In our first installment of this two-part series, we left off by asking why the composition of the Fortune 500 across a quarter-century span, from 1995 to 2020—widely thought of as an era of widespread disruption for major corporations—had actually been remarkably stable. If you had a chance to read that column, you know the answer to this question: How many Fortune 500 companies as of 2020 were born after 1995? 100? 50? 25? The actual answer is 17. That’s all.

Evidently incumbents are quite gifted at responding to disruption. How do they do it?

How Incumbents Survive and Thrive (HBR, January/February 2022 issue) presents one set of compelling answers to this.

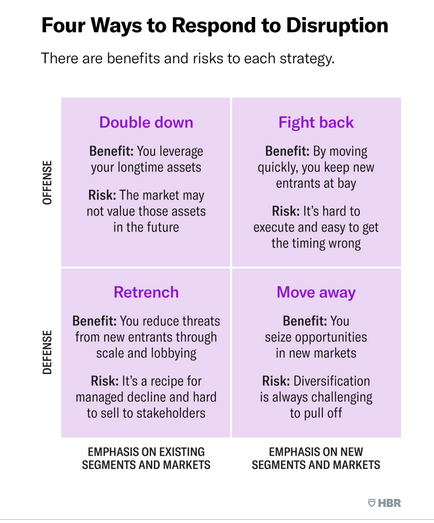

The instinctive response of many companies to a threatening interloper is to mount a frontal assault, “fighting fire with fire,” launching a competing division, building an Incubator or skunkworks accelerator. But at least three other, often more prudent, options are available and I commend them to you for your consideration. Beating the newbie at their own game can be a financial and talent sinkhole. (Microsoft’s “Bing” challenge to Google was all but DOA, and have you ever heard of GM’s “Maven,” an Uber wannabe?)

Double down

For 15—20 years, Disney refrained from taking on the streaming services and instead bulked up on services it owned, adding Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, and exercising the bargaining power latent in its blockbuster (no pun) back list with Netflix and others. Only when streaming was truly mainstream and Disney comfortable behind its content-is-king fortress did Disney+ appear.

Retrench

By and large this entails consolidating with existing incumbents to build market share, or going to the powers-that-be regulators to lobby for constraints and shackles to be imposed on troublesome newcomers.

Migrate away

Kodak could have—and Fujifilm did—morph into an imaging and high-end healthcare hardware firm, rather than remain stuck on milking every last drop of blood from B2C film. Thomson (Canada) sold off its newspapers before they were worthless and merged with Reuters to become a largely B2B data subscription and original content provider.

Here’s an intuitive way to think about it:

Amusingly, we have seen incumbents hop from one of these approaches to another as expedience demands. JPMorgan responded to cryptocurrency by loudly denouncing it and joining a consortium of banks to investigate it, then (later) invested in it directly. Fiat Chrysler’s response to EV’s and autonomous vehicles was even more baroque: It partnered with newcomers Waymo and Aurora, while at the same time forming an alliance with BMW, Intel, and Mobileye—and not to be outdone, also went full-bore for a merger with France’s PSA (Peugeot/Citroen/DS/Vauxhall/Opel, now going by the name “Stellantis,” for which some fortunate branding firm no doubt collected an ungodly fee).

As the authors characterize this charitably, “In conditions of high ambiguity, hedging your bets makes sense.”

Well, yes but. What ultimately got Kodak was not that they didn’t know about digital photography (they held the first US patent on it!), but that under a succession of CEO’s they dithered with a little of this and a little of that for years until they predictably ran out of cash.

Back to statics vs. dynamics.

The point is not really about that 2 x 2 matrix and “where” you should go. The point is about how your firm can remain on its toes so that new entrants can barely touch you. In “Adaptability: The New Competitive Advantage,” (all the way back from 2011), the authors drive this point home (emphasis supplied):

Think about it. The goal of most strategies is to build an enduring (and implicitly static) competitive advantage by establishing clever market positioning (dominant scale or an attractive niche) or assembling the right capabilities and competencies for making or delivering an offering (doing what the company does well). Companies undertake periodic strategy reviews and set direction and organizational structure on the basis of an analysis of their industry and some forecast of how it will evolve.

But given the new level of uncertainty, many companies are starting to ask how their strategic planning can continue to be (a) baseline germane in analyzing the fast-moving environment, and better (b) provide pointed insights into where the firm should be positioning itself in the nearer and longer term.

Here’s the coda:

The answers these companies are coming up with point in a consistent direction. Sustainable competitive advantage no longer arises exclusively from position, scale, and first-order capabilities in producing or delivering an offering. All those are essentially static. So where does it come from? Increasingly, managers are finding that it stems from the “second-order” organizational capabilities that foster rapid adaptation. Instead of being really good at doing some particular thing, companies must be really good at learning how to do new things.

Those that thrive are quick to read and act on signals of change. They have worked out how to experiment rapidly, frequently, and economically—not only with products and services but also with business models, processes, and strategies. They have built up skills in managing complex multistakeholder systems in an increasingly interconnected world. Perhaps most important, they have learned to unlock their greatest resources—the people who work for them.

This may sound all too familiar, but focus on what the authors are actually saying. After a somewhat extended and thoughtful dive into what what happens to companies that fail to meet the test of being “adaptable,” they conclude that “sustainable competitive advantage” no longer consists–as it long did–in the “static” characteristics of “position, scale, and … delivering an offering.”

So what has replaced those familiar hallmarks of success? Nothing other than thinking in dynamic analysis terms. Doing that—and applying that thinking—is, they assert, a core organizational capability.

It cannot be delegated to a “task force” or to a strategic planning department. Operating dynamically has to be something your firm lives and breathes throughout the entire organizational structure. And you must embrace a high and sustained level of curiosity: Think of it as your own horizon-scanning radar. Rest on your entrenched position and turn off that over-the-horizon vision at your peril. You are in this for the long run, aren’t you?