Yes, I’m looking at you, law firm leaders. You, too, have a supply chain. It’s time to start thinking of it that way.

May we take a step back for a moment? From the redoubtable St. Louis Fed comes a study Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation During COVID-19 that puts some numbers and data around what we’ve all been living through. A few highlights:

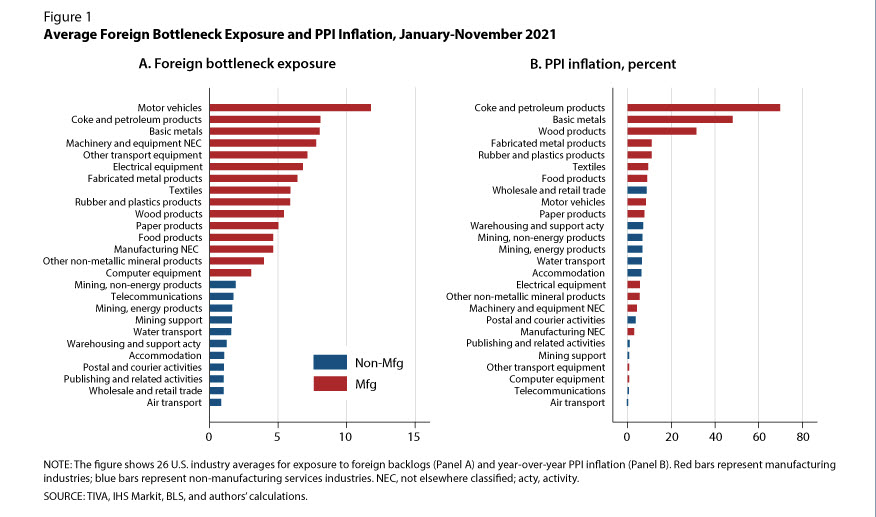

Producer price index (PPI) inflation—the change in input costs to producers—increased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this increase was heterogeneous across industries. The manufacturing sector was, on average, more severely hit than services. There was also large heterogeneity within the manufacturing sector itself: Coke and petroleum, basic metals, and wood products have seen the highest price increases, whereas computer equipment and other transport equipment experienced the lowest price increases (Figure 1). What factors contributed to the rapid increase in PPI inflation and the large industry heterogeneity? Authors Santacreu and LaBelle explore this question in detail in their 2022 article for the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review.1 This essay summarizes their main findings and examines the challenges ahead for supply chains and PPI inflation.

That’s their top-line takeaway, but permit me to interleave comments about how their next-level summary translate into Law Land:

The COVID-19 pandemic was characterized by a shift in the composition of consumption—away from services and toward durable goods [away from litigation and towards capital markets transactions, M&A, and private equity]. This is an important shift because the production of durables goods [capable midlevel associates] is organized into complex global value chains: Firms source necessary intermediate goods along different stages of production from around the world based on the comparative advantage of the source country. [Firms hire qualified mid- and senior-level associates from other firms in their metro area, in their region, in their country, or internationally if need be based on their “home firm’s” track record of training and professional development.] During COVID-19, the global nature of the crisis and subsequent government policies implemented worldwide to contain the spread of the virus (e.g., labor shortages, shipping crises, and lockdowns) made it difficult for firms to scale up production to meet the rapid increase in demand, leading to bottlenecks, long delivery times, and upward pressure on prices. [Because the unheard of spike in demand for deals was global and cross-border, the hunt for associates was also global and cross-border making foreign countries’ policies unusually important for firms used to hiring locally.]

A final visual and then we’ll move on before we press the analogy beyond the breaking point. This is meant to be enlightening and educational, but not necessarily to have a pointed moral lesson for Law Land:

You may be wondering what this graphic has to teach us–and I warned that it was more by way of background than pointed advuce–but it reaffirms a truism about supply chain breakdowns: They will not be universal; they will be local to markets or products or services (like highly capable mid-level corporate associates). That in turn means that to “solve” the supply chain meltdown of Covid you have to do something more than or besides hiring a bunch of mid-level corporate associates, even if you could find any. You need to think more expansively.

The problem with your supply chain, somewhat but not entirely analogous to that of major manufacturers with globe-spanning connections, is that it takes a long time to train a baby lawyer to reach the point of a capable mid-level associate. There is no way–no way–around this. (Consider the predicament of the global airline industry, which laid off, furloughed, and outright fired countless pilots during Covid; now that demand for travel has come roaring back, and then some, worldwide, they can’t scrape up enough pilots to put crews in all the flights people want to take. Same problem.)

I said there’s no way around this, and the most important consequence of this is that your chronic problem of mismatches between (client) demand and (lawyer) supply will be with us as far as the eye can see. You can’t “build the church for Easter,” as they say. Nor would it be prudent.

So what’s to be done?

The lateral associate hiring arms’ race seems to have exhausted itself very quickly. Associates are not stupid and one BigLaw is going to be pretty much like another BigLaw when it comes to what was causing their sky-high attrition: Too much work, too little communication, too much isolation, no social life and no personal life, the omnipresent Covid friction tax that made everything but everything more difficult, and so on. That string has been played out.

What else?

Developing or building out your own captive ALSP is a reality for a few firms, an option for more, and a pipe dream for most. (We’ve also expressed our own skepticism at how powerful and effective they can be as long as they’re under the aegis of the Mother Ship.)

And what else?

Back to manufacturers’ supply chains: When one source breaks down, hits their capacity ceiling, or suffers in quality and “on time delivery” (there’s another component of your business, by the way), you look elsewhere.

Like?

To the Big Four. Think of using them as excess capacity relief pressure valves for starters. And if it works and you get to know each other better, greener and greater and more ambitious partnerships may lie ahead.

Too novel? Unprecedented? Hardly anyone else is doing it? Yes, yes, yes. And that, my friends, is your competitive advantage. Steal this march.