less than anticipated, suggesting a breakdown of the relation between inflation and activity. To examine the first, we look at 122 recessions over the past 50 years in 23 countries. We find that a high proportion of them have been followed by lower output or even lower growth.

We clearly seem to be in the “high proportion” of recessions (their paper calculates the number as about 70%) that turn into long-run drags on growth. Why?

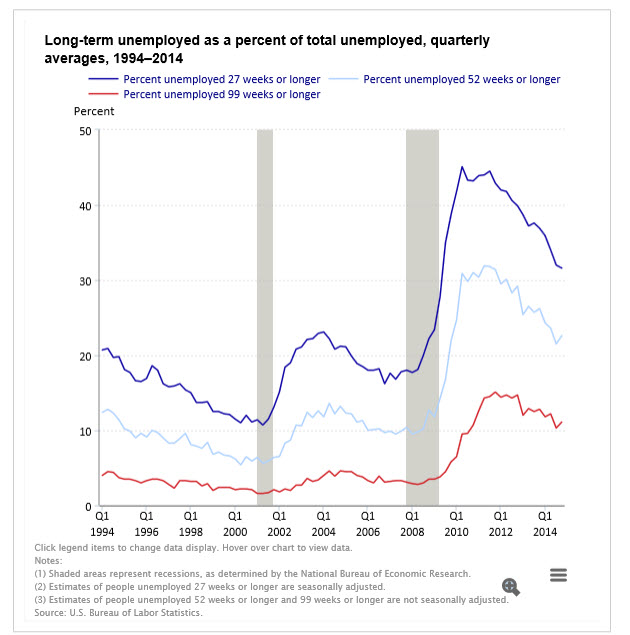

The leading explanation is that the Great Meltdown caused such severe long-term unemployment that discourged workers dropped out of the labor force entirely, decreasing the US’ productive labor capacity. (The BLS draws the official line between “short–term” and “long-term” unemployment at six months, which is necessarily a somewhat arbitrary choice but perfectly rational.) It reached “historically high levels” in the wake of the Great Meltdown, as evidenced by this utterly depressing chart:

Meanwhile, on the capital front, businesses slashed investment because they were shut out of the borrowing markets, they had lost all faith in a prosperous future (no “animal spirits”), or onerous new regulations imposed new and higher costs and generally threw sand in the gears. Of course, if you have fewer available workers and you arm them with less capital equipment, no one should be surprised if output and productivity are impaired.

It gets worse.

Not a shock that Summers and the others of his ilk don’t mention the Fed’s ridiculously distortive 8 year zero interest rate policy, which drastically exacerbates reckless risk-taking and reduces incentive to make capital investment, hence the exorbitant amount of share buybacks that have been going on for many years. Law firms will feel this future dent in growth more painfully because law is still seen as a cost and not a benefit, as you notice litigation is feel it now already.

Dear Bruce,

Thanks again for a thoughtful piece; as citizens we all should be paying attention to these matters. I appreciated your citation to Growth Is Dead, and I also thought about the analytical framework you proposed in your “New Taxonomy.” In particular, is it perhaps appropriate, as people think about the economic information, to wonder about what the level of aggregation is that is economically most important for one’s own firm and its peer/competitors? For example, are GDP and national employment statistics the right data set to be evaluating if one’s firm is part of the King of the Hill group? Necessary, perhaps, for context, but perhaps not sufficient? Or how would one extend the sort of analysis you have put forward to the situation for the Global Players? That is, when you ask if we are studying and analyzing economic data (in my business we do), is our task probably not to be sure we match the purposes and objectives of our specific business situation(s) to the appropriate scales and loci of the information we will need to understand?

Dear Mark:

Thoughtful as always. You spoil us.

You are absolutely correct to point out that the lens one should employ in terms of providing the appropriate context for their firm is a function of the firm’s footprint–metropolitan area, regional, national, or global. This may be most vividly true for King of the Hill firms, where (as I alluded to in Taxonomy), the prospects for your firm in 2016 are very different depending on how astutely one’s forebears selected their “Hill!” Detroit and Rochester, NY produced one sort of outcome, whereas Austin or Phoenix produced a different sort.

I thought, when composing this piece, of extending the analysis to include the EU, China/India, and Japan, but prudence (and the desire to actually see it published) triumphed.

The last thought I have along these lines is that “integrated focus” firms, to the extent they align themselves with client-industries, need to select their turf with at least as much foresight as the “King’s.”