We have written before about the profession’s seeming disconnect between how people perceive the typical law firm, in terms of lawyer career-level distribution, and reality. The perception, from history, is that of a relatively small number of partners on top of a largeish associate base: The totemic pyramid. The present-day reality is a relatively smaller cohort of associates, a vastly expanded intermediate tranche of non-equity partners, and a top tier of equity partners shrinking in proportion over the past two decades: Our “diamond.”

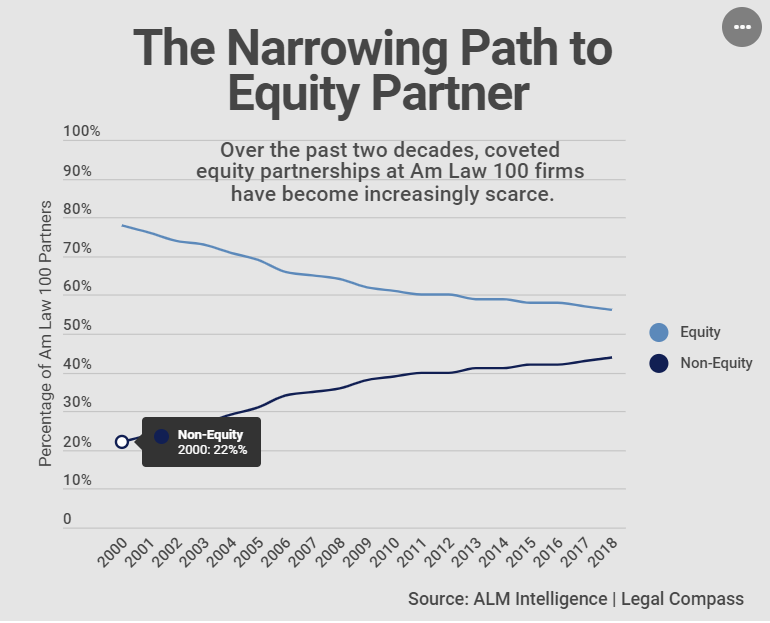

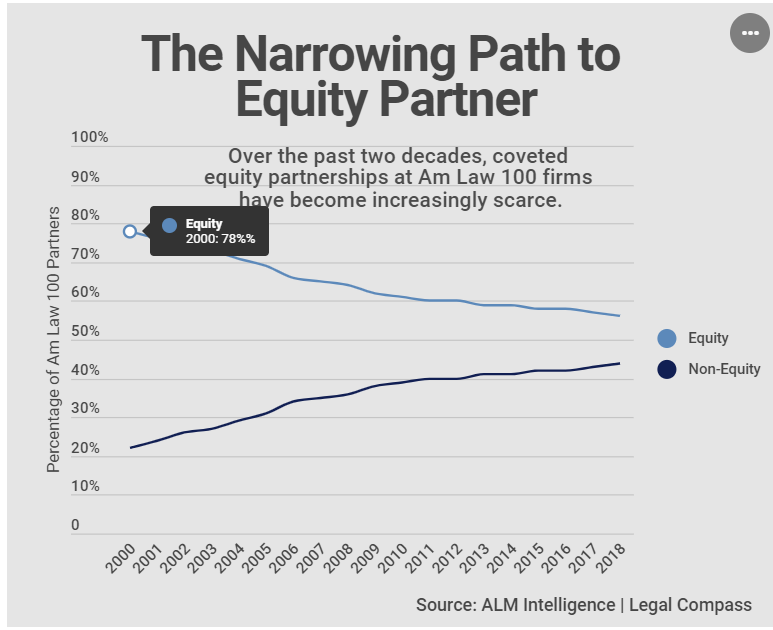

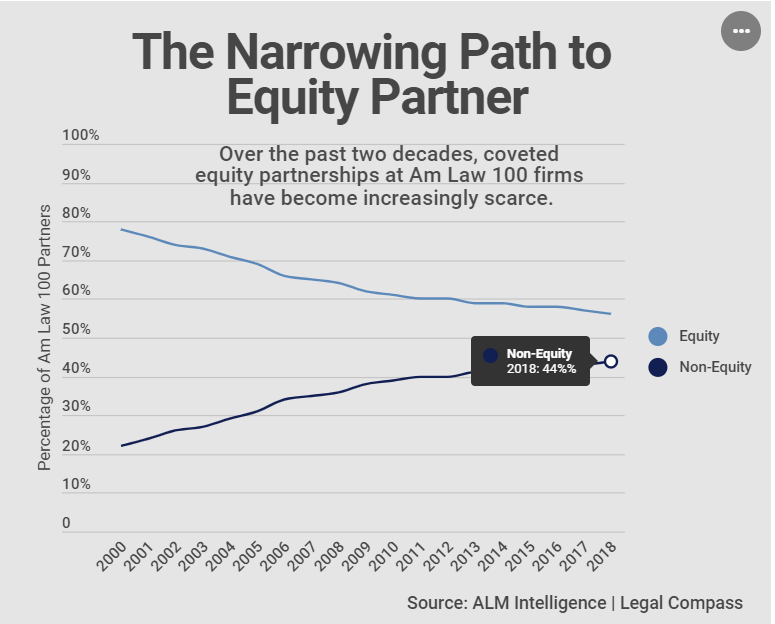

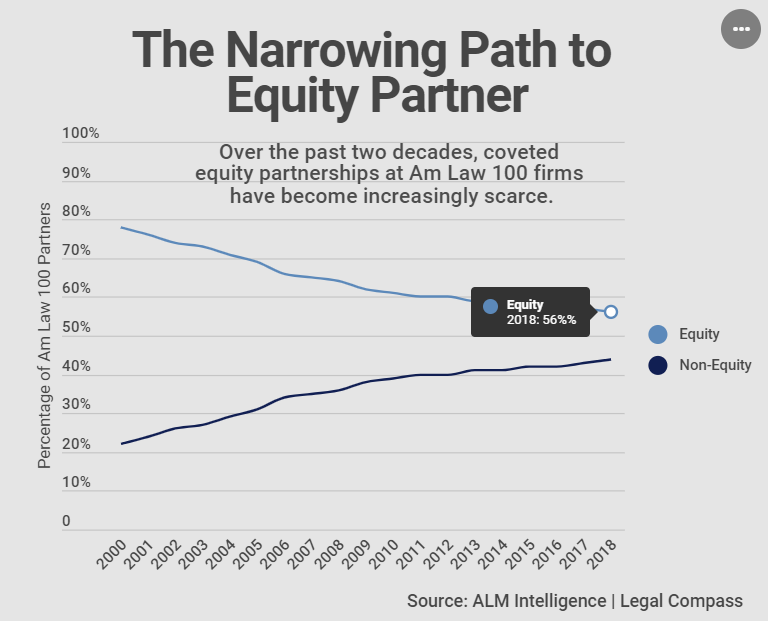

We’ve often noted that we feel competent at economic analysis but not at psychological insight, so I leave it to you to spin a theory or two about why we seem so enamored of the pyramidal paradigm, but new data just released by ALM Intelligence show just how radically this distribution has changed over the past two decades. Their sample set of firms is the AmLaw 100, but if anything had they included the second 100 the transformation would have been even more striking, and we have every reason to believe data would show the same migration were it expanded to the Adam Smith, Esq. equivalent of the “Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index” of law firms.

Some visuals make the point:

Shall we review?

- Equity partners as a share of all partners from 78% to 56% (call it three out of four to one in two), or down 40%;

- Non-equities as a share of all partners from 22% to 44%, or up 100%.

Not shown in this particular article but readily available from other sources is that non-equities are now approaching parity, in headcount, with associates.

Is this a good thing, a bad thing, or just, as they say, a “thing thing?”

Whatever we say next is guaranteed to provoke letters to the editor, so let’s just offer a few observations about pro’s and con’s.

The primary question is, “Why does your firm have non-equities [assuming, strongly odds-on, that it does]?”

Good answers:

- We instituted the non-equity tier as a “second gate” from associate to equity.

- Promising associates who’ve demonstrated they’re skilled practitioners and actually enjoy practicing law (read: they work hard) are promoted to non-equity rather than shown the door;

- Where, with “partner” on their business card and the full marketing resources of the firm behind them, have [3-7 years] to demonstrate whether they can actually develop substantial business of their own, in which case

- They are promoted to full equity

- Or else they don’t go up, they go out.

- We have a small handful of non-equities who are deeply adept at niche, but required, specialties which will never, by their nature, generate business but which provide essential support to our strategic core practices (tax is the classic example).

- It’s a temporary way-station for incoming laterals we need to prove out or for others entering or re-entering the firm after a career hiatus; and after that it’s again up or out.

- They are “service partners” in the truest and finest sense: They serve clients well, are experienced and thoroughly up the learning curve, their rates are relatively sane, and everyone needs a strong bench of solid players. We don’t expect them to be rainmakers.

- And we are superb at resource allocation so they don’t bottleneck associates’ getting the experience they need.

Bad answers:

- It’s a parking lot for B-/C+ players.

- They have high realization and decent rates so they make money for us,

- all the while creating a stout roadblock to senior associates getting exposure to the kind of work they need to advance professionally

- (that is to say, we do resource allocation in a haphazard, improvisational, and thoroughly unprofessional manner)

- “We have that many non-equities?! How did that happen?”

- Management can’t stand having awkward conversations.

Wherever your firm comes out on these questions, ask yourself whether the compelling data on the growth of non-equities, at the relative expense of associates and equities, means leverage is dead. Because if leverage is receding like the tide, you may have to re-examine the model of how you translate revenue into profit. Now that is an interesting business challenge.

Bruce, is is possible that the shifting of employed lawyers in large firms from associates to non-equity partners is a rational business response to two trends in litigation, which is more highly leveraged than most transactional work? I have in mind (1) outsourced legal services are handling work that firms had given to associates, and (2) sophisticated clients don’t want to pay for inexperienced lawyers working on their cases. The first factor means that a top-end litigation partner who brings in and supervises four big cases a year and who used to generate (say) $5 million/year of work for junior lawyers in the firm now generates only $4 million/year of work for junior lawyers in the firm – the lost $1 million for the firm has been replaced by $600,000 of fees going to outside providers. The lost $1 million of work also eliminates work for 2 or 3 associates. The second factor means that clients are more willing to pay for senior associates and persons with the title of “partner” than for newbies. The firm might rationally (i) hire fewer new associates and keep its current associates longer, and (ii) inflate titles a bit to satisfy the demands of its clients. If both effects exist, and I think they do, then we would expect to see the leverage ratio decrease, the number of new hires decrease, and the average tenure of employed lawyers increase.

Per your data, NEPs have become a significant segment of leverage for many law firms. The challenge here is that they are a very expensive type of leverage. Unless a firm can contain and control the cost (comp) for this segment and keep their rates tracking up, they become a drag on profit. An additional challenge is that to keep them sufficiently busy to maintain margins, they inevitably take work away from associates and counsel, which is another drag on profit. Stated differently, “diamond” is a euphemism for fat in the middle. Thanks for sharing your insights as always.

Toby:

Thanks. I agree with you that NEP’s are the most expensive type of leverage, not just because they’re paid more than associates but because they work (industry wide average data) 100+ hours/year less than associates. So their cost/hour is higher still.

Your point (which I also make in the article) about their taking appropriate and necessary (for training and professional development) work away from associates can be easily solved by assiduous resource allocation, and we all know that’s a core competence of the vast majority of law firms. (Said no one, ever.)

Also: the fear if you don’t give someone the magical status of partner, another firm will.

Touche. “TItle inflation” has come to many industries!

I also believe e-billing technology has allowed for greater insight into corporate legal spend making it easier for a GC to justify expanding their internal staff, which we have seen over the past decade. In-house salaries have been increasing because of increased demand. More generalist/low-level work is being internalized, thus lesser demand for young associate headcount. I also don’t believe this is just a ‘law firm’ issue. It is a ‘firm’ issue you can see across a lot of industries.