Something that feels structurally different seems to have developed in the lateral market.

The ambition of this essay is to describe what we think it is, why it has developed, and what it portends for the future of BigLaw. Plus, with any luck, some ideas or at least clues as to how you might deal with it.

What’s happening? Our great and long-time friend, Jim Jones, senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Legal Profession at the Georgetown University Law Center, recently called it “the era of the storm.” Now, Jim (and we love this) has never shied from the well-turned phrase, but we might amend his statement into the form of a question: “Is it the era of a storm?”

Those arguing this is nothing new and we’ve seen it all before have ammunition to support their view.

- It has been true for 20 years, +/-, that partners have enjoyed lateral mobility across firms, even at the higher-end and more prestigious heights of the profession.

- Similarly, market transparency has been increasing lo these many years: Initially mostly in terms of who was moving where, but for some time now including chapter and verse on compensation anticipated and/or guaranteed, roster of clients coming along for the move, and so forth.

- And the lift-out of entire groups (40 lawyers from Stroock to Paul Hastings!) is news for half a cycle.

To condense this plus ca change attitude into a somewhat cynical formulation, law firms are vulnerable to departures. News flash!

We disagree. Something is indeed different.

To reach back for a deeper understanding of the market dynamics of what’s going on, one can find no better starting place than Sherwin Rosen’s immortal (well, in certain circles!) The Economics of Superstars, Vol. 71, No. 5 (December 1981) of The American Economic Review, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1803469. Despite its dating back over 40 years, Its opening sentence announces everything you need to know and sounds shockingly contemporary:

The phenomenon of Superstars, wherein relatively small numbers of people earn enormous amounts of money and dominate the activities in which they engage, seems to be increasingly important in the modern world.

A little over a decade ago The New York Times summarized a then-new book (The Price of Everything, Eduardo Porter [Portfolio: New York, 2011]) with some examples from sports, pop music, and, yes, executive pay:

IN 1990, the Kansas City Royals had the heftiest payroll in Major League Baseball: almost $24 million. A typical player for the New York Yankees, which had some of the most expensive players in the game at the time, earned less than $450,000.

Last season, the Yankees spent $206 million on players, more than five times the payroll of the Royals 20 years ago, even after accounting for inflation. The Yankees’ median salary was $5.5 million, seven times the 1990 figure, inflation-adjusted.

What is most striking is how the Yankees have outstripped the rest of the league. Two decades ago. the Royals’ payroll was about three times as big as that of the Chicago White Sox, the cheapest major-league team at the time. Last season, the Yankees spent about six times as much as the Pittsburgh Pirates, who had the most inexpensive roster.

[…]But this is not specific to baseball, or even to sport. Consider the market for pop music. In 1982, the top 1 percent of pop stars, in terms of pay, raked in 26 percent of concert ticket revenue. In 2003, that top percentage of stars — names like Justin Timberlake, Christina Aguilera or 50 Cent — was taking 56 percent of the concert pie.

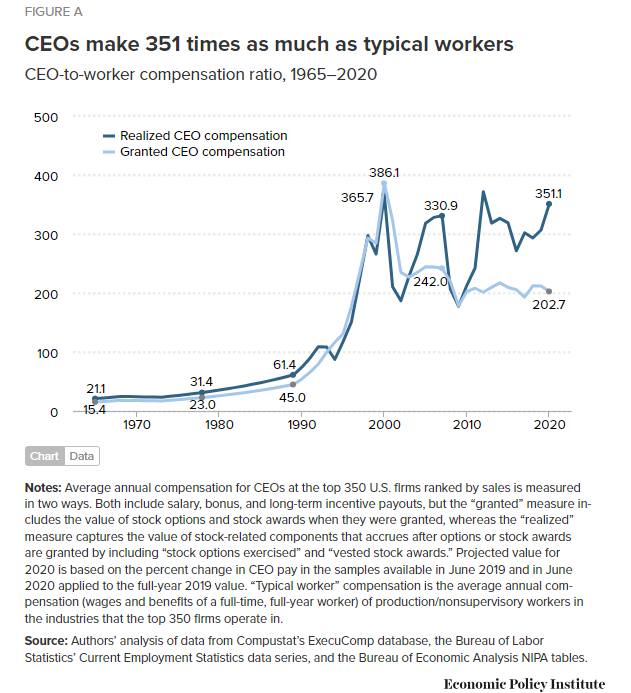

[…]. In 1977, an elite chief executive working at one of America’s top 100 companies earned about 50 times the wage of its average worker. Three decades later, the nation’s best-paid C.E.O.’s made about 1,100 times the pay of a worker on the production line.

Today of course we assume the new reality is here to stay. And you don’t have far to look to understand the economic dynamics driving this. All of these markets–sports, pop music, best-selling authors, CEO’s, and, yes, law firm partners, are labor markets where talent is the key differentiator. We can assume for simplicity, and for our sanity, that the distribution of talent in any of these fields of endeavor is “normally” distributed along the familiar bell curve. The critical distinction comes when it’s time to determine compensation, because the rewards accruing to people in these markets are distributed anything but “normally;” They are distributed along a power or exponential curve. It’s been said that the best software coders/developers are 10x or 100x as productive as run of the mill coders, and figures from Amazon will tell you up to the minute how much more popular Danielle Steel, Harold Robbins, or Barbara Cartland are than yours truly.

It’s a very short step indeed from that inescapable premise about talent markets to Law Land’s career structure of non-equity partners making very respectable, but not dynastic, annual incomes vs. superstars being paid $5-million/year, $8-million/year, and on up to the sky’s the limit. And here’s one more thing that has changed, at least from where we’re sitting: The reaction to these eye-popping figures used to be, “How can that possibly make economic sense?!?” News flash: Evidently they (mostly) have and mostly do. At least if you judge by the reality that such deals keep occurring, more frequently and at ever higher P/E multiples. The “not rational!” objection was rooted in a supposition about the way the world actually works, and that supposition has been disproven.

For comparison, the 351:1 ratio as of 2020 was 61:1 in 1989 and 21:1 in 1965.

But back to BigLaw.

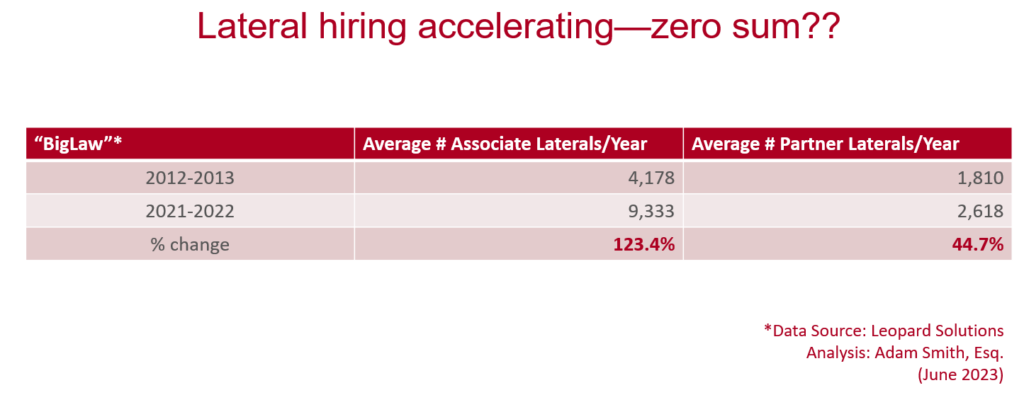

Without doubt, lateral movement is accelerating. Consider these statistics we just put together a couple of weeks ago for a presentation at a firm:

We headlined it “…zero sum??” to pose the obvious question: If it’s all musical chairs (ignoring the exorbitant cut for recruiters), who’s really winning here?

To be sure, some number of those 2,618 lateral partner moves last year were indeed to the proverbial “better platform.” But how many? 2,500? 2,000? 500?

Economic reality, and human nature, would argue that liquidity in and of itself can drive markets higher. That is to say, the more money is available to recruit talent, the more movement there will be, whether or not it all makes cold hard financial sense. “FOMO” is not exclusively the province of adolescent TikTok-addled victims or meme stock Reddit bandits.

Here’s what’s changed in a nutshell: No firm–no firm–is immune from being raided. Perhaps five years ago–certainly ten–Managing Partners of the super elite firms had better things to worry about than their crème de la crème being poached, but if it’s not near the top of their very short list of preoccupations today they are out of touch with reality. Love it or hate it, this is truly new.

Or, as one unidentified managing partner recently told Bloomberg’s Roy Strom:

“The market is out of control, and it feels like all firms, no matter how strong or profitable, are at risk of other elite firms willing to offer lavish, extravagant, irrational amounts of money to lift partners in strategic practice groups,” one managing partner at a Top 25 law firm told me this week. “No one is immune. The world has just become this lateral playpen.”

Is this good for the industry? For your firm? We have more than sufficient confidence in our readers to predict that you are answering, “No, couldn’t possibly be.”

But sadly (tragically?), it doesn’t even seem to be good for the laterals careening about:

“It’s all up for grabs,” another managing partner at a major firm told me last week. “Nobody wants their career careening from guardrail to guardrail. They don’t want huge peaks and valleys. They want stability.”

If this sounds hellacious to you, what’s to be done? I wish I had more solidly comforting counsel. But “failures of collective action”–as we arguably have here–are intransigent beyond all reason or common sense. The syndrome is that everyone finds it in their own self-interest to keep doing what makes the community as a whole miserable and worse off. This is a devilishly difficult cycle to break out of. In fact, absent some intervening exogenous factor, the only way to break the logjam is through the buildup and then release of an enormous reserve of pent-up potential energy–turning it into the kinetic force it takes to divert the course of the accelerating status quo.

Nice in theory, rarely spotted in the wild.

In the meantime, fortify your firm’s Czech hedgehogs and dragon’s teeth defenses–the economic and financial firepower it will require to fight back and hold your own or gain ground. Otherwise….. Well, “otherwise” we won’t go there.

Behold the Lateral.

Photo by Chris Chow on Unsplash

Here is a trend I am noticing in my little ecosystem with respect to “team” acquisitions, which most assuredly is NOT the NYC ecosystem you describe above. A true “#1 option” is worth the overpay, and probably more (maybe sometimes much more if you really hit a home run). You can tell almost right away if the diligence on the book was done correctly. But you frequently overpay for the #2 as well, if you are judging solely on their own numbers, and on down the line depending on the size of the team. And their contributions can be more hazy, especially when you are talking multiple years. Yeah, clearly the #1s leave money on the table to keep their troops happy, and that’s just normal compensation politics. But the real challenge is holding the comp numbers of those support players steady over multiple years (likely because of a guarantee structure, explicit or implied) when you have some incumbents who are clearly more productive but making less money. That is a HUGE source of discontent with team acquisitions, even though the overall deal may be making money (maybe). It really takes a few comp cycles to straighten all of it out on the back end.

Dear Skeptic: Fascinating contribution; thanks.

Taking your observations and remarks at face value, I am tempted to conclude that you have substantially raised the bar for what might be deemed a “successful” (financially accretive) lateral partner group acquisition. You are correct beyond doubt that team members down the pecking order from “#1” need to be factored into the calculus, and that they may on a strict cost accounting basis be deemed unprofitable–but that their being included is essential to the group moving over to begin with.

Tying that to your final, and too oft overlooked or underappreciated, observation about the sometimes powerfully felt resentment of the loyal good firm citizens who are feeling dissed by all the TLC being lavished on the new arrivals, says to me as a (hypothetical) MP of this firm that I better double over backwards, and then do it again, to communicate the all-in “package” value of the team coming on board to the entire partnership. In my experience MPs and their senior leadership colleagues cannot repeat this message too much.

Many thanks again,

Bruce