If you think your firm faces new strategic challenges in the wake of the Great Reset, imagine if you had been running a global bank in 2009, where the entire regulatory, interest rate, competitive, and customer environments had shifted abruptly and substantially beneath your feet.

Thankfully we don’t have to imagine that: McKinsey has written the story of one such (unidentified) bank’s experience, and it holds lessons for us all.

Begin with the premise that suddenly pervasive and continuing uncertainty suggests that hands-on senior management involvement is more critical than ever. What exactly does that mean? What should senior management be doing, and when and how should they be doing it?

Lest you think we’re about to sink into an academic exercise, consider two simple facts:

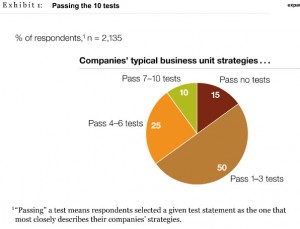

- Judging by their own characterization of their strategic planning process, barely one-third of firms surveyed (with a sample of 2,000+ executives) reported that their own strategies passed more than 3 of 10 critical tests designed to shed light on whether a particular strategy is actually likely to beat the competition. And

- Only one in three reported that strategy was revisited based on “issues as they arise;” the rest said it hewed to a pre-determined cycle or “has no single trigger” (a virtual confession that it doesn’t happen or happens randomly—good luck with that).

Here’s the dismal report card on the 10 key tests (the graphic doesn’t even display those reporting they pass 9 or 10 of the tests since at < 2% it’s too small to see):

Why is strategy planning so poor?

Almost the entire explanation can be laid at the feet of one simple phenomenon: Senior management doesn’t spend nearly enough time focusing on it.

McKinsey takes a hard-core approach to the time commitment:

Our experience suggests this probably means meeting two to four hours, weekly or every two weeks, throughout the year. Devoting regular attention to strategy in this way makes it possible to:

- Involve the top team, and the board, in periodically revisiting corporate aspirations and making any big, directional changes in strategy required by changes in the global forces at work on a company.

- Create a rigorous, ongoing management process for formulating the specific strategic initiatives needed to close gaps between the current trajectory of the company and its aspirations.

- Convert these initiatives into an operating reality by formally integrating the strategic-management process with your financial-planning processes (a change that usually requires also moving to more continuous, rolling forecasting and budgeting approaches).

You may think that level of commitment is exorbitant, but consider what this global bank—and yes, your law firm—are up against in terms of actually making directional changes: “The momentum of the institution is so strong that the ability to change direction quickly is limited. After all, the focus of the senior and top-management teams of most firms, most of the time, is on near-term operating decisions—particularly on delivering earnings [billable hours] in accordance with the financial plan [compensation system].”

What did our friends at the bank decide to do?

Not surprisingly for a global bank in the 2008—2010 time frame, their #1 priority was to focus on optimizing the balance sheet and improving its risk-adjusted return on equity. Your initial answer might be different—say, optimizing your talent pool and focusing on your best clients—but the follow-on decisions are where you have to figure out what that really means. Which clients, exactly, will become priorities? What happens to “deprioritized” clients? How exactly do we evaluate marginal talent?

I promise you the temptation will be to try to solve too many different things all at once, losing focus and dissipating (quite possibly) the entire investment of time, energy, and management focus up until then. So try a few simple techniques to restore focus:

- Place tight and realistic limits on how many issues senior management can pursue in parallel. 5? 10? 15? You’ll know when your team bumps up against its attention ceiling.

- Get very practical about prioritizing issues; a powerful technique is to allocate to each member on the task force X slots per meeting agenda, forcing them to focus on issues they think are truly critical. (Just make sure X is a small number, as in less than fingers of one hand.)

- Favor quality over quantity. If a core issue—whether to close an office or de-emphasize a practice area, for instance—deserves consideration, make sure the background analyses and reports people have in front of them in making that decision are of the highest possible degree of thoroughness and nuance.

Since the overwhelming likelihood is that few if any members of your top leadership team have a great deal of experience in strategy planning, it also helps to have a roadmap (lawyers love roadmaps anyway) to provide guidance on what to do. While there are any number of permutations on this, here’s a basic take on the steps involved:

- Frame the questions; what are the firm’s objectives and constraints? What possible “solutions” are off the table?

- Benchmark where you are; understand the true reality of the firm’s performance, its capabilities, and its sources of past performance.

- Look ahead; identify emerging trends and what they imply. Identify what remains uncertain.

- Posit options; what are your alternative paths to creating enhanced value? How might competitors be expected to respond?

- Choose. Create an integrated plan enumerating what you will do and what you will not do going forward.

- Commit to it. Develop an action plan, with individuals responsible for specific components, each with deadlines and milestones. Create and execute a communications plan.

- Refine and evolve. Track progress, determine midcourse corrections, and review.

Repeat.

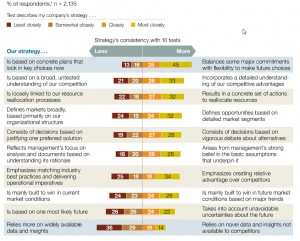

As you’re looking at the strength and precision of your strategic plan, it wouldn’t hurt to run it through the 10-factor checklist I referenced above.

Here they are:

Finally, know that this is serious business. Our friends at the global bank recognized shortly after they convened the strategy summit in 2009 with three individuals (the CEO, the head of the Global Investment Bank, and the head of the Domestic Bank) that the head of the Domestic Bank had to go. He did. And the story ends as the bank enters 2012 with the reality of its performance still falling short of its aspirations in the strategic plan. Realizing this, they asked the Global Investment Bank and the Domestic Retail Bank to identify new initiatives they could undertake to close the gap, or…revise their aspirations downward.

Turbulent times.

But the mature response is not to retreat into fear and paralysis-by-uncertainty, but to forge ahead when competitors are stuck.