Across my desk a couple of weeks ago came an advance copy of Glory Liu’s Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher Became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford: 2022).

The author, although a new name to me, is far more than amply qualified to produce such a volume. From her own website:

I am a lecturer in Social Studies at Harvard. Previously, I was a postdoctoral research associate at the Political Theory Project at Brown University from 2018-2020. My research interests are in the history of political thought, American politics, and political economy.

[…]

I received my PhD in Political Science in 2018 from Stanford University, where I was a Geballe Dissertation Prize Fellow at the Stanford Humanities Center, as well as a Gerald J. Lieberman Fellow, one of the University’s highest distinctions for doctoral students. I hold an MPhil in Political Thought and Intellectual History, a secondary MPhil in Classics from the University of Cambridge, and a B.A. in Political Economy and Classics from the University of California, Berkeley.

I do not need to tell you that Adam Smith is a subject of profound fascination to me, but this book promised to address his importance and place in the world from a perspective I had never spent much time thinking about.

Originally published in 1776, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations was lauded by America’s founders as a landmark work of Enlightenment thinking about national wealth, statecraft, and moral virtue. Today, Smith is one of the most influential icons of economic thought in America. Glory Liu traces how generations of Americans have read, reinterpreted, and weaponized Smith’s ideas, revealing how his popular image as a champion of American-style capitalism and free markets is a historical invention.

Drawing on a trove of illuminating archival materials, Liu tells the story of how an unassuming Scottish philosopher captured the American imagination and played a leading role in shaping American economic and political ideas. She shows how Smith became known as the father of political economy in the nineteenth century and was firmly associated with free trade, and how, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, the Chicago School of Economics transformed him into the preeminent theorist of self-interest and the miracle of free markets. Liu explores how a new generation of political theorists and public intellectuals has sought to recover Smith’s original intentions and restore his reputation as a moral philosopher.

Charting the enduring fascination that this humble philosopher from Scotland has held for American readers over more than two centuries, Adam Smith’s America shows how Smith continues to be a vehicle for articulating perennial moral and political anxieties about modern capitalism.

It delivers on that promise.

Based on the pre-publication commentary–the vast preponderance of which is from people I know and respect in the field–perhaps I should feel less abashed or inadequate at never having given real thought to Adam Smith’s place in contemporary American discourse. For example:

“Adam Smith was a moral philosopher well aware of the quirks of human psychology. So how is it that in America he wound up as the poster child for a free-market order that rests on false assumptions about human hyperrationality? This fascinating story is very important, very instructive, and has never been told. Glory Liu tells it with great verve and great charm.” J. Bradford DeLong, author of Slouching towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

“The import of Adam Smith in America is a hitherto neglected topic for understanding both Smith and the history of the nation. Glory Liu admirably fills this gap, reflecting a great wealth of learning and reaffirming the critical role of Adam Smith and his ideas for our world.” Tyler Cowen, bestselling author of The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream

“Adam Smith’s journey from Kirkcaldy to Chicago was a long, winding, and fascinating one, as Glory Liu brilliantly demonstrates. Adam Smith’s America draws on a vast array of source material to make that rarest of things, a genuinely new contribution to the field.” Dennis C. Rasmussen, author of Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders

“Glory Liu’s engaging and thorough study tells an important story that has largely gone untold. Her documentation of the complex and often surprising reception of Adam Smith in American politics and economics from his day to ours will be of interest both to students and to advanced scholars and indeed to anyone who may have wondered what all the fuss over Smith is all about!” Ryan Patrick Hanley, author of Our Great Purpose: Adam Smith on Living a Better Life

Many readers of these pages might be familiar with the famous “Adam Smith Problem”. The “problem” is that his 1776 Wealth of Nations is far more famous than his equally important and penetrating 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Wealth of Nations, of course, it is not an exaggeration to say, provides a blueprint for modern capitalism as we know it. Moral Sentiments, by contrast, was a far more passionate and compassionate book about why we care as a species so much for the lived experiences of our neighbors and fellow citizens. Or, as Smith expressed it with far greater eloquence and power (in perhaps the single most quoted extract from Moral Sentiments:

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

The so-called Problem boils down to the vastly oversimplified notion that capitalism is red in tooth and claw whereas “sentiments” for our fellow humanity are soft and impractical.

I have personally never seen, or experienced, the conflict, but barrels and barrels of ink, or pixels, have been spilled on it. I simply see Smith as a wide-ranging thinker in the area of socio-political economy and an astute and penetrating student of what motivates human beings, which indeed ranges from compassion to self-interest, all within the same body and brain each of us possesses.

“We contain multitudes,” as Walt Whitman instructed, and for anyone capable of serious and sober self-reflection, one has to recognize conflicting impulses within oneself. Compounding this is a simple fact of history. Smith has been dead for over 200 years (1790) and as a subject of more or less intense scrutiny for much of that span, pretty much any theory plausibly on the map, and some not, has been floated.

Rather than trying to pin Adam Smith down in some contemporary taxonomy of thinkers, or in the past or present under whatever ideological cause one is predisposed to advance, it might make more sense to try to take his thinking at face value and discern what its implications might be for today or the issue du jour.

This ultimately seems to me to be the value in Liu’s book. As I mentioned at the outset, it is not a perspective on Smith that I had ever given much thought to, but it may be the only intellectually, culturally, and emotionally honest way to grasp the commodious span of his thinking.

It’s only fitting to give the last word to Glory Liu (pp. 302-303 of her book):

This, then, might be the ultimate Adam Smith problem: Can the historical recovery of Adam Smith’s thought–’what he can legitimately be said to have intended, rather than what he might be said to have anticipated or foreshadowed’–ever be truly separated from recruiting him to serve our present political and intellectual needs.

The history I have documented here reveals that not only is the historical recovery of Smith compatible with his enduring political resonance, but also that belief in Smith’s enduring political resonance is perhaps the reason why so many people are seeking deeper inquiry into his works in the first place. We turn to Smith time and time again because we believe the history of political thought might help us tease apart the different sorts of political vision that are currently relevant to us or because ‘We need a new master narrative for our times,” yet as soon as we have created a new master narrative around Smith or identified a suitable political and moral vision from his Works, history renders Smith elusive again .

[…]

Perhaps we might be better off admitting that we are not immune to the missteps of the past, and that we cannot fully shed our prejudices, and that our political and intellectual expectations when reading (and re-reading) Adam Smith’s works will inevitably shape our view of him, despite our best attempts to do otherwise. If nothing else, we stand to gain a greater self-consciousness–not in the sense of whether we have the correct reading of Smith, or whether we are better or worse than those interpreters who came before us, but in the sense that we learn more about why we are reaching for Adam Smith’s ideas in the first place what are we asking Smith to do for our political, moral, and economic thinking in the 21st century?

If we can answer these questions and do our thinking for ourselves, perhaps we will be worthy of learning from Adam Smith after all.

I said the last word would be Liu’s, but I lied.

As your scribe and publisher, for my money the ultimate interpretation to be drawn from Adam Smith’s life, most definitely including Wealth of Nations and Theory of Moral Sentiments, is that he may have done more good for more people in the world than any other mortal.

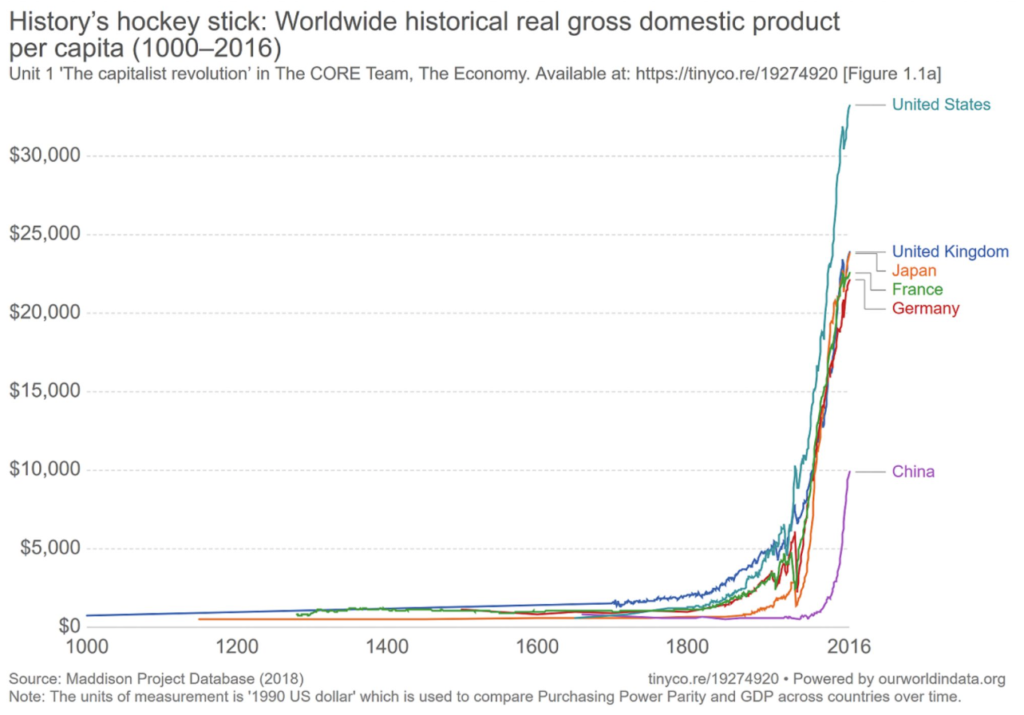

If you doubt me, just look at this.