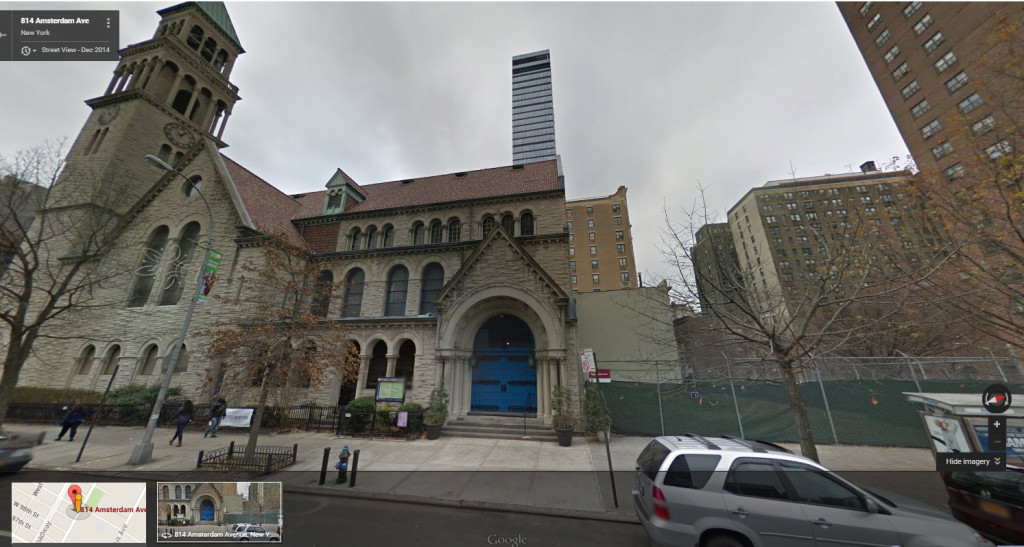

The doughty team from St. Michael’s Episcopal is now roughly two months into our engagement of an AmLaw 100 firm to help assess the zoning, land use, “open space,” and other issues surrounding our vacant corner lot and opportunities for development. (Earlier installments in this series are first here and second here.) Attentive readers may recall that we asked for an opinion from our firm within six weeks. Hence this update.

(1) So far we have received nothing whatsoever in writing from the firm. They’ve given us no reason to expect that will change, soon or perhaps ever.

(2) Without descending into irrelevant detail, a prior putative developer for the site had obtained building permits years ago which, mirabile dictu, are still in effect. While they’re in the name of that erstwhile developer and not St. Michael’s, and while they date to a prior zoning/land use regulatory regime, they conceivably have some value today, as bargaining chips if nothing else.

The associate assigned to the matter, who used to work for the City of New York in buildings, claimed she couldn’t locate them and essentially gave up on that bit of research.

As you might expect in 2015, such building permits are not only a matter of public record but are available online at nyc.gov; the ones I’m referring to are here. (I have never in my life visited the City’s Department of Buildings site and it took me less than a minute to find them.)

(3) We recently had a meeting scheduled with the partner on the matter at the firm’s offices in midtown. (I was not present.) Our representative—one of the two wardens of St. Michael’s—arrived about five minutes early and ran into the partner in the firm’s reception area; he was heading for the elevator to go out to get coffee.

He kept going.

My colleague sat in the conference room for 15-20 minutes awaiting his return. When he did appear, the plan was to conference in the other St. Michael’s warden on the speakerphone. He didn’t know how to do that.

Sometimes I fantasize that it would be liberating if Adam Smith, Esq. could delve into the genre of fiction, but such is not the path we’ve chosen.

I hereby honor my promise to keep this short.

You’d written that the church interviewed three firms, and that Firms A and B did remarkably similar presentations about their qualifications and expertise, without any specifics. Firm C sent a 6-page engagement letter.

Which approach won your hearts? Did the church hire Firm A, Firm B, or Firm C? Or did you find a Firm D?

I had the same questions. Bruce, I respect your writing and thought leadership on law firm management, but these anecdotes do not support your key theories. The church here was nonplussed with the candidate law firms, but appears to have hired one of those candidates anyway. Now, the church (through Bruce) complains about the service and lack of expertise provided by the winning law firm, but continues to retain the law firm. What incentive is there for law firms to improve? The church’s (like many clients!) revealed preference is that it will hire a firm merely because it is an am law 100 firm that purports to advertise a practice area matching the church’s needs.

Firm C.

Do these guys not know that you have a blog?

The strictly correct answer is “I don’t know if they know” but it would seem fairly plain that if they do know they haven’t visited recently. (And I have met with several senior partners in this firm in the past.)

At this point I don’t think the existence of Adam Smith, Esq. is exactly a closely-held secret. I’ve been publishing it for 13 years and the aggregate archival content (all on the server for the searching–storage space is cheap) amounts to the equivalent of four or five books.

To “Anonymous #1:” (about revealed preferences, a stalwart analytic tool)

Fair points. A few observations in mitigation, at least, if not exculpation:

As I say, not an excuse but perhaps “guilty with an explanation” is more like it.

Bruce, this is clearly going to be a large project, but if this is the only real estate that the church owns, the Big Firm may view the church as a one-off client, and thus as not being important enough to service properly. The lowest of the AmLaw 100 grossed about $320 million in 2014, so even if the church’s project will generate $500,000 in legal fees over three years, the church is no more than a 0.05% client to the firm, without the prospect of being a long-term client. Maybe a smaller shop would pay more attention?

Re: revealed preferences

Yes, well, one might also infer some preferences of the law firm from the available information:

“If you want to achieve excellence, you can get there today. As of this second, quite doing less-than-excellent work.” Thomas Watson

This is the communication you got from Firm C:

•fees and costs are not predictable and accordingly the Firm has made no commitment to Client concerning the maximum amount of fees and costs necessary;

•staffing of the matter may change at any time within the Firm’s sole discretion;

•one-tenth (0.1) of an hour is the minimum time recordable for any activity; and so on.

Is it time to counter (or too late to address this):

– Not paying for the time when a lawyer disappears for coffee.

– Not paying for time wasted figuring out how to use the firm’s own speakerphone for a scheduled meeting.

– Not paying for work that an inspired high school senior could do in a minute without any training. (See you example involving permits. I mean no offense, Bruce. I think you know what I mean.)

– Not paying for time for work that the client could do on their own – like conversations amongst themselves. (See speakerphone example, above.)

– Any commitment that you can withhold payment for contested charges? (The pubilicity for the firm to sue a chuch would be…undesirable, especially given your current narrative.)

Not sure the church is a big enough client to change the firm’s behavior.

Without meaning to pile on, this is just another example of how clients say they’re concerned about fees, but they really aren’t. This isn’t just the church, but it’s all those General Counsel who complain but also continue to hire the same old brand names. The market has not shown that firms are punished for failing to work efficiently (or, conversely, rewarded for working efficiently). Why should that partner not continue to walk out for coffee if he feels like it? He won’t even get fired from this job for being rude and unable to work a phone, much less that affecting any future engagements. If an entity with your direct advice won’t do it, why should we ever expect any different, anywhere else?

Bob Jessup