“Ripped from the headlines,” as the cliche-inclined might say, we have this from The American Lawyer in the past week or so: Elite Firms Revisit Comp Formulas as Star Talent Has ‘Extraordinary Leverage’ Some highlights:

- According to Kent Zimmerman over at Zeughauser Group, “firms are setting out strategic goals like increasing the ratio of highest to lowest paid equity partners.”

- Protecting a firm’s most lucrative practices from partner poaching by higher-paying firms is difficult without “decompression” of the pay scale, i.e. widening the pay gap between highest and lowest paid partner in order to reward the highest-producers.

- And lest there be any doubt what’s motivating this: “Some of the high-performing partners are the biggest drivers of change,” Zimmermann said. The invariably astute Brad Karp of Paul Weiss puts it more plainly: “Star talent has extraordinary leverage right now.”

This particular American Lawyer article is not a random data point, it’s part of a large and by now fairly coherent canvas depicting generational shifts in elite law firm partner compensation.

The industry veteran Hugh Simons fleshed out one dimension of this in his recent column on In-House Counsel: Big Law’s Clear and Present Danger:

The paradox with all of this is that, despite two decades of downward demand pressure, law firm profit-per-equity-partner (PEP) has never been stronger. The data provide the explanation: from 2000 to 2022, equity partners as a portion of all partners at the 25 most profitable firms have declined from 82 to 57 percent and leverage has grown from 3.0 to 5.1. The accompanying human dynamic is that what it takes to be an equity partner has changed from being a great lawyer, to being a great lawyer who brings in business, to now being a great lawyer who brings in business and pushes it down for others to do. Equity partnership at a modern elite law firm is not a tenured position; rather, akin to the partner-track associate ranks being up-or-out, equity partnership is now perform-or-out. This change is cascading through all of Big Law.

It’s hard for many partners to accept that this is happening. It’s a violation of the implicit social contract that attracted them to the profession. Alas, the economic forces driving the change are as inexorable as they are unjust (published 27 Sept 2023)

Or, as I might put it even more plainly: The rich are getting richer in Law Land.

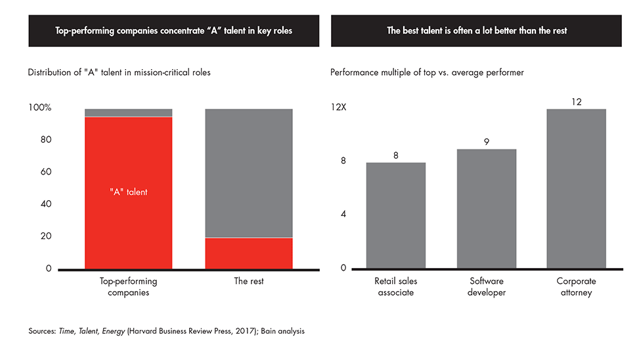

Bain published a book five years ago (Time, Talent, Energy [Harvard Business Review Press: 2017]) that contained this arresting graphic:

May I summarize what you’re seeing?

- First, “A” players occupy close to 100% of “mission critical roles” in top performing companies, but less than 20% of those roles in “the rest” of companies;

- And, specifically germane to “corporate attorney,” the performance multiple of “top” people vs average performers is twelve to one—the highest ratio displayed and higher even than standout software developers, which is famously a category that rewards superstars.

In my own book, Tomorrowland: Scenarios for law firms beyond the horizon (2017, available here), I devoted a chapter to “Talent and Free Agency Win.” In it, I laid out examples from industries including best-selling authors (using Amazon’s “Author Rank”), sports stars, rock bands, investment money and hedge fund managers, movie stars and so on–familiar examples all. But I also cited economic/labor market research showing the same pattern of growing income inequality within any given professional calling held true for “virtually every subgroup that’s been studied [including] dentists, real estate agents, authors, attorneys, newspaper columnists, musicians, and plastic surgeons. It holds true for electrical engineers and English majors.” [Robert Frank and Philip Cook, The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us (New York: Penguin: 1996), emphasis supplied]

Now, whether your reaction to this strengthening and accelerating trend is “Harrumph, back in the day I had to walk 10 miles to school” or “It’s about time,” a calmer and more helpful perspective might be simply to try to understand the economic forces driving these shifts. Is this phenomenon a revolving door—we can always go back out whence we came in—or is it a ratchet, once it’s clicked over there’s no return?

To shed light on this I will take you to an article published in The American Economic Review, by Prof. Sherwin Rosen of the University of Chicago, barely a dozen pages long: The Economics of Superstars (Rosen, Sherwin. “The Economics of Superstars.” The American Economic Review, vol. 71, no. 5, 1981, pp. 845–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1803469).

Its opening sentence:

The phenomenon of Superstars, wherein relatively small numbers of people earn enormous amounts of money and dominate the activities in which they engage, seems to be increasingly important in the modern world.

Might I stress that this was published over 40 years ago? We are not dealing here with a transitory, cyclical, or evanescent phenomenon. And “superstars” happens to be not just a catchy word to insert in the title, but profoundly descriptive. For starters, it connotes a market drastically unlike the standard Econ 101 model, where “products are assumed to be undifferentiated and one seller’s products are assumed to be as good as those of any other” (Rosen at 845).

Without wasting much time, Rosen addresses how the “talent differentiation” model applies to Law Land:

Lesser talent often is a poor substitute for greater talent. The worse it is the larger the sustainable rent accruing to higher quality sellers because demand for the better sellers increases more than proportionately: hearing a succession of mediocre singers does not add up to a single outstanding performance. If a surgeon is 10 percent more successful in saving lives than his fellows, most people would be willing to pay more than a 10 percent premium for his services. A company involved in a $30 million law suit is rash to scrimp on the legal talent it engages. (Id. at 846. $30-million in 1981 is the equivalent of nearly $120-million today–Bruce)

But why limit ourselves to the late 20th Century? I claimed that this phenomenon is “not transitory,” and indeed Rosen cites the great economist Alfred Marshall writing at the close of the 19th Century in his Principles of Economics (Macmillan and Co., London, 1895, at 775), who nailed this dynamic in the context of lawyers

The relative fall in the incomes to be earned by moderate ability is accentuated by the rise in those that are obtained by many men of extraordinary ability. There never was a time at which moderately good oil paintings sold more cheaply than now, and at which first-rate paintings sold so dearly. A business man of average ability and average good fortune gets now a lower rate of profits than at any previous time, while the operations, in which a man exceptionally favoured by genius and good luck can take part, are so extensive as to enable him to amass a large fortune with a rapidity hitherto unknown.

The causes of this change are two; firstly, the general growth of wealth, and secondly, the development of new facilities for communication by which those, who have once attained a commanding position, are enabled to apply their constructive or speculative genius to undertakings vaster, and extending over a wider area, than ever before.

It is the first cause that enables some barristers to command very high fees, for a rich client whose reputation, or fortune, or both, are at stake will scarcely count any price too high to secure the services of the best man he can get (emphasis supplied, archaicism’s retained).

You are at liberty to celebrate or to denounce the arrival of this economic phenomenon at the house of Big Law. You are not at liberty to ignore it or wish the world were otherwise.

Bruce – very astute, as always! I enjoyed this very much. I’m curious about the Bain book you cited above; did the author go into definitions of “mission-critical” roles and what those look like across various industries (but especially within law)? And, when looking a “superstars” – what qualities do these individuals possess?

Dear Lynne: First off, thank you most sincerely for your very kind remarks. I put a lot into what I do and that at least a few smart people seem to appreciate it means the world to me.

Now, as to your question: I must confess I did not read the entire Bain book, but now I am motivated to go back and do just that. The book–Time, Talent, Energy-– is here: https://www.bain.com/insights/books/time-talent-energy/

As you know, at Adam Smith, Esq., we make it a habit to draw learning from non-Big Law contexts, and this struck me as answering to that call superbly. If you do happen to read the Bain book, I’d be most interested in your thoughts!

Surely, avoiding risk is a huge influence on price for value. Given the persistence if the Power Law, it makes a lot of sense the test what if anything would change pricing if perceived risks are changed.