Well, it all matters, after a fashion, which is why I’ve put this together, but there are two metrics in particular that I think have longer-term consequences for competitive positioning. They are Revenue per Lawyer, or RPL, and Profit Margin.

RPL matters as a very rough and ready reflection of how highly clients value what you do: What will they pay to rent one of your lawyers for a year? (Not partners, not associates, simply the “average” lawyer at your firm.)

Profit Margin matters because, well, the more you have the more you can do. As food and ammunition are to an army, profits are to law firms. Profit is a weapon you can wield as you choose.

So let’s look at two final charts putting these figures on display.

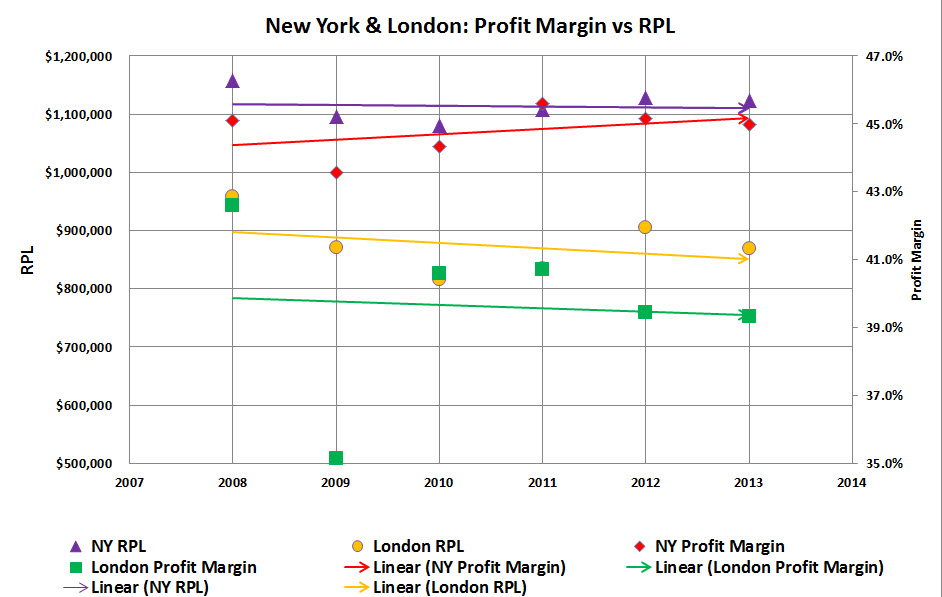

First we have the profit margins vs. the RPL of New York and London firms over the six years we’ve been studying:

The trend lines [“Linear (London Profit Margin),” etc.] are best-fit linear trend lines for each of the four data series. The markers are the absolute values for each city for each year, with RPL on the left vertical axis and profit margin on the right vertical.

What do you see just eyeballing it?

I see two rather consistent features: New York’s RPL and profit margins are higher than London’s, and New York’s are flat or trending slightly up while London’s are sliding.

Now, let me hasten to add, for those of you desiring an emergency refresher in Statistics 101, that scales matter and you would be well advised to look carefully at the vertical axes before drawing your own conclusions about whether these real differences are material.

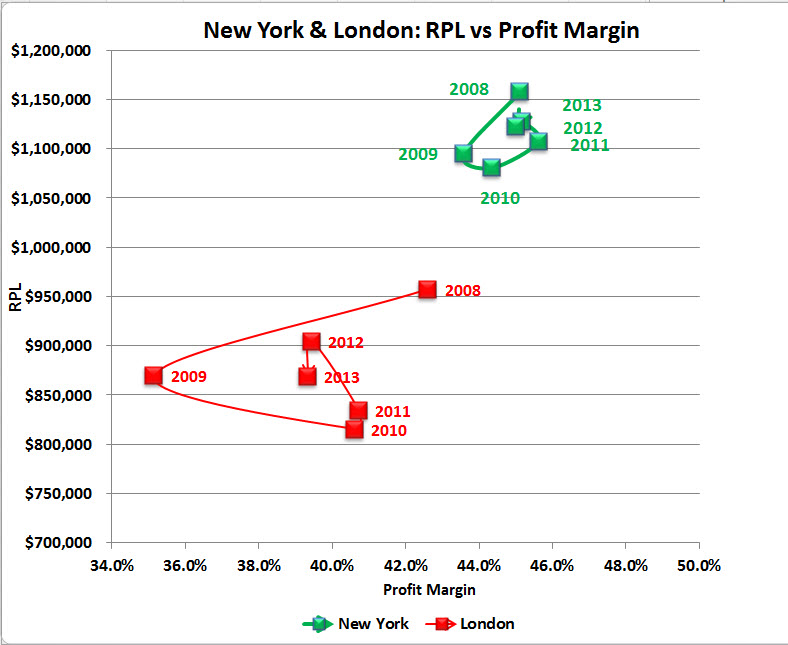

Finally, let’s redraw the same data into a scatterplot of NY vs. London and RPL vs. profit margins, by year. Voila:

The differences are, I submit, more pronouncedly evident in this rendering of the data.

- New York is above and to the right of London for the entire period

- London displays more volatility (although it represents four firms to New York’s six), and

- While the gross trends over the six year period were the same in both cities—2008 very good, 2009 much much more, and 2010—2013 a slow incremental recovery—New York is closer to making up the lost ground than London.

What does this all mean? That merely depends on how you see global capitalism and finance evolving over the next couple of decades. And if you can see that clearly and unerringly, are you sure you shouldn’t be working for the NSA or MI6?

To oversimplify:

(1) If you think the rise of the East and the South will continue or accelerate, and accordingly that London and New York will matter relatively less in 2020 or 2030 than they do today, then Allen & Overy and Clifford Chance are “right” and any firms with 95% of their lawyers in one zipcode or time-zone may need to perform a midcourse correction lest history leave them behind.

(2) Alternatively, if you think the United States will be the world’s only superpower for as far as the eye can see, with New York its indisputable financial and intellectual capital, and UK-rooted Anglo-Saxon common law the lingua franca of international commerce, then Allen & Overy and Clifford Chance are “wrong” and may need to pivot.

And I suppose if you think the Visigoths of disruption are marching relentlessly on the Citadel of BigLaw, in serried columns from the north, then this entire essay has been a quaint exercise in nostalgia.

The morals here are at least two: First, it is not mere anecdote or urban legend that New York’s elite and London’s Magic Circle are embarked on different strategies; the data shows it to be true. And second, at the highest level of generalization, those different strategies reflect different world-views. The differences stem not from perversity or blindness or provincialism, but from profound differences of opinion in where global commerce is going and how the world’s globally elite law firms should configure themselves to remain on top.

And a third moral: Visigoths or no Visigoths, the only serious mortal threat any of these firms could face will arise within themselves—through complacency, self-satisfaction, short-termism, or a surrender to greed.

What do you think this lineup will look like in 2020?

Very interesting – thank you!

Do you think that the figures are (heavily) impacted by currency fluctuations between 2008 and 2013?

You’re welcome!

The short answer, to my mind, about currency fluctuations is:

My bottom line is: Can’t do anything about them, so let’s ignore them.

How do the numbers differentiate (or do they) between compensation paid to equity partners as profit v. salary treated as an expense? Is everything paid to an equity partner treated as profit?

On a less serious note, any post that references Warner Wolf is ++ in my book. Now if you can somehow work in a reference to Jerry Girard we’d really be talking.

Unfortunately you’ve completely ignored the fact that the pound –the billing currency of the lion’s share of magic circle ops — was at multidecade highs of over $2:£1 in 2008, then fell back by about 25%, with high volatility (like all financial markets!). This by itself accounts for most of the trend in several of the charts you put forth which measure performance in dollars. Of course New York looks less volatile when you measure things in US currency! Of course the Magic Circle declines during years when GBP declines! It’s a shame you didn’t think to address this variable since it is a far more significant determinant than any of the theories you put forth in your article.

I actually used each year’s average GBP/USD exchange rate for that year, as opposed to one average over the entire period. That’s the methodology.

As for the substance of your observations, let us stipulate that the currency movements you posit are correct. What, then, is one to do in terms of analysis? I don’t think the managing partners of any of the firms identified in the piece would suggest they be ignored, or can be ignored in real life when it comes to partner compensation time. At the risk of being simplistic, yes indeed currencies fluctuate. It strikes me as a hard fact on the ground that one simply has to build into any crossborder analysis of this sort. I don’t see any alternative route.

You finish this with the question “What do you think this lineup will look like in 2020?” Might now be a suitable time to revisit?

In ordinary days, you would not be wrong, but given what’s going on in the world this year I think it only prudent to table this until we emerge on the other side, either via universal vaccine or brute-force herd immunity, which some elected leaders seem to be pursuing in deed if not in word.