That phrase has become almost too famous for its own good. Or, at least, far too widely and thoughtlessly invoked. A few years before his too-young-too-soon death, Christensen and two colleagues published a corrective to the lazy abuse of the phrase, “What Is Disruptive Innovation?” (HBR, December 2015). He gets back to the core concept and reaffirms its power if used in the classic and pure sense:

First, a quick recap of the idea: “Disruption” describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price. Incumbents, chasing higher profitability in more-demanding segments, tend not to respond vigorously. Entrants then move upmarket, delivering the performance that incumbents’ mainstream customers require, while preserving the advantages that drove their early success. When mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume, disruption has occurred.

Latent within Christensen’s stricter description is that disruption is a process, not a snapshot of a moment in time. He uses the example of Netflix when it was just getting started in 1997. Blockbuster customers were concentrated among those who wanted to rent new releases more or less on impulse, which Netflix’s (then) DVD-through-the-mail model did not serve. Blockbuster was right to ignore Netflix at the time: Put more strictly, Blockbuster was right not to immediately turn its business model upside down to cater to the tiny minority of customers in the market who preferred the Netflix approach.

Buried within this “different market/different customer base” phase is an integral component of disruption classically understood. In its early years, Netflix was not poaching Blockbuster’s core user group; it was nibbling at a fringe Blockbuster was comfortably able to ignore.

The problem (Blockbuster’s, not Netflix’s!) arose when Netflix strategically capitalized on new technological developments—specifically, widely distributed and affordable broadband and advances in the quality and reliability of streaming video—to attack Blockbuster’s core. And that was when Blockbuster did not or could not respond. Christensen & Co. don’t fool themselves that this is easy (emphasis supplied):

Incumbent companies do need to respond to disruption if it’s occurring, but they should not overreact by dismantling a still-profitable business.* Instead, they should continue to strengthen relationships with core customers by investing in sustaining innovations. In addition, they can create a new division focused solely on the growth opportunities that arise from the disruption. Our research suggests that the success of this new enterprise depends in large part on keeping it separate from the core business. That means that for some time, incumbents will find themselves managing two very different operations.**

Of course, as the disruptive stand-alone business grows, it may eventually steal customers from the core. But corporate leaders should not try to solve this problem before it is a problem.

[…]

The theory of disruption predicts that when an entrant tackles incumbent competitors head-on, offering better products or services, the incumbents will accelerate their innovations to defend their business. Either they will beat back the entrant by offering even better services or products at comparable prices, or one of them will acquire the entrant. The data supports the theory’s prediction that entrants pursuing a sustaining strategy for a stand-alone business will face steep odds: In Christensen’s seminal study of the disk drive industry, only 6% of sustaining entrants managed to succeed.

_________________

*This is the perennial refrain of the incumbent partnership of a law firm, but we would suggest, with the obligatory respect, that this is not the end of the spectrum that law firms will need to protect against. Overwhelming force will back up this view—“don’t overreact.” What law firms need to beware of is complacency.

**Captive ALSP’s, NewLaw-ish hackathons, etc. will not be given oxygen if they’re at a firm’s HQ location or under the umbrella of any other major office. Unless you establish the strictest and most impenetrable of Chinese walls.

This brings us to the final HBR article bookending this discussion of statics vs. dynamics, from the January/February 2022 issue: “How Incumbents Survive and Thrive.”

Surely the perspective of this article—that disruption is not what it’s cracked up to be—is strikingly contrarian to today’s common wisdom. Are the authors right, or (forgive me, HBR) is this just the intellectual cheap trick of playing “devil’s advocate,” a sort of high-minded second cousin to clickbait?

Our strong natural preference is to start with data, and fortunately this article provides quite a bit.

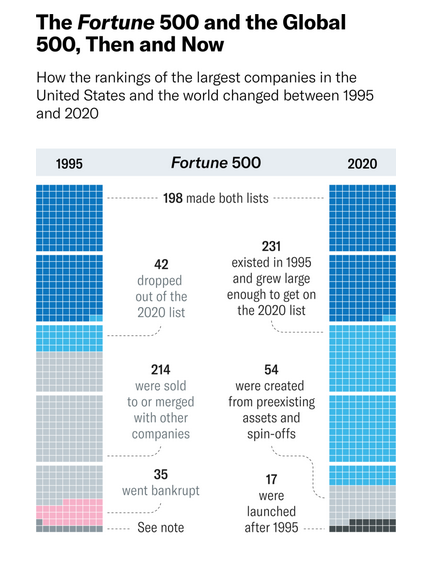

Let’s stipulate that the online revolution began around the mid 1990’s, say 25 years ago. Guess how many of today’s Fortune 500 companies did not exist in 1995? Seventeen. The other 483 (96.4%) existed in one way or another 25 years ago. Here’s the exact breakdown:

- 198 (39.4%) of the Fortune 500 in 1995 still made the list in 2020;

- 35 (7%) went bankrupt by 2020;

- 231 (46.2%) were going concerns in 1995 that grew enough to make the 2020 “500;”

- 256 (51%) of the 1995 group dropped off because they didn’t grow enough to still qualify, were merged or acquired, or simply grew too slowly to continue to qualify.

- And only 17, but yes, including high-profile newcomers like Tesla, Facebook, Google, Netflix, and Uber, were truly brand new.

For those of you who have a reflex reaction to refer to the footnotes, the somewhat cryptic “see note” tagging 11 firms at the bottom of the 1995 list refers to “duplicates” (!?), foreign-owned, and “a few companies that could not be traced because of name changes.” (?!?!)

Can we say anything meaningful about industry sector differences? Not surprisingly, yes: TMT (technology, media, and telecom) saw the greatest proportion of failures and new arrivals, with hotels and restaurants second, and:

The other sectors—energy, materials, and chemicals; industrials, automotive, and aerospace; consumer products; health care and pharmaceuticals; transportation and travel; and even financial services and insurance—all had high levels of inertia and look surprisingly stable.

If things have been so surprisingly stable, why?

For that, you’ll have to read the next installment of this series, which gets deeper into “planning for the unknowable,” and why a dynamic and not a static mindset is indispensable.

See you then!