Geography–a “sense of place”–is often taken for granted as the inevitable but fundamentally random by-product of historical happenstance, and almost never appreciated for the strategic dimension it provides–like it or not. Because it’s seen as foreordained, law firms leaders assume it’s a given in their strategic planning.

We count ourselves among the guilty. In our own Taxonomy: The seven law firm business models (2014), we in retrospect diminished it by limiting its import to only one of the seven archetypes: “Kings of Their Hill,” local hero law firms known as the go-to place in XYZ metropolitan area.

It’s time to revisit this assumption of assuming geography is in the spectator stands and not on the playing field.

Here’s our new working hypothesis in a nutshell:

- First, we stand by our “Kings of Their Hill” model as introduced in Taxonomy. Local hero go-to firms have and deserve to be on firm footing on the market landscape. They serve a purpose; clients understand the firm’s raison d’etre, its lawyers and business professionals can immediately recite unaided what it stands for, and they have built a moat around their market positioning–a barrier to entry. (If your firm doesn’t have one, you want one; if you do have one, safeguard it with your life.) The relevance of geography to Kings of Their Hill speaks for itself. If you are at one of these firms: Don’t muddy it up!

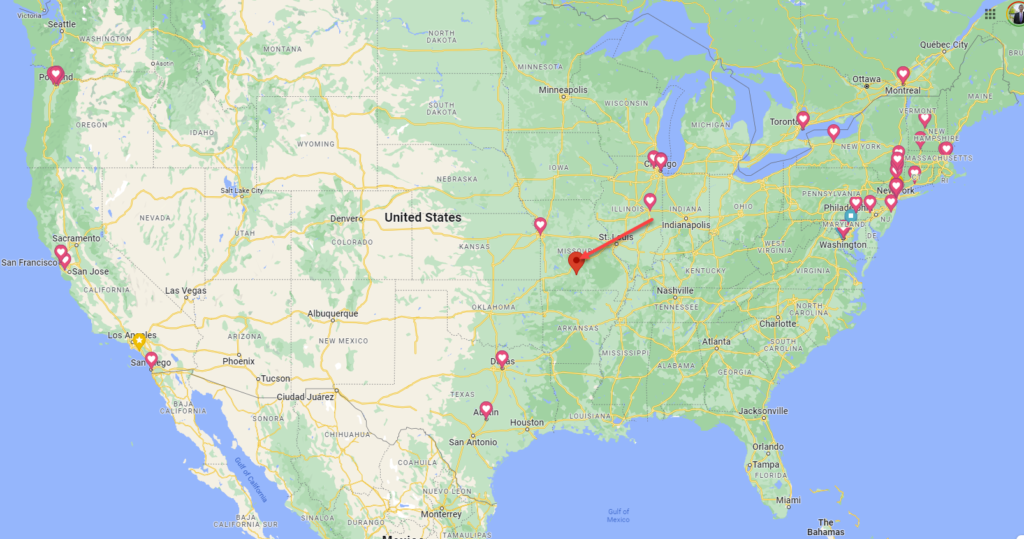

- Second, a number of firms over the years have completely jettisoned their original geographic roots. This is perhaps easier to exemplify than explain. The answer to all of the following questions is “No” and the reasons, although they differ by firm, are also, we submit, self-evident to anyone with the most modest exposure to the BigLaw landscape:

- Is Latham a California firm?

- Kirkland a Chicago firm?

- Goodwin “from Boston?”

- K&L Gates, or Reed Smith, identified with Pittsburgh?

- Cooley a creature of Silicon Valley?

- You get the idea. All these firms–all firms–began life as very much of a time and place. Some have decided, and it is a decision as well as a years-long plan of action, to shed that portion of their identity. By contrast, other firms which might superficially have sprung from similar beginnings remain quite identifiably a creature of their origins, and it redounds to their advantage in market perception.

- Wilson Sonsini and Silicon Valley

- Vinson & Elkins and Texas

- Williams & Connolly and DC

- Third, firms that remain closely identified with a City, count it as their headquarters, often basing the majority of their management and executive leadership there, retaining a mindset of hub and spokes or home office and satellites. But: These firms are not Kings of Their Hill at HQ. They are regional, national, or even international firms composed of an archipelago of territories or colonial holdings, principalities, if you will, gripped firmly in the orbit of the mother ship.

With that background, we can get to the good part.

Which of these geographic caricatures models provides a strong strategic grounding and which confuses the market and distracts from crisp and objective internal decision-making?

We’ve already turned our cards face up (eight years ago, already!) for Kings of Their Hill. We like this model a lot, because only one firm per Metro area can own it and the one who can claim it has something no one else does. Given what the world learned during the interminable Covid lockdown about “WFH” (it works!), that may be officially deemed a wasting asset, but in the meantime only the firm’s own ineptitude or inattentiveness can take away from them.

The second model also makes sense to us.

Note that there are two variations on this branch of the taxonomical tree: Firms who have credibly, legitimately, and once and for all left behind all but the most residual and latent fingerprints of their place-specific origin story. These firms are truly international (if they choose to be) or just plain national. Melting pots, if you will, agnostic as to where clients and lawyers originally came from. This locale-dispassionate calling card makes sense to many clients and prospects.

Second are firms who proudly maintain a sense of “home” and translate that into reinforcing and strengthening their marketplace identity and imparting an inchoate but palpable sense of identity into their offering typically through association with the marquee industry dominating their home base–High Tech for Wilson Sonsini, energy for V&E, governmental investigations and prosecutions for Williams & Connolly.

But alas, this brings us to the third model:

FIrms with a legacy HQ and dominant home office that may have and often has in fact long outlived its usefulness or relevance. But its dominion remains because whenever a major decision is to be taken internally at the firm, people reflexively ask, “What would [Boston/Chicago/Dallas/Seattle] do?” Because that’s where the firmly established center of gravity of leadership and tradition lies. The strategically smart question should never be (the implicit but unacknowledged) “What are the powers that be in [Boston] thinking?” but “What’s best for the firm?” We all know this, and I apologize to your intellect, Dear Reader, for stating it so baldly, but we all know this happens all the time.

I did a search of the management literature for insights into the strategic dimensions of geographic choice, and while there’s not much there’s at least a bit of support for our thesis here today from Harvard Business School’s “Working Knowledge,” in an article titled Location, location, location. Ignoring considerations inapplicable to Law Land (“resource availability,” anyone?), the bottom line in making the go/no-go call on planting a new flag should be the cuttingly simple, “What can we do there better than our competitors?”

This takes us right back to the strategic and conceptual flaw in fixating on a legacy Home Office-centric solar system for the firm when it has long since ceased to be relevant to the market. Why does that have any relevance to the market? (It doesn’t.) If the acid test is (and it is), “What can we do there better than our competitors?”. that hurdle has to apply equally across the board to all of the firm’s offices, regardless of age, pedigree, or (historic and happenstance) primacy.

One of the all-time great management books on strategy is A.G. Lafley and Roger Martin’s Playing to Win. (Disclaimer #1: There are damned few. Disclaimer #2: We happen to swear by it.) Its core message in essentially captured by the title. Winning firms play to win, everyone else plays not to lose. Which, again, brings us straight back to the error of the ways of legacy-centric firms:

- This orientation begins and ends with the firm, and its internal political dynamics: With the firm’s largely unexamined preferences, the comfort level of its lawyers and staff and leadership, and the fact that it’s familiar.

- It turns its back on a client-centric or market orientation.

- It is designed not to lose.

If this is your firm, need I specify, chapter and verse, what to do?

Things change. So must you

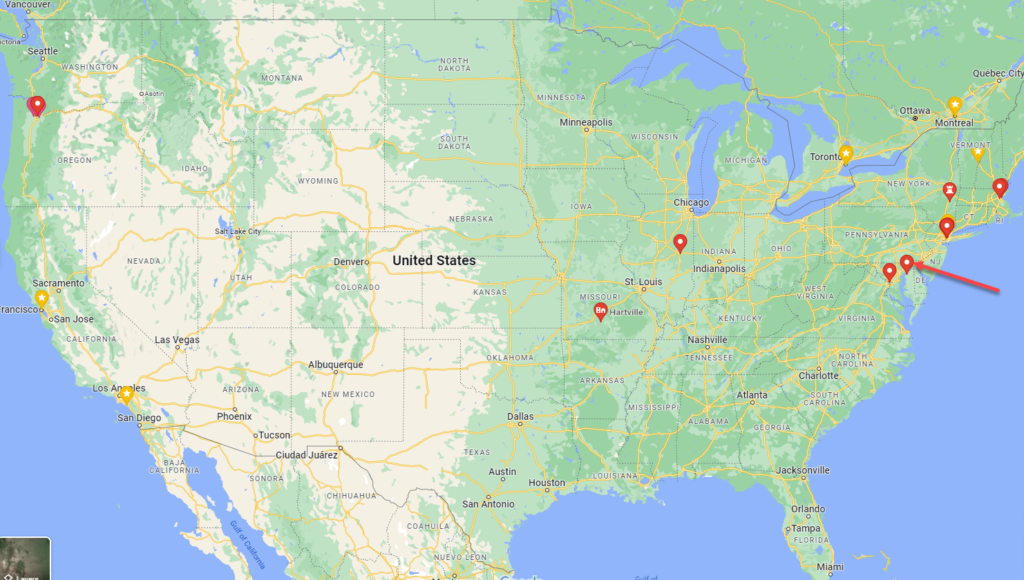

If only one firm in a market can be King of the Hill, the local market may nevertheless harbor two or three princelings. My west coast city (large but not among the largest) had for decades two large local banks, each with its own law firm. One had the King of the Hill; the other had the most significant princeling (call it “Prince Hal”). A third bank grew from small to middling and its firm became the second princeling (call it “Prince John”). Prince Hal’s bank got bought out and was eventually merged into a bank from Somewhere Else. Prince Hal still got bank work, and was its local counsel, but it became less significant.

Then one fine day Prince Hal lured the King’s bank to switch firms. The King picked up Prince Hal’s now-less-significant-locally bank even as Prince John’s bank and the firm itself continued to grow.

But then the banks of Prince Hal and Prince John were bought out and merged into banks from Somewhere Else. The King, who had been looking around the west coast, absorbed a smaller firm in a larger west coast city, methodically opened new offices, and its footprint now extends to the capital or the largest city in seven states. Prince Hal also absorbed a smaller firm in the same west coast city as the King, but except for two very small offices in other states has stayed local and (if my friends there will forgive me) sort of stagnated. It tried, but failed, to keep up with the King. Once the King was 25% ahead of Hal in lawyer headcount; now the King is 150% ahead of Hal.

Prince John, however, did not try to catch up with the King but kept its focus severely local. (It does have a few branch locations, all for specific articulated business purposes.) Within a few years Prince John outgrew Prince Hal in lawyer headcount and its practice thrives.

Which of the local royalty were better placed to defend against the invasion of Holland & Knight, K&L Gates, and Orrick? I’d vote for Prince John: as its competition tried to expand out of town, it doubled down on being the local hero.

Very well thought out and comprehensive “snapshot” of a major metro. Banks are always marquee clients, aren’t they? It sounds to me as if Prince John always knew who/what it was. The King, meanwhile, seems to have expanded its horizons notably (and at least as far as you report, is doing fine), but Prince Hal, I’m inferring, never made up its mind nor figured out who it wanted to be when it grew up. This isn’t necessarily a felony but I’m guessing the partnership has self-selected away from the ambitious and aspiring and towards the complacent happy with “the quiet life.” Not a tragedy! But a fascinating dynamic.

Thanks for this “case study!”

Bruce