Editor’s Note:

A modestly condensed version of this article was published a few weeks ago in Thomson Reuter’s Forum magazine. It was the leading story for a week after it was published.

We appreciate their courtesy in letting us republish a slightly longer version.

Bruce

According to Law.com, Bloomberg Law, The Financial Times, and pretty much any other name-brand media outlet you can shake a stick at, the story of the year for 2021 was associate attrition rates rising to all-time high levels—caused by punishing workloads—and firms’ countervailing efforts to combat it with whopping compensation increases.

Makes for a great story, with the bonus of a “Just So” moral coda: “Yet again, those at the top of the US economic pyramid get richer through thick and thin.”

But we noticed an uncomfortable disconnect: While the spectacular attrition rates and comp increases are real, the higher workload is nowhere to be seen in the available data. It gets worse. With apologies to F. Scott Fitzgerald, are you able to hold not two but three opposing ideas at the same time? They are:

- Thomson Reuters’ Peer Monitor Index (one of the most widely read and reliable datasets on key law firm statistics) shows, across all its firms, a decrease in average billable hours per month from 134 about 10 years ago to 124 lately (-7.5%). We may be working hard, but you didn’t hear this story when we were working even harder.

- As usual, “average” turnover masks a wide span of what actual firms are experiencing: Thirteen percentage points (about 40%) separates firms with the highest and lowest turnover. But/and (here’s the punch line):

- Comparing firms with the highest and lowest growth rates of compensation, associate attrition rates were…indistinguishable. And:

- The firms with higher billable hours had lower attrition.

I told you the data was weird.

But, as a beloved finance professor once told me, “Numbers don’t have opinions.” So if the data cannot be “weird” (it’s just an innocent bystander here), something must be wrong with our interpretation of the current situation.

First, we can drill down into the data a bit more than we have. A truism of statistics is that averages can mislead, and it turns out that counsel applies here.

Examining the most recent Peer Monitor Q4 2021 report (issued 14 Feb 2022), we find that “2021 closed out with incredibly strong performance on key metrics [and more specifically] a three-year high in Q4 demand growth,” up 4.2% over 2020’s Q4. Slicing the 4.2% average yet once more, “this growth has been driven almost exclusively by transactional practices,” with “corporate (all)” up 7.7% just by itself from the prior year (2020) and up a cumulative 10.2% from 2019. So here we have remarkable, almost explosive, growth. (7.7% as a compound annual growth rate produces doubling in less than a decade.)

Aside from the Peer Monitor dataset, we know from deep immersion in the industry that even “corporate (all)” understates the starkly concentrated composition of the Covid-era explosion in work for BigLaw: It’s all about massive pools of liquidity pouring into private equity, hedge funds, project finance, and strategic and financial M&A. From Manhattan to the City of London, the Middle East, Singapore, Greenwich CT, Silicon Valley, and beyond, investable cash is sluicing into the world’s capital markets and the buy-side asset holders are demanding it be put to work. Threatened central bank rate rises notwithstanding, it hasn’t slowed yet. And the burden of getting the deals done falls primarily on the shoulders of the partners and particularly the mid-level associates in the dozen or so truly elite financial powerhouse law firms with global reach. We have narrowed the pressurized hose from 4.2% overall demand growth to 7.7% corporate to the private-equity/M&A sector of corporate to that dozen or so law firms. No wonder associate attrition is at all-time highs.

And it really is; here your sense of what’s going on finds powerful confirmation in the numbers.

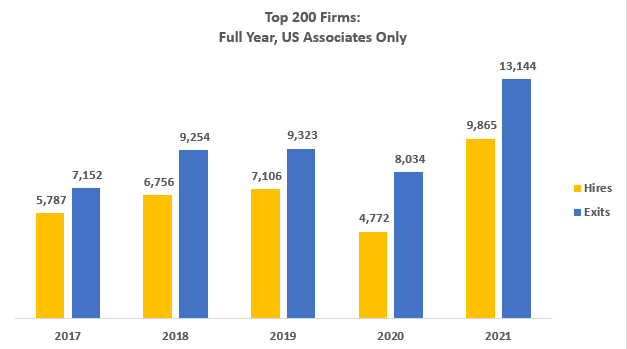

Leopard has the best data in the industry on lawyer movement and here are three charts that bring the story home.

First, the last five years of arrivals and departures (hires and exits) limited to US-based associates:

And second, “all lawyers” during a critical three month period late in the year:

We’re as fond of data as the next person, but enough already. This story began with a decades-high spike in associate workload coupled with a decades-high spike in associate comp, but if the second was supposed to ameliorate the first, it didn’t seem to be working. Firms with the heaviest workloads and those stingiest on comp were…retaining more associates, not fewer! What gives?[1]

We promised some thoughts, and we’d like to start with what’s been missing from this conversation until now: The human element.

Consider how the long dark Tunnel of Covid that humanity has been passing through for the past two+ years has overturned everyone’s lived experience. Not only did everything change overnight, Covid packed a witches’ brew of all that psychology teaches is most disorienting: It was unforeseeable, uncontrollable, mysterious, lethal, polarizing, and to top it all off, isolating. Humans crave shared experience, which was not to be had. Yet in our world of work, its burdens fell unevenly. Simply put, they fell heaviest on junior and mid-level associates.

Stress: We know a lack of control raises stress; autonomy eases it. Partners and senior associates had at least some, and for many a lot, of autonomy: Juniors less or none. It might be an exaggeration to say that in the Covid special case, stress is negatively correlated with seniority, but it’s a first approximation.

Isolation: Partners and senior associates in general have broader/wider/deeper personal networks, with luck more established and fuller personal lives, and almost certainly larger and more commodious homes. The stereotype is of the partner with a large home in Westchester or Connecticut, or a spacious apartment on the Upper East or West Sides (substitute Mayfair or Surrey): Breathing room, space, companionship, comfortable and attractive surroundings. But young associates? Perhaps a studio in a cookie-cutter white brick Manhattan high-rise (substitute the Barbican or East End). Social life and human interaction centered on the office, and it was yanked away with a still uncertain return date. Starbucks is no substitute.

Work intensity: Two points here. First, the more senior you are on a deal the more thoroughly you grasp the overall context and perspective: What’s the client trying to achieve, what are the opportunities and constraints, how does this component of the legal work fit in the overall picture, and so forth; this gives you a sense of control if not mastery. Juniors? “Give me a material adverse change clause favoring the buyer.” Huuuh? It can be mystifying and therefore unfulfilling.

Another subtler point: I will date myself by saying I remember spending hours in the library checking cases. Had to be done, and two Ivy League degrees were hardly required to pull it off, but it was 100% billable time and oddly soothing: A small period of repose and mindless behavior in an intense day. Technology—God bless it—has taken that away. There are no grace periods in an associate’s day when you can shift the mind to neutral and still get full credit for what you’re doing. Hit “cite-check” on the toolbar and you’re done. Ten hours then and ten hours now are not the same, and now is a lot more relentlessly demanding.

No boundaries: During Covid, “work” and “life” boundaries have melted away: The two blend and mix. While this may sound like a magical, liberating realm to occupy—“flexibility!” “autonomy!” “flow!”—the exhausting reality is that without boundaries you begin to feel that you’re always working and always cooking, cleaning, caring for children and dogs, getting things out and putting things away, in a ceaseless loop.

You’re on a 24-hour clock, not an 8/16 or 12/12 one. The toddler wandering through the background on “Zoom” is amusing the first time or two and then not at all, and loading the dishwasher while on a conference call is going to lead to humiliation in assured due course.

A friend whose mother worked in an office in an era when almost no mothers did reported asking her, with the guileless naivete of childhood, “Why do you work, Mommy?” Her reply, “It gives me two perfect moments every day: When I leave in the morning and close the front door behind me, and when I return in the evening and open the door.” Boundaries. Without them we’re frazzled, half-attentive, distracted; it feels as if we’re struggling against constant friction and resistance just to get from waking to sleeping. (Did we mention the copious research proving that “multitasking” is a sadistic concept?)

It’s not about the $$: People aren’t motivated by money; not at this level anyway—certainly not those you want to have working at your firm. “Pay” is consistently somewhere between fifth and tenth when people are asked what they value about their work. Well ahead come autonomy, satisfaction at a job well done or a client well served, the camaraderie of colleagues, intellectual challenge and personal growth, seeing the firm thrive, gaining the respect of peers, solving problems, embodying high standards, achieving mastery.

Leaders have a powerful impact, beyond what they may know, on those very tangible “intangibles.”.

If you care about the future of your firm, which depends on the caliber of talent you can offer, you need to define, articulate, and preach ‘til you’re blue in the face, compelling answers to these questions:

- What “secret sauce” do we provide clients that other firms just can’t?

- What are we building here?

- What does this firm stand for?

- How can we leave this place better than we found it?

Insipid, boilerplate, or unconvincing answers will repel everyone—and no amount of money will make them stay. Yes, of course pay “the going rate.” You should, you must, there’s nothing more to say. But also give them something of far greater value. Inspiring answers to those questions will motivate people to put up with a lot. The magisterial oral historian of work, Studs Terkel, condensed it brilliantly:

“Work is about a search for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

People don’t just yearn for that, they need it. Or else.

[1] If you’re thinking of tacking course at your firm to flog the associates harder and institute pay cuts, we are on the record as stating that we do not recommend it.