Linear extrapolations are widely suspected of being unreliable, but maybe not widely enough. Stated differently, it’s a category error to engage in static, not dynamic, analysis.

Stated yet differently, the interesting challenge is almost never to ask, “What can we do to solve this problem?” but instead, “What happens after we take this approach to solving the problem?”

Let me give you a couple of specific examples.

A long-running contributor to structural disequilibrium in the metropolitan New York traffic congestion pattern is that bridges across the East River are toll-free whereas almost all other bridges and tunnels in the area carry tolls as high as $12 one-way. Not surprisingly, the East River bridges are chronically congested and “over capacity.” (The experts’ knowing diagnosis that they’re “over capacity” always amuses me; drivers are paying in time, not money: The “capacity” of the bridges is what it always has been.) So periodically proposals are floated to impose tolls on these bridges, with seemingly reliable projections of how much revenue would be collected based on today’s vehicle traffic multiplied by the average toll.

This is a linear extrapolation, a static analysis, and it’s wrong. It overlooks the question, “How will people alter their behavior in light of the tolls?” Obviously, the answer is that some will carpool, some will take mass transit, some telecommute more often, others use different combinations of bridges and tunnels. Whatever happens, toll revenue will fall short of {[today’s traffic volume] x [proposed toll]}.

Now, in our own backyard, we have a stunning example of market dynamics at work.

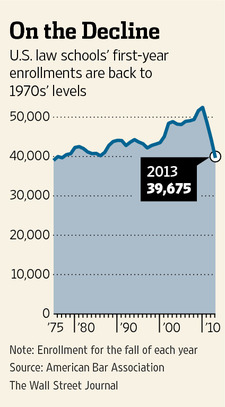

The Wall Street Journal reports “First-Year Law School Enrollment at 1977 Levels,” and here are the numbers:

- the number of 1L’s fell 11% this year, down nearly 5,000 from 2012, at 39,675 students

- 1977’s number was precisely one more, 39,676

- 1975 was the previous low, at 39,038

- in 1975 there were 163 ABA-approved law schools; today there are 202

The all-time high of 1L enrollments was three short years ago, in 2010, at over 52,000, about 30% above this year’s number. Here it is graphically:

Meanwhile, The National Law Journal’s story on this quotes University of St. Thomas School of Law professor Jerome Organ writing in an evidently off-handed fashion, without comment or analysis, that “most law schools see further declines in their LSAT and GPA profiles.” This isn’t the first time we’ve heard this—that the decline in applicants/enrollees has been especially high among the more academically qualified students—but it certainly begs for an explanation. My hypothesis, divorced from empirical basis at this point, is that the brighter students have more options. But not to cast aspersions.

There’s more: In recent years, average graduating class size (3L’s, that is, and to state the obvious there’s shrinkage between 1L and 3L numbers) has been about 44,000. We’re now over 10% short of the number of students law schools have been graduating recently. This means that, for all practical purposes, law schools below the elite tier have become open enrollment.

But back to dynamic markets.

Admirable and swift has been the reaction of prospective law students to the changed legal marketplace since 2008—2010. Some people may not like what has happened, and many more may be completely baffled about how to respond, but this is the way markets are supposed to behave. Econ 101: When demand drops, supply should follow. As the WSJ drily puts it, “those considering legal careers appear to be paying attention.”

All the evidence so far, however, is that law schools are really not—or they’re not acting on what they’re seeing. If you beg to differ, I ask you merely to read on.

This raises a host of questions about the business models for law schools going forward—especially standalone, independent law schools—as the always reliable Bill Henderson points out with understatement:

“It is a big drop-off,” said William Henderson, a professor at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law who has written extensively on the legal profession. “The wind has been at our backs for many, many decades, and we haven’t really had to operate like a lot of businesses, with adjusting to swings in demand.”

And according to Barry Currier, identified as “the ABA’s managing director of accreditation and legal education,” law schools have no intention of behaving like businesses. Even though two-thirds of the 202 ABA-accredited law schools reported declines in 1L enrollment, with 60% of them suffering declines over 10% (the ABA promises to name names later).

This gets even richer: Currier seemingly takes schools to task for “[presuming] that the market for law school graduates was growing, [but they shouldn’t have expected] those numbers were going to be sustainable for a long time.” Fair enough, one supposes, had the schools accepted this cold dose of reality and stopped there. But incredibly, Currier goes on to report many schools are still in a state of complete denial: Shockingly, 27 law schools expanded their 1L clases by 10% or more. How is that possible? “Some schools may have corrected and are now in a position to increase their enrollment.”

May we stipulate:

- that financial reality is going to dictate that many schools have to redesign their business?

- that this is a “correction” that will be in place for the foreseeable future?

- and that law schools cannot magically gin up demand for 1L enrollees single-handedly, in the teeth of economic and technological changes that argue that we’ve moved to a new and lower “set point” for new-JD demand?

Note to those running law schools: You will find it bracing indeed when the market decides it wants to buy a lot less of what you’ve been selling.

If law schools come to grips with all those new realities, then the most obvious challenge is simply whether law schools caught in the wrong place in this game of enrollee musical-chairs can react in a sufficiently meaningful and rapid way to the downshift in demand to even survive.

They have large and long-term fixed costs not just in the form of real estate and facilities, which presumably have some non-zero value in alternative uses, but, most glaringly, tenured faculty, which is not an “asset” for which there is a market at all. And even if there were a market for this asset, it doesn’t belong to the school in the first place and isn’t the school’s to sell.

Putting this all together, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that some law schools are going to close their doors. I actually have a request for those who would differ with this conclusion, since I think the past few years have shifted the burden of proof onto you. Please explain, in the comments, why all law schools will—and deserve to—remain in business.

If you’re running a law firm and think that firms are challenged in terms of adapting their business model, count your blessings that you’re not one of the less fortunate law schools. Welcome to dynamic markets.

paradox is that we need better lawyers and law schools than ever (but not as many attorneys); problem of law schools is a lack of faculty skills induced by tenure; most faculties simply do not have the skills to teach what we need lawyers to be able to do

It will be very pivotal for the legal education market in February when the decisions are made regarding the Task Force’s recommendations. Significant deregulation is needed, but I highly suspect that the committee will remain very conservative and not adopt the necessary liberalization of the regulations, even in light of the declines in applications.

The State Bar associations and other Bar Associations seem remarkably quiet on this issue. They have a much greater incentive to turn around this decline than the ABA does yet we here very little, if any, response from them. They will pay the price in years to come as declines in bar fees and other fundraiser initiatives come as a result of a decline in lawyers. If the ABA does not deliver on the needed liberalization the State Bar Associations certainly should take action on their own, such as adopting the liberal education requirements of California.

Legal Truth, I agree that the ABA and state bars have a responsibility to review and reform a regulatory framework that has seen little change in decades. That said, I am not sure that deregulation will produce the required reforms. I would argue that the regulatory framework is overdue for a page 1 rewrite, and should not be scrapped until a sensible replacement has been drafted and adopted.

There should be a balancing that falls somewhere between the ABA and the AMA (a regulatory system that has curtailed the American educational opportunities to the point that we are unable to meet medical needs without importing foreign doctors). Likewise the state bars should revise their regulatory frameworks, and while I acknowledge that California stands as an outlier in its more flexible approach to educational requirements for bar admission, I am not sure that the resulting effect on legal education in the state is favorable.

To the question posed in the article, there are some schools that are taking steps to address the new market realities, and I would point to the University of Iowa as a school that has maintained its admissions standards, and decreased class size to do so. Its efforts to attract applicants have focused on cost and has announced its plan to reduce tuition. I have no idea whether it will work, but it signals an acknowledgement that the market for legal education has changed, and a willingness to act.

Finally, I would add that the decline of applicants/enrollees at law schools it not explained solely by the lack of legal employment opportunities. The lack of employment opportunities is compounded by the dramatic inflation of the cost of attending law school. Since 1975, the cost of tuition has increased at an alarming rate, and I would suggest that the cost now exceeds the anticipated return on investment for a huge number of potential applicants.

The points about

are all valuable contributions to my original article. Thanks.

All I would add re Iowa Law’s experiment is that while I have no idea whether it will work or not either, experimentation is exactly what we need a lot more of. As we know, the ideal solution is not always obvious and not always the first thing that comes to mind. How many years and generations of technology was it, after all, from the original (excoriated) Apple Newton to the Palm Pilot to the BlackBerry and finally to today’s smartphones and tablets?

Bruce, are you familiar with any historical examples of industries that faced a sea-change with similar features? I think that it could be illustrative to identify an example where:

a. Entry into the industry is controlled by a cartel;

b. Admission requires a significant initial investment of time and money;

c. there is no guarantee of admission or return on investment;

d. the public generally lacks accurate information or understanding about the industry and how it operates; and

e. technology and market forces are dramatically transforming the economic function of that industry.

The only thing that comes to mind immediately would be a guild or trade association that existed prior to the advent of organized labor. I was thinking about stone masons at the time when steel production transformed construction. I am not sure that any comparisons would withstand analysis, but perhaps there are lessons for the legal industry that can be gleaned by analyzing historical examples. If you had the time or energy to look into this, I would read it with enthusiasm.

Hayden:

A possible example would be diamond mining (and its downstream activities) prior to the entry of BHP and Rio Tinto into the Canadian deposits. It seems to me to match all five of your points. The vertically integrated cartel never saw it coming until it was too late: they didn’t believe the resource could be there; they did not imagine that anyone with the resources to invest would take them on; they did not imagine that their consumers (e.g., Harry Winston) would partner with their new competitors.

The analogy is not to law schools, so much as to alternative competitors that one simply assumed could never function successfully for the clients who were not nearly so captive as they appeared only a few years before.

Mark

The ABA’s representative blames law schools for not recognizing that the number of law students entering school in recent years was not sustainable, but the ABA seems unwilling to acknowledge its own role in the problem. A primary root of the supply problem is noted in the article. In the last 38 years, the ABA has approved almost 40 additional law schools. Apparently, the ABA never considered the effect of increasing the number of schools by almost a quarter in a relatively short period. The ABA had to have expected the number of law students (and, hence, graduates) to increase unless it believed that existing schools would shrink their enrollments, which was unlikely. The ABA needs to recognize its role in inflating the bubble, and allow the market to work. That means taking a serious look at the viability of all existing approved law schools and allowing some to fail. That may also include forcing the closure of some schools by revoking approval because sometimes the invisible hand needs guidance.

I don’t think the ABA can refuse to accredit a law school on the ground that the nation has an adequate supply of law schools already — that way lie the Scylla of the Sherman Act and the Charybdis of the Clayton Act. The ABA could, however, implement performance-based standards and reasonably say that a school that has (say) a 50% bar failure rate for two years running should lose its accreditation on the ground that it’s a failure itself.

Excellent Article.

“The State Bar associations and other Bar Associations seem remarkably quiet on this issue. They have a much greater incentive to turn around this decline than the ABA does yet we here very little, if any, response from them. They will pay the price in years to come as declines in bar fees and other fundraiser initiatives come as a result of a decline in lawyers. If the ABA does not deliver on the needed liberalization the State Bar Associations certainly should take action on their own, such as adopting the liberal education requirements of California.”

No, because the ABA doesn’t lose money if grads can’t get jobs, and they don’t even lose money if lawyers leave the profession, so long as there are replacements.