Last week I wrote about innovation and how the early adopters can gain sustainable competitive advantage.

This week is something of a follow-on, albeit one motivated more by recent personal events than frankly by brilliant editorial planning in advance.

The variation on innovation I want to discuss today has to to do specifically with innovations where your very decision to try it out can make success of the innovation more likely.

Lest this seem mysterious, I have two words for you: Network Effects.

In the wake of the (original) dot-com boom, we all learned a lot about network effects as every entrepreneur dreamed of launching a business blessed with their salubrious characteristics. Of course, claims often outran reality.

Before going further, I commend to you with the highest possible praise Bill Gurley‘s recent piece on his site, abovethecrowd.com, “All Revenue is Not Created Equal: The Keys to the 10X Revenue Club.” The title of the piece is actually quite humble: It’s simply one of the all-around best analyses of what goes into making strong business models that I’ve read in awhile.

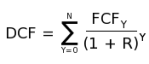

As a VC and a finance guru, one of the things Bill does all day is try to value companies. In doing so, it’s hard conceptually to beat our old friend, discounted cash flow:

The problem of course is that projecting cash flows for any company–much less a startup–can quickly become an exercise in imaginary numbers. Or, as Bill puts it,

[F]rom a purely practical view, the DCF is an unruly valuation tool for young companies. This is not because it is a bad theoretical framework; it is because we don’t have accurate inputs. Garbage in, garbage out.

Instead, Bill turns to indicia of “revenue quality,” which is shorthand for those characteristics which are all but certain to have a positive impact on DCF. He proceeds to discuss 10, and I’ll give the table of contents before taking this where I want to go:

- Sustainable competitive advantage (Warren Buffet’s Moat)

- The Presence of Network Effects

- Visibility/Predictability (of revenue)

- Customer Lock-in/High Switching Costs

- Gross Margin Level

- Marginal Profitability Calculation (this is basically a measure of whether there are economies of scale)

- Customer Concentration (a lack thereof, that is)

- Major Partner Dependencies (same)

- Organic Demand vs. Heavy Marketing Spend

- Growth

Since we’re talking about network effects, here’s Bill’s key observation:

In a system where the value to the incremental customer is a direct function of the customers already in the system, you have a powerful dynamic [generating the result that] the market leader has an unfair advantage that is reinforced by network effects. [Citation omitted.]

There are a few important things to remember about network effects. Some network effect systems are stronger than others. […] Second, networks effects are discussed way more than they exist. Many things people identify as network effects are merely economies of scale, which are not nearly as powerful.

I think for this audience most of the other tick boxes on Bill’s list are fairly self-evident, but perhaps “organic demand vs heavy marketing” deserves a word. Simply put, the more costly it is to gain a new customer, the less valuable your business, and the cheaper the new customer, the better. Nirvana is businesses that customers flock to voluntarily. To illustrate, Bill dusts off a slide from a Skype presentation a few years ago showing their cost of acquiring a new customer is $0.001, while for Vonage the cost was $400. Point taken.

And a word on Growth: Do not make the mistake of thinking it’s a per se good. There is such an (evil) thing as “profitless prosperity,” and during the original dot-com boom many entrepreneurs (according to Bill) figured out that if Wall Street was paying for growth, growth is what they’d deliver, goshdarn it. “What if I had a business where I sold dollars for $0.85?” That’s preposterous, of course, stated so baldly, but rampant as kudzu were startups offering customers “below market” deals. And yes, they were indeed too good to last.

The reason I spend a moment on growth is because of our obsession with it in Law Land ca. 1980–September 15, 2008. Query whether it even is a strategy, but we certainly acted as thought it were.

But this started off being about innovations, and innovations, yes, in Law Land.

It has often been remarked how we are a profession premised on precedent, and that’s utterly understandable and probably fine as a default assumption.

But I specified “profession,” not business, premised on precedent. Confusing the two, and applying the (il)logic of “because that’s the way we’ve always done it around here” to business decisions is a categorical error of the first order.

The always valuable Alex Novarese (editor in chief of LegalWeek) wrote recently about the UK firm Irwin Mitchell, which is planning to take substantial advantage of the Legal Services Act when it takes effect later this year (still scheduled for October). What are they doing? Alex wrote (emphasis mine):

The firm has obviously put years of thought into how it can utilise the volume side of its business while seizing on outside investment to achieve a major expansion in its high-end commercial practice, and so does look one of the best-placed firms to make this work In [their] case, you have to give the firm credit for genuinely embracing change and being ready to take a calculated risk. That’s what business – as opposed to a profession – is all about.

Now, to innovations with network effects: The very essence of there being network effects means that any potential participant who likes the idea but decides to “wait and see” is actually undermining the idea’s chances of success–or certainly the speed with which it succeeds, which can easily become the same thing.

We often assume, probably without articulating it consciously at all, that “wait and see” is the ultimate noncommittal approach: One where we might be said to first, do no harm.

This situation is the radical opposite. “Wait and see” inflicts harm not only on the courageous innovators who have decided to give the new idea a spin, it is one of the strongest steps a firm can take towards thwarting the future state they claim to desire.

Unhappy with the status quo? Presented with a possible alternative future vision, but one which requires buy-in by a significant proportion of the marketplace to be durable and of powerful value?

Then sitting on your hands is the most destructive action you can take. “Wait and never see,” indeed.

©2011 The New Yorker