With vaccines no longer a distant deus ex machina but here today in the cargo holds of aircraft at 35,000 feet, on FedEx and UPS trucks nationwide, and soon at a friendly neighborhood pharmacy near you, it’s time to refocus on what the contours of Law Land’s post-Covid world might look like. The only answer that I can guarantee will be dead wrong is, “Same as before.”

“Resilience” seems to have become the touchstone by which the difference between post-Covid acceleration and stasis will be determined. I have a different view, and I think it’s more than semantic.

Resilience is, we can stipulate, the capacity to bounce back and recover from adversity, but I think its conventional understanding stops there. We took the blows, we got back on our feet, and we’re standing right where we were flattened moments ago. The fire in the engine room has been extinguished, the damage repaired, and the ship is seaworthy again.

But “resilience” alone does not make it a better, faster, larger, more modern, commodious, or capable ship; it restores your losses and puts you back at Go.

The missing ingredients that post-Covid outperformers will add to mere resilience are learning and adapting. Learning plus changing based on what you’ve learned puts the “better” in Build Back Better. Let’s elaborate for a moment. Resilience entails:

- Containing the damage ASAP;

- Being decisive about cutting losses;

- And recovering more or less to the status quo ante.

Adaptability adds to that:

- A thirst for learning: Being non-judgmental about weaknesses potentially revealed and candid and forthcoming about the need to fit to the new world;

- Taking, intentionally, a longer view—beyond damage control in the immediate crisis;

- And creating options for your future.

Before imagining in a free-form and relatively undisciplined way what our post-Covid world might look like, can we draw any lessons from history? Anything to learn here from the past? (And no, I’m not talking about the 1918 Spanish flu.)

This being a publication centered around economic perspectives on things, our minds might revert to the 2008 GFC, the last big bad and still memorable Western World recession. What happened to Law Land emerging from that economically traumatic period?

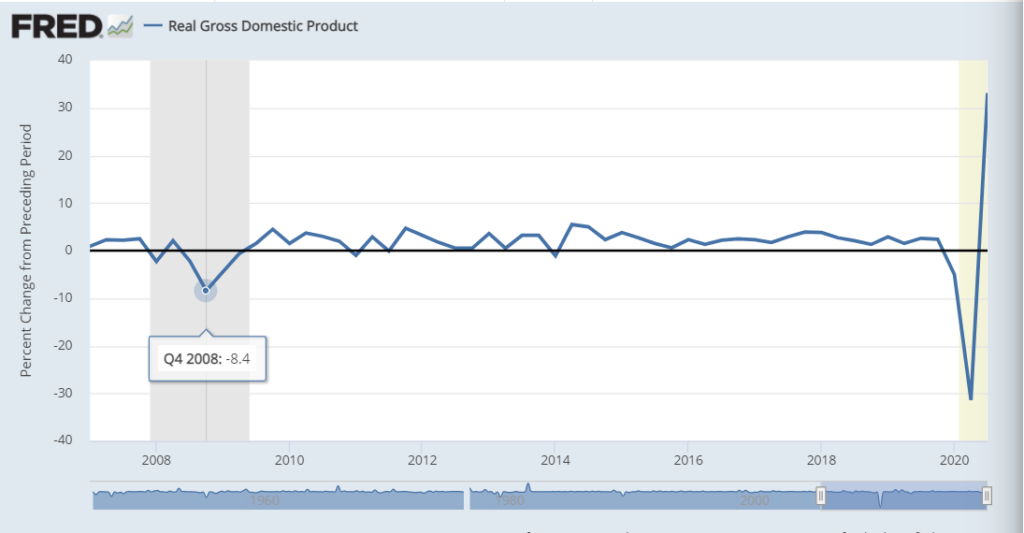

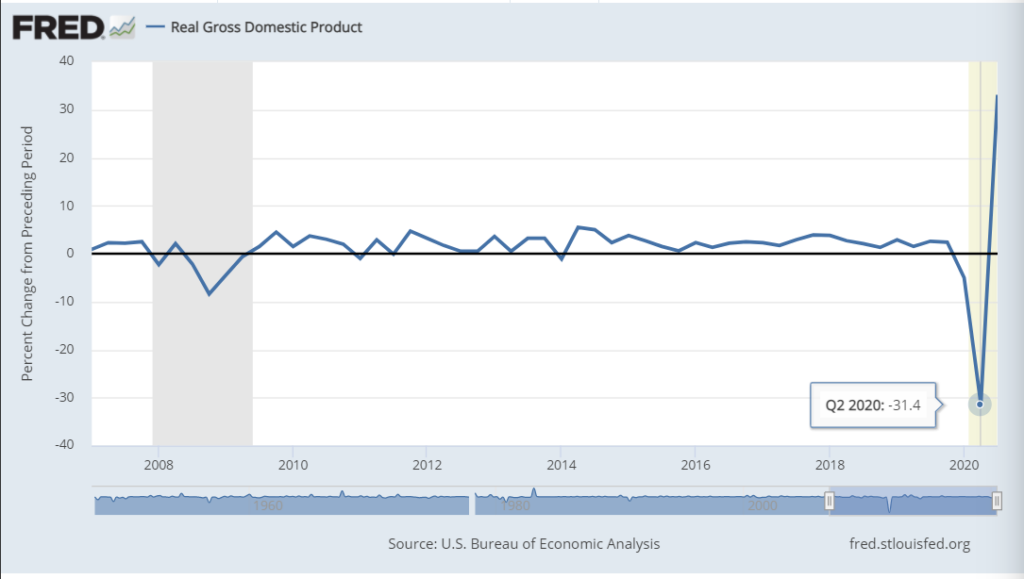

First, some data:

You can see that the 2008 GFC, severe as it was, was far less violent than the Covid-19 meltdown. A long list of differences between then and now explain this, but some of the headline reasons have to include, at least:

- The 2008 GFC was induced by a freeze-up of the financial sector. With everyone running towards safe, liquid, assets, lending and capital flows essentially stopped and save for the heroic efforts of the Fed, the TARP program, and shotgun mergers in the financial services sector, our recovery would have been far more prolonged and painful.

- The impetus for the Covid meltdown was of course not comparable in the least. Western World governments ordered large sectors of their economies to stop in their tracks.

And just as the precipitating events were quite unlike each other, the aftermath of these two recessions, it’s safe to predict, will be quite different as well.

Historically—as definitively outlined in Ken Rogoff’s and Carmen Reinhart’s 2011 This Time is Different: Eight centuries of financial folly—recessions caused by financial crises (government defaults, banking panics, currency debasements, large-scale asset bubbles, and more) are particularly long-lasting in effect. As we’ve written, a financial crisis is analogous to draining all the oil out of a car engine; everything is going to freeze up and some damage will be long-lasting. So unemployment remains high longer, GDP suppressed longer, consumer confidence shaken longer.

The global Covid-19 pandemic and its worldwide economic consequences—primarily in the form of shutdowns of selected markets—by contrast, suggests no reason to believe that the hangover will endure.

It’s worth a note that these “shutdowns” have had a myriad of causes, from outright government bans and prohibitions on certain classes of establishments like bars, restaurants, and “nonessential” shops, to far more widespread public anxiety at engaging in even permitted activity like flying, staying at hotels, or taking public transport, to what is effectively the total evaporation of demand for engaging in activities like attending live theater, opera, and other performing arts, or sporting events.

Why is this germane?