Irish BIshop George Berkeley (1685–1753) famously asked, “if a tree falls in the forest and no one is present to hear it, would there be a sound?” His notion is neither as cutesy nor as vexed as it might strike you, but a snappy and memorable encapsulation in English of his belief that “esse est percipi”–to be is to be believed. HIs notion, so posterity teaches, is since humanity is limited in our perception to ideas and not matter itself, the supposition that our ideas reflect actual reality cannot be proven.

To this, shall we say, rather counterintuitive and attenuated invocation of scholasticism in the extreme, Dr. Johnson produced a devastating riposte:

One of the most ardent of the many critics of Berkeley’s philosophy was Dr. Samuel Johnson who is said to have famously refuted the eminent bishop’s theory of immaterialism by kicking a stone in the churchyard after one of Berkeley’s sermons exclaiming ‘I refute it thus!’

(From “Ask a Philosopher,” June 2012)

Be that as it may…..

If a law firm fails, or merges under conditions bordering on in extremis, do we “hear a sound” any more? (I am expressly not talking about the likes of Dewey, or other self-inflicted collapses brought about by extreme descents into philistinism.)

Comes news that Stroock & Stroock & Lavan is closing its doors, “with immediate effect,” after nearly 140 years. From the perspective of lateish 2023, not many can be surprised, but a few thoughts on context are in order to show decent respect, and are otherwise called for. Did or did not the failure of Stroock “make a sound?”

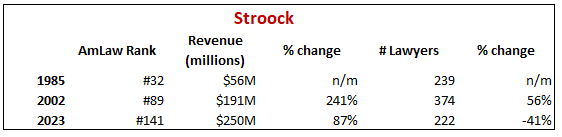

Since you’re reading Adam Smith, Esq., a few numeric datapoints are called for: This table shows the key AmLaw statistics for Stroock from 1985, the year the AmLaw was introduced, through 2002 (height of the following boom) through 2023, the last available data:

The arc tells a familiar story:

- From major league “player” in 1985 (especially considering it was essentially a single-city firm, even if that city was New York);

- Into a slow relative (but not absolute) decline at the height of the subsequent boom for the legal industry in 2002;

- followed by a quite material shrinkage on all key indicators to today, as we write.

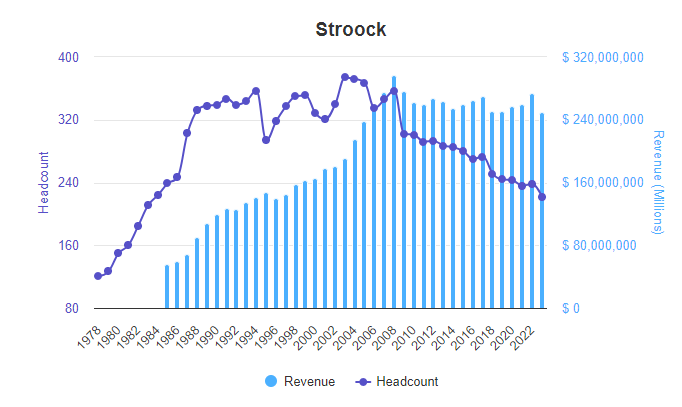

Here’s the past 45 years on two of our favorite metrics, gross revenue (duh) and lawyer headcount–also a “core” stat and virtually ungame-able unlike, say, some other headline numbers people like to trumpet (thank you, American Lawyer Media):

The story these numbers tell is straightforward and as it turns out definitive.

Now let’s shift gears to look at another high-profile firm that disappeared–in the form we all knew it for decades–in the last few weeks.

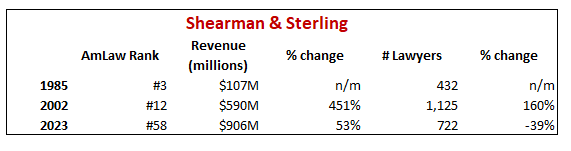

Comparisons can be invidious glib but we also see strong growth in lawyer headcount and revenue from Year 1 of the AmLaw stats (1985) to a decade ago, and then a shrinkage in headcount and drastic slowing of revenue growth from 2002 until the most recently released data.

But, you protest, Shearman did not fail as did Stroock. Strictly speaking, correct, but I would ask you to expand your imaginative filter and relax your literal/factual one when looking at this second table. I think you might describe Shearman’s trajectory as, “Not exactly outright failure, but….”

It’s imprudent to cook up dramatic generalizations from limited data, but what if these two outcomes are a distant train whistle coming from the horizon: Without resorting to invoking the Rorschach Test of generative AI and its potential implications for labor-intensive, bill-by-the-hour human intellectual labor (of which we will have more, much more, to say), a simpler and more straightforward thought might present itself to you:

In the era of NewLaw, supercharged performance by some elite law firms, and relentless client pressure on legal spend, maybe the “Hollow Middle” is no longer a realm to be occupied indefinitely and comfortably as long as it lasts, but a shrinking and unforgiving island?