Two plus years after the simultaneous worldwide Office Exodus (“Everybody out of the building!”) at the onset of this pandemic, we are at last beginning to emerge from the by-guess-and-by-golly finger-in-the-air period of figuring out what WFH (thank you, Zoom, Webex, Teams, Slack, etc.) means for the cost, and the value, of the immense stocks of commercial office buildings in major cities’ downtown centers.

A note on context:

One of the classic forms of market failure stems from information asymmetry: Buyers know more than sellers (in general, or about a specific item or service) or vice versa. In this case, knowledge is power–the power to be a superior judge of the right (most accurate) price. Various states’ “lemon laws” addressing used cars’ crash maintenance histories are motivated by the well-intentioned desire to address this. And, essentially, the entire edifice of US securities laws are designed to thwart, or cure, this form of market failure.

When it comes to information asymmetry, it’s safe to say that by and large it works to law firms’ advantage. Well-placed law firms should be hotbeds of network connections, deep expertise, and intense pockets of talent trading in knowing what vothers may not know. But for a long time, commercial real estate players and landlords held the high cards when it came to pricing big ticket and long duration office leases. As the authors of the study we’re about to discuss write,

In comparison to other real estate markets, for instance in residential real estate, the market for commercial office buildings is comparatively opaque. We combine data from both public and private markets in order to make progress in understanding valuation of the entire sector in light of disruptions introduced by the coronavirus pandemic and remote work.

And so I introduce a “level the playing field” tool: At last we have an economic study of this high-priced and long-term component of law firms’ operating expense, and not just any study. This comes from three highly credentialed professors of economics right here in New York.

Rather than paraphrase, permit me to share the abstract in haec verba:

Work From Home and the Office Real Estate Apocalypse

69 Pages Posted: 9 Jun 2022

Date Written: May 31, 2022

Abstract

We study the impact of remote work on the commercial office sector. We document large shifts in lease revenues, office occupancy, lease renewal rates, lease durations, and market rents as firms shifted to remote work in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. We show that the pandemic has had large effects on both current and expected future cash flows for office buildings. Remote work also changes the risk premium on office real estate. We revalue the stock of New York City commercial office buildings taking into account pandemic-induced cash flow and discount rate effects. We find a 32% decline in office values in 2020 and 28% in the longer-run, the latter representing a $500 billion value destruction. Higher quality office buildings were somewhat buffered against these trends due to a flight to quality, while lower quality office buildings see much more dramatic swings. These valuation changes have repercussions for local public finances and financial sector stability.

The value of the NYC office properties in our dataset is $175 billion. The short-term value reduction of 33% amounts to $57.7 billion, the longerterm reduction of 28% amounts to $49 billion. Extrapolating to all properties in the U.S. in our dataset, the $72 billion annual leasing revenue results in a $631 billion office value before the pandemic using the same 8.76 value/lease revenue ratio. [Editor’s note: This ratio seems to be an historically derived empirical estimate.–Bruce] We estimate that pandemic-related disruptions around remote work have lowered the value of office buildings observed in our dataset by $208 billion in the short run (33%) and by $177 billion in the long-run This number is very close to the $172.3 billion estimate in an October 2021 report New York State Comptroller’s office. These estimates understate the value destruction of the overall U.S. office stock since our data do not cover the universe of commercial leases. We underestimate lease revenues by a factor of about 2.8. The total decline in commercial office valuation might be, as a consequence, around $586 billion in the short-run and $498 billion in the long-run.

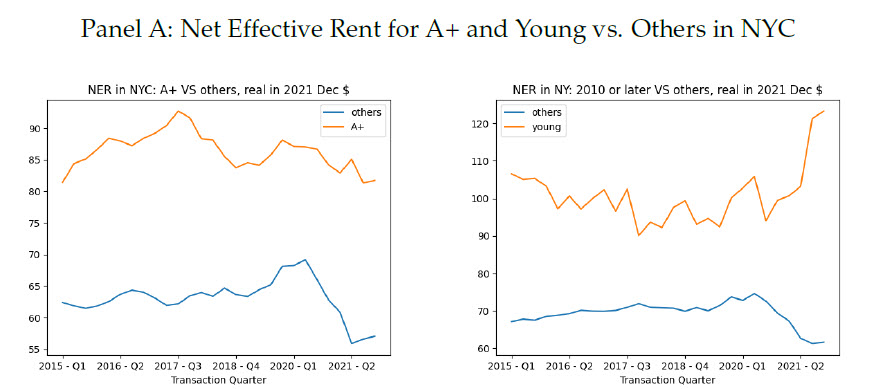

We observe even stronger evidence for differing trends across office space by quality in Figure 2, which focuses on New York City and Texas, as representative examples of both major and non-major commercial real estate markets. Panels A and B display changes in net effective rents per sf on newly-signed leases for properties. The left panels define A+ properties as before. The right panels entertain an alternative definition based on building age to identify trends in rents across building quality: younger buildings are those constructed in or after 2010. Properties defined as A+ sustain rent levels much better in both New York and Texas compared to other properties. Younger buildings even experience sizable rent increases, compared to substantial rent decreases for other properties. This divergence suggests a “flight to quality” in office demand in these markets.

- A drastic decrease in net square footage leased–down by nearly 70% from the prepandemic baseline at barely one-third of the (say) 2019 demand level; and

- A dramatic decrease in lease duration. Pre-pandemic, most major commercial leases extended for at least seven years, and very few had terms of three years or less. That pattern has inverted. New leases of shorter than three years “increased substantially to account for almost half of our sample,” while those over seven years decreased “meaningfully,” which foretells that in the 2023–2025 window, expected lease expirations should spike both because of the baked-in expiration of long-term pre-pandemic leases and the expiration of Pandemic Era short-term leases.

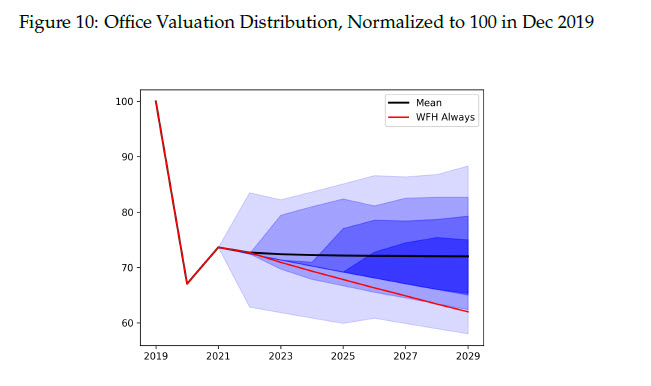

May I summarize the learning from this in plain English? If you need to renew a major office lease at your firm, hold your fire. Shall we go to the graphic?

The graph illustrates a mean path that sees no recovery. Remote work is a permanent shock. Ten years after the transition, office values remain at levels that are about 28% below the valuation in 2019. (Emphasis supplied.)