“Never before has our future seemed so shrouded in fog and noise,” I’ve written, and discussed its paralytic effects on our decision-making. Comes now academic vindication of just how strong the effect is.

But I’ve also dug up, from the same academic source (the Wharton School), a potential antidote. If we have the courage to embrace it.

The disabling power of having no forward visibility is recapped in “‘Uncertainty Traps:’ Why a Lack of Information Can Paralyze an Economy,” published last month in “Knowledge@Wharton.”

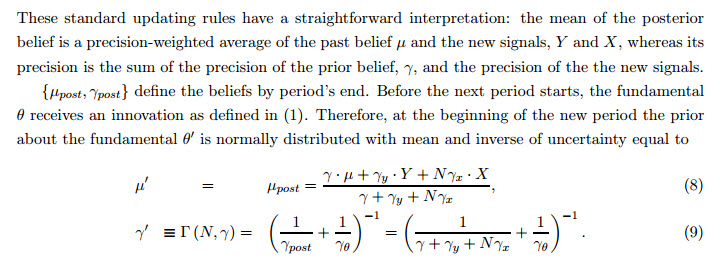

We know that no one is fond of uncertainty, but in relatively mild recessions it takes only a few augurs of good news to begin to revive the economy’s natural “animal spirits.” Deep recessions—that would be this one—create a self-reinforcing information vacuum where no one seems to be generating signals indicating a turnaround in the works. The academics (one each from Wharton, NYU, and UCLA) give their theory the full-dress graduate-level economics mathematical treatment in a paper, explaining for example, that “Standard [Bayesian] updating rules have a straightforward interpretation: the mean of the posterior belief is a precision-weighted average of the past belief û and the new signals Y and X,…”

(Toldja.) We’ll stick with the English language version.

But by way of digression, here we have an example of much of what I fear ails modern economic theory, at least as practiced in graduate programs at leading universities. The French economist Thomas Piketty, now on something of a victory lap up the East Coast in connection with his recently published book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a formidable, rigorous, 700-page history of wealth, and which improbably just made The New York Times best-seller list, acerbically critiqued his own profession:

“For far too long,” [he wrote,] “economists have sought to define themselves in terms of their supposedly scientific methods. In fact, those methods rely on an immoderate use of mathematical models, which are frequently no more than an excuse for occupying the terrain and masking the vacuity of the content.”

Back to the Uncertainty Trap: The heart of the theory is that at least as important to economic decision-makers in evaluating the state of the markets going forward is not just the goods and services being churned out, but the information that’s generated as a byproduct of economic activity. Not just macroeconomic variables like new claims for unemployment or housing starts, which are doubtless of great moment to the Fed Board of Governors, but less so to the managing partner of an AmLaw 200. The information that’s pertinent includes, “Is your competitor hiring? Opening in new markets? Investing in practice management or technology?”

“The production process itself generates information, and this information, at least some of it, is available to everyone in the economy,” [co-author] Taschereau-Dumouchel says. “When there is a lot of information, it reduces firms’ uncertainty about the economy, which makes more firms invest…. We are basically trapped in that bad state where uncertainty is high and the economy is not producing very much. Everyone is waiting for others to invest, which leads to no one investing.”

Commonsensically, much of the truly useful information flows through social channels, not BLS statistics. While more (positive) information is generally better, it turns out that less information is not worse simply in a linear way, but that below a certain threshold of a minimal amount of information, everything comes to a halt.

Fewer signals lead to greater uncertainty and less investment, and vice versa. But this ebb and flow is not steady. Below a certain threshold, information is so skimpy that investment virtually ceases. That stops the flow of social-learning information, creating a vicious cycle that becomes hard to break.

The authors note that “the long-run response to a temporary negative shock becomes considerably more protracted when the magnitude is above some threshold. The economy quickly recovers after a small temporary shock, but it may permanently shift to a low activity regime after a large shock of the same duration. In turn, a positive temporary shock of sufficient magnitude can put the economy back on track.”

So what, pray tell, is to be done?

The use of the mathematical symbols in the example or concerns that you don’t know what the R programing language is or why anyone would care should not deflect people from thinking and making decisions in a “Bayesian” manner.

Your firm has an “opportunity” to hire two new lateral partners, call them X and Y. You have a body of information about each of them through your due diligence. What should be your hiring position? The Bayesian analysis is to take advantage of what your firm’s prior history is with lateral transfers whose credentials are similar to those of X and y. On a frequentist basis let’s suppose that 3 of your last 6 lateral transfers have met their criteria for success at the time of hiring within a period of A years. Whatever you thought when you hired them, the posterior probability of success for lateral transfers is 0.5. That now is your best guess (the new prior probability) for success at your next hiring opportunity. So if you want to do better than toss darts, you need to mine the information on X and Y to see whether their cases looks more like the successful transfers (within the context of the next A years) or more like the unsuccessful ones. If X looks more like the successful pool and Y looks more like the unsuccessful, then your probability for success with X is > 0.5 (and maybe you can infer how much better at least semi-quantitatively), but the probability for success with Y is < 0.5.

If one has the (successful) experience needed to be making important decisions, my experience is that it should always be possible to make and defend an initial estimate of probability of success – even if that estimate is 0.5. This is not guessing or intuition, it is empirical analysis. Then in almost all cases is possible to adduce some relevant, additional information, and to use the “Bayesian” process for updating your estimates. As I am sure ASE will agree, this is exactly what is done with decision-making in other businesses – everybody makes decisions under uncertainty. Thinking as logically and quantitatively as possible not only clarifies and strengthens your risk (or opportunity) management, but it also allows the development of databases that can be used again for future decision-making. And so builds for the future and establishes a useful legacy.

Mark L.

Mark (and all):

As always, a cogent and thought-provoking comment which greatly extends and enriches the original subject I broached on ASE.

By displaying an excerpt of the actual published paper of our good Wharton friends – as opposed to merely excerpting the narrative executive summary published on “Knowledge@Wharton” – my intent was to vividly emphasize the hard theoretical constructs underlying their assertions which are deceptively commonsensical; casting doubt or ridiculing their rigorous approach could not have been further from my mind.

Truth be told, Thomas Bayes, father of Bayesian analysis (London/1702 – Tunbridge Wells, Kent/1761), and a Presbyterian minister to boot, has long been a hero here at ASE, if for no other reason than the enduring power of his insights.

In the famous Thinking Fast and Slow, Nobel economist Daniel Kahneman summarized Bayesian theory as helping define “the logic of how people should change their mind in the light of evidence.” Bayes’s rule specifies how prior beliefs or “base rates” (Mark’s 50% success here, for lateral partners) should be combined with new evidence (traits of X and of Y) to determine whether to favor the hypothesis over the alternative.

And indeed, every business makes decisions under uncertainty. That it makes lawyers squirm is all the more reason to employ every tool in the book to help optimize your outcomes.

Supporting those with ideas is the very least that should be done.

To do more would be to recognise the merit of the third of Professor Sargent’s lessons: “Other people have more information about their abilities, their efforts, and their preferences than you do.”

That demands of law firm (and other) leaders that they should actively seek out what is known beyond the C-suite and use that information to make better sense of what might work for the future.