But in one of the first data-driven forays beyond the chorus of keening that usually begins and ends these discussions, Above the Law took the top 50 AmLaw firms and calculated the compound annual growth rate of their revenue per lawyer over the 2009—2013 period. They wanted to attack the question posed in the title of their article, “Is there a business case” for greater female representation in the ranks of partners?

Why CAGR of RPL? I would argue, as they apparently believe, that it’s about as “clean” a number as one can get out of the publicly available data, in that it’s hard to fudge top-line revenue and it’s hard to fudge lawyer headcount. RPL is also a very rough proxy for clients’ perception of quality, as it measures what clients are willing to pay to rent one of your lawyers for a year. And CAGR has long been my King of the Hill metric in terms of showing strength and sustainability of trends over time.

Here are some of the highlights of the RPL/CAGR calculation. Then on to how it correlates (or doesn’t) with proportion of female partners.

- The CAGR figures ranged from -11% to +11%, with a median of +3.1% and an average of +2.8%.

- Three of the six worst-performing firms on the CAGR metric are vereins: Dentons and DLA in spots ##1 and 2 respectively, and Hogan Lovells #6. Numbers 3, 4, and 5 respectively are Wachtell, Covington, and K&L Gates, which as far as I can tell have no more in common than ten-penny nails, a Picasso, and Niagara Falls.

That means firm-specific issues must have placed them here, and since a license to publish is a license to speculate, here are my thoughts on those three: Wachtell is all deals all the time, and deal flow was pitifully low during the timeframe at issue. Covington may have suffered a bit of the Patton Boggs “earmark disease.” Because earmarks essentially disappeared under Congressional reform provisions, clients seeking earmarks–couldn’t. So much for an entire line of business. As for K&L, the timeframe coincides with their mergers in intrinsically lower RPL geographies including the Carolinas, Texas (outside Houston), and Australia, and their expansion into more low-RPL areas (Poland, Russia, Qatar, and the UAE).

Such are my theories, anyway. - The ten best-performing firms by CAGR were Quinn Emanuel #1 at +11%, Kirkland #2 at 9%, and (in order from #3 to #10): Alston, Cooley, Goodwin Procter, Simpson Thacher, Cravath, Skadden, Gibson Dunn, and Debevoise. With the somewhat questionable presence of Alston and Cooley in this crowd, they’re all hands-down top-drawer outfits whose presence at the top of the food chain reflects, well, their presence at the top of the food chain.

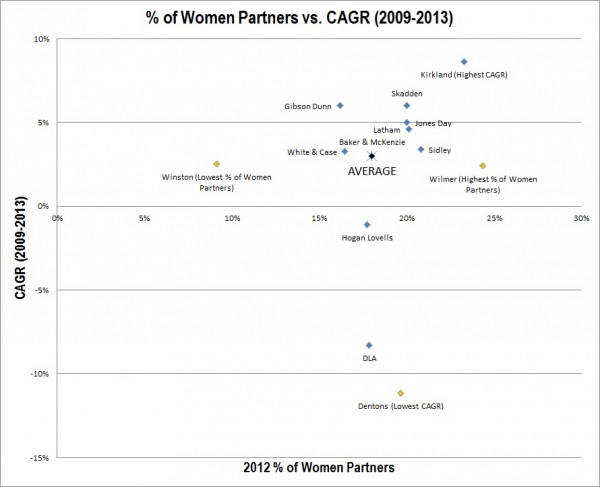

Now here’s where it gets interesting. Here’s the scatter-plot from ATL of CAGR/RPL vs. percentage of female equity partners. I also ran a regression analysis on it (see below).

The correlation coefficient I derived from this dataset is 0.00962. In other words, after all that work, we can only conclude that there is no meaningful correlation. For those of you who prefer anecdote to data, I’d be happy to have a word with you after class, the firm with the lowest percentage of female partners (9%—Winston) had an RPL/CAGR of 2.53% and the firm with the highest female percentage (24%—WilmerHale) had an RPL/CAGR of….2.42%.

My initial reaction was that this had been the ultimate exercise in Good News/Bad News. Across the industry—always realizing your firm’s mileage may vary—having more, or fewer, female partners doesn’t help a firm’s financial performance but it doesn’t hurt it either. Having more, or fewer, male partners doesn’t help a firm’s financial performance but doesn’t hurt it either. A big fat so-what, then?

Not quite.

Let’s combine that NAWL chart with the work of Gary Becker (who, sadly, died just a few months ago), a University of Chicago Pprofessor who won the 1992 Economics Nobel “for his work in extending microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behavior and interaction, including nonmarket behavior” (in the words of the award). This was actually not such abstruse stuff. It’s worth a brief rehearsal of what Becker contributed, but it’s the last item on the list that’s of particular interest to us today. His work encompassed:

- The value of investments in human capaital, and specifically the return on education and training.

- His theory of the economic functions of the family (which he analogized to a “small factory”) which covered, catholically, everything from what families “produce” (meals, shelter, entertainment, etc.) but also how income affects preferences for education, child care, labor force participation, and even fertility.

- Crime and punishment, where he theorized that—with the exception of psychotic and mentally disturbed behavior—many criminals were rational economic actors behaving under conditions of uncertainty.

- And finally, to our topic du jour, economic discrimination. Here’s the core of Becker’s work in this area (from the University of Chicago site, emphasis mine):

Another example of Becker’s unconventional application of the theory of rational, optimizing behavior is his analysis of discrimination on the basis of race, sex, etc. This was Becker’s first significant research contribution, published in his book entitled, The Economics of Discrimination, 1957. Discrimination is defined as a situation where an economic agent is prepared to incur a cost in order to refrain from an economic transaction, or from entering into an economic contract, with someone who is characterized by traits other than his/her own with respect to race or sex.

Becker demonstrates that such behavior, in purely analytical terms, acts as a “tax wedge” between social and private economic rates of return. The explanation is that the discriminating agent behaves as if the price of the good or service purchased from the discriminated agent were higher than the price actually paid, and the selling price to the discriminated agent is lower than the price actually obtained. Discrimination thus tends to be economically detrimental not only to those who are discriminated against, but also to those who practice discrimination.

Before proceeding, a caveat from the publisher here (that would be me): This is a column focused on economic analysis. Do not confuse it with either a column describing what the world should or ought to look like, nor with a column attempting to justify the intentions and motivations of those responsible for the way the world actually is. (I’ve never met the vast majority of them and neither have you.) Finally and perhaps most importantly, the fact—I take it as fact—that workplace discrimination is lousy for your business is utterly different than thinking that because it’s irrational it cannot or does not exist. Both I and the late Prof. Becker would resoundingly confirm that people engage in irrational behavior all the time. This is, as they say, an economic and not a descriptive or normative analysis.

Two thoughts:

1) If there are equally qualified women and men, in equal proportions, then wouldn’t it be the case that by going deeper into the pool of men than women to promote partners, firms are getting somewhat less qualified men than the women they could have had? Now, of course, there are many characteristics that determine qualification, and perhaps the differences are insufficient to translate into large differences in money, but all things being equal, it seems that some women don’t make partner despite being more qualified than the men who do. If you look at the chart, with Wilmer having the most female partners, it’s still nowhere near 50%. Would you expect a tipping point at some percentage of women partners that produces larger changes, as opposed to a linear relationship?

2) Your conclusions about what hold women back are common, but by no means the whole story, and in my experience aren’t necessarily the most prevalent or important issues. For example, men are judged on their potential while women are judged on what they have done. When it comes to rainmaking ability for partnership decisions, men have an edge if all they need is potential. Women are expected to prove themselves over and over while men only need do so once, which is frustrating to the women. A “go-getter” attitude is appreciated in younger associates, but by the time women are at their 5th or 6th year, that attitude is considered aggressive, sharp-elbowed, and the sign of someone who is not a team player. Women are taken off cases when they become pregnant and have trouble getting work when they return from leave, which I have heard male partners say is because those women will probably just stay home with the kid anyway. But the result is they can’t meet their hours and thus won’t get bonuses or promotions. Even in this day and age, sexual harassment is rampant and plenty firms work to quell the outcry rather than address the problem.

The solution, of course, is to have women partners who are viewed as supremely competent, because then no one will question that women can do all the things men can do.