Remember these?

We made it customary here at Adam Smith, Esq. to publish a “Letter from….” after our return from any meaningful business trip to noteworthy cities. And, thankfully, here we are.

When you’ce been away from anything–a Great City, an old friend, a childhood neighborhood, a young man or woman–for over two years, one expects to see change. Did we ever!

The first compulsory observation is to note that the British economy has suffered more than its share of the normal global array of insults and obstacles to progress and growth. If not quite “Czech hedgehogs and dragon teeth,” then at least, shall we say, unforced errors.

Setting aside the recent spasm of gratuitous fireworks over Liz Truss, the “mini budget,” and the historic and shocking seizing up of the gilts market, the shadow that looms over all, scarcely mentioned any more, is of Brexit. How bad is it?

The sturdy and indefatigable FT recently inaugurated a new series, “Brexit: the next phase,” with some sobering statistics. Just for starters, in 2016 (the year the “leave” referendum was approved), the British economy was 90% the size of Germany; today it is 70%. And the average real disposable income per UK household is projected to drop 7% over the next two years. Need I add that this is the kind of loss people notice?

It’s the only one of the G7 nations with a smaller GDP than pre-pandemic:

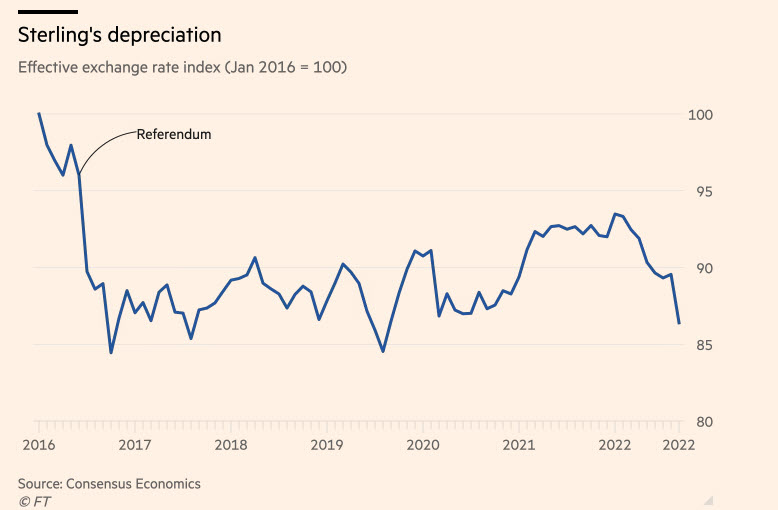

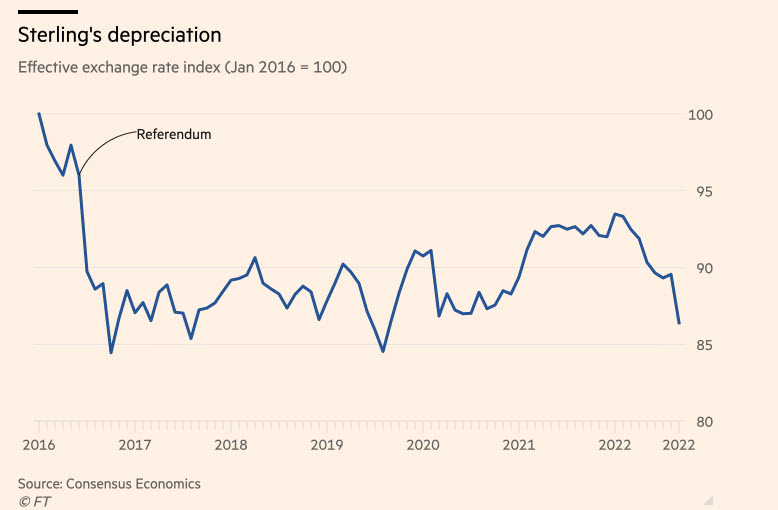

The pound immediately found a new stable trading range about 15% below its historic average:

Business investment seems locked at pre-2016 levels whereas it had been projected to be over 150% of that level before the “leave” vote.

All the while the loudest sound coming out of Westminster on these facts seems to be silence while resolutely looking the other way. Would it be salting the wound or “only fair” to immediately add that there is no going back, so perhaps resignation is prudence and wisdom incarnate.

Be that as it may, here we are.

I have written many times, as it bears repeating, that Law Land swims in the sea of Macroeconomic Performance. So what did we see last week in one of the world’s great city-states? Three strengthened or reinforced developments struck us, none altogether novel but today at a level of prominence and seeming inevitability that they did not rise to in the Pre-Pox Era.

One: Solidly established, large, middle market firms have found a viable niche indeed.

Not to tag any specific firms by name as stronger or weaker than their brethren, but for example it was ancient history when the Eversheds Sutherland transatlantic merger was novel and the transaction has long since been well and conclusively bedded down. Indeed, to speak to leaders there (we did), it’s unlikely even to come up unless you raise it. BCLP also seems to have found solid footing and is sailing forth with unitary Managing Partner leadership. Pinsent Masons was named Legal Business‘s 2021 “Law Firm of the Year” for its strong financial performance allied to client service and innovation, and they must be doing something right as the past eight years (the tenure of John Cleland as MP) saw their revenue grow 64% and the opening of ten new offices.

The list could go on, and we do not cite these firms, again, as especially virtuous or notorious, simply as representative of the breed. “Know Yourself” would not be the worst motto for them.

Two: Ought the Magic Circle to find some new identity?

Again, we know all four of these firms (yes, some better than others) but we are increasingly persuaded that the durable “Magic Circle” tag, these days, describes…..? Well, what does it describe? How much commonality remains–and truth be told, the moniker was always smarter as an ear-wig catchphrase than a description of reality on the ground and in the wild.

Each of the four has taken a quite distinct approach to international expansion, most pointedly when it comes to the US. Linklaters seems to have adopted, “Just say no,” Freshfields is investing at eye-watering scale in one and perhaps two US metros, CC has been quietly, relentlessly, and profitably growing Stateside for nearly a quarter of a century without causing any perceptible ripple among the commentariat. (Is it as simple as not raising your head above the Tall Grass? Is that the blunt instrument that attracts the media glare?) And A&O, of course, is on Plan C after the [non] O’Melveny merger.

But despite my writing this from our home base in the heart of one of the world’s other truly great city-states, it’s not all about the US all the time. The contrast in approach among the Four was meant to underscore their heterogeneity, not to put the US at the fore. (Need I mention these are UK law firms?)

Two other characteristics of the Magic Circle seem more prominent than perhaps they were perceived in the past. First is their extensive build-out of EU, EMEA, and Asia-Pac office networks. A&O has 41 offices worldwide, CC 34, Linklaters 31, and Freshfields 27.

Management strategists (Adam Smith, Esq., LLC, for one) might have questioned under truth serum before The Pandemic whether that didn’t seem like an awful lot of bricks and mortar, but we weren’t asked and weren’t about to volunteer.

But.

We–you, everyone–has heard and will hear it said that the pandemic “changed everything.” Of course it did nothing of the sort. But it did change how the world sees the role of The Office in virtually any company, but in talent-intensive professional services more than most. In a word, what offices are “for” has been transformed never to return to pre-lockdown days, for the simple reason that Work From Home works. If an office is no longer a pricey piece of commercial real estate in a Class AA building meant to house worker bees at their computers, what is its purpose? The smartest and most thoughtful firms are asking precisely that question as leases come up for renewal. And while this is not a column about the “WFH/RTW” debate–that is already getting old and tiresome to our ears–it is in passing a column about how much bricks and mortar is enough and how much is too much.

[If you insist on our thoughts about the brave new world of the office, they are straightforward: (a) people will not be in the office five days a week or zero days a week; (b) in particular, people will not go to the office to do desk/computer work; (c) the new highest and best (only?) purpose of the office will be for communal, collaborative, joint work–be it internally with colleagues, externally with clients, or a mix. So (d) any and all office designs from say, early 2020 and before need to be thrown out.]Which brings us back to the Magic Circle. Is the reality that “the sun never sets” on these firms an asset or a liability? We exaggerate; there’s no substitute for global reach. But at what scale? Four offices in Germany alone, for example? Management and operational overhead, infrastructure costs and travel logistics, profoundly rate-challenged local economies, volatile currency swings, abrupt and unwelcome political disruptions–all take their toll. Historically, empires expand their reach, achieve an apogee, and begin to retrench. It’s not retreat, not surrender, it’s prudence enlightened by new and irrefutable proof that white collar professionals can be every bit as effective remotely as on the ground.

Second is their bedrock assumption that they could rely on their all but impenetrable grip on the major UK banks as marquee clients as far as the eye could see. This assumption is anything but a dead letter, don’t get me wrong. But it’s not quite as ironclad as it forever seemed.

Finally, a dose of perspective: Each of these four firms is without doubt one of the world’s leading law firms, and it would take a lot more than a Global Pandemic or some bloody noses in the US market to shake that.

But if you want a suggestion for a quick thought experiment you can perform at home vis-a-vis the stature of the Magic Circle, ask yourself the last time you thought about, or read a breathless article about, the great inevitabilitiy of a transformative Magic Circle/Wall Street White Shoe Elite merger. I rest my case.

Third: US firms are anything but niche players in the London market these days; they have gone mainstream

In time immemorial, a handful of super-elite US law firms established tiny beachheads in London, primarily to serve their stalwart banking and investment banking clients who had gotten serious about the UK and the EU markets. (London was and, Brexit notwithstanding, still is, the gateway to the EU.) As the US financial behemoths grew and realized how much money was to be made across the pond, their law firms grew with them. The relatively short-lived, but powerful, Eurodollar market helped draw the spotlight to the UK and the Continent. (For background on this thread, see “Bretton Woods and the Eurodollar,” St. Louis Fed, 2022.)

Today Kirkland has over 300 lawyers in London, White & Case about 400, Latham nearly 500, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

What has changed is that US firms are no longer confined to their gilded cage of private-equity, hedge fund, non-bank bank sector clientele. Some time ago, US firms began to break these boundaries and expand their reach in financial services to the mainstream banking sector, allied industries, and of course the related but much broader practice areas of M&A, commercial real estate, project finance, intellectual property, taxation, and much more. Nor is their “industry” the tentpole of financial services alone: It’s infrastructure, high-tech and software, and nowadays essentially the entire for-profit commercial sector of any major industrial power.

But here’s what was new to us this trip: US firms are now making the “panels” of FTSE 100 corporations for their regular recurring, go-to, non-life-threatening work. In other words, US firms are going mainstream in corporate UK and corporate EU. Earlier we talked about a few things that would never go back to the way they were. Here’s a development profound enough to serve as the coda to today’s essay, “what did you see in London?”