Back in March we first wrote about the theretofore-inconceivable systematic attack on BigLaw by our current Administration in Washington, DC. The “program of revenge,” as we described it, calculatedly targeted law firms representing clients and interests that the White House viewed with disfavor.

Legalities and political stances aside (I’m not a practicing lawyer and Adam Smith, Esq. is resolutely not a political forum), this squarely poses the challenge to our industry of whether collective action in the face of a threat to the Rule of Law is something we can respond to with a united voice or whether we will instead dissipate our collective power as each firm pursues its own individual short-term self-interest. So far our leading firms are choosing to protect their individual profit by ducking their heads and muzzling their voices. Believe me, I understand the reasoning.

So, for that matter, did David Hume back in 1738 when he predicted the behavior of two neighbors wishing to drain a meadow [archaic punctuation retained]:

Two neighbours may agree to drain a meadow, which they possess in common; because it is easy for them to know each others mind; and each must perceive, that the immediate consequence of his failing in his part, is, the abandoning the whole project. But it is very difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons should agree in any such action; it being difficult for them to concert so complicated a design, and still more difficult for them to execute it; while each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expence, and would lay the whole burden on others. [His Treatise of Human Nature (1738-39.]

Since it’s now well settled that BigLaw has failed to answer the Administration’s bitter and lawless shakedowns of leading firms with anything approaching collective action, let’s delve a bit more deeply into the economic theories that might explain this perverse and self-defeating response. Perhaps the closest analogy to how we’re behaving is the well-studied thought experiment referred to as the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a game-theoretical concept developed in 1950 at the legendary RAND Corporation think tank. It goes as follows.

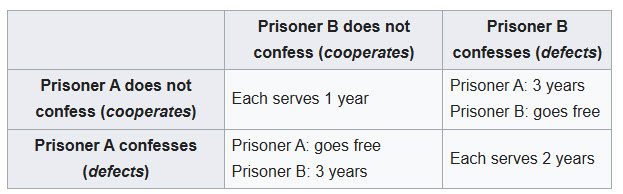

Imagine two presumed felons arrested for a single crime and incarcerated in separate cells with no means of communication. The police don’t have enough evidence to convict both on the most serious charge they could bring, so lacking that they ask both to confess. Here’s how this hypothetical plays out [courtesy Wikipedia.]

Obviously, both are better off if neither confesses, but equally obviously the rational choice for each–ignorant by force of what the other has chosen–is to confess.

This encapsulates for me the dilemma faced by each individual BigLaw firm in the face of the Administration’s extortionate demands. Self-interested rationality dictates “confess” (accept the Administration’s demands). And that is the behavior we have witnessed.

Could it have been otherwise? Certainly. But we’ve made our choices and it’s too late to revisit them. Blame lies not with the Administration–they were just opportunists seeing what they could get away with–but with us. If there’s a next time, let’s pray we may have learned something.