If you’re like me, you may be troubled at the thought of all that you do not know or understand about China. And, if you realize the depth of your ignorance on something so important, you ask the smartest people you know about That Something what you should read on the topic to get smarter.

So it was that I turned to a very special and long-time friend who is, among his many other outstanding qualities:

- natively bilingual in English and Chinese;

- Harvard/Columbia Law;

- former chair of the San Francisco Fed;

- and the managing partner for Asia of an AmLaw 50.

My friend David gave me a short list of five books, from which I chose David Shambaugh’s China’s Leaders: From Mao to Now (2021). Shambaugh is a widely acclaimed expert on contemporary China and international relations within Asia and is Director of the China Policy Program at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. His previous books on China, as author or editor, number 28.

True to its title, the volume consists of introductory and concluding chapters bookending five chapters, one each on:

- Mao Zedong–short-handed by Shambaugh a “populist tyrant”

- Den Xiaoping, “pragmatic Leninist”

- Jian Zemin, “bureaucratic politician”

- Hu Jintao, “technocratic apparatchik”

- and Xi Jinping, “modern emperor”

One can argue with the author’s organizing principle for covering the history of “modern day” (CCP-controlled, 1949– ) by pegging it to the hook of the five most consequential and long-lasting leaders of the PRC over its first seven decades, but it’s an accessible point of entry to an audience such as I might represent: Super-non-expert, that is. Shambaugh begins by disabusing the reader of any notion they might entertain that this has been 70 years of continuity or linear progression–“there has been a considerable degree of discontinuity. [emphasis original].”

To be sure, all have had to confront the realities of China as a nation, an economy, and a society/culture in the second half of the 20th Century and the 21st as far as it has unfolded. These include:

- a priority placed on “self-strengthening” China economically and otherwise (true actually since the late Qing dynasty ca. 1870s–1890’s)

- recovering lost dignity and respect, reinforcing its territorial integrity and sovereignty;

- reducing poverty and social inequality;

- increasing educational levels in general and literacy rates in particular;

- and perhaps nearest and dearest to my heart and head, striking a delicate and ever-shifting entente cordiale between free markets and robust private enterprise vs. drawing and enforcing strong and unforgiving lines around political and individual freedoms, including of worship, expression, assembly, and petition.

Because each of the five leaders was so different, and ordered their priorities with such great variety, I cannot do better than to paraphrase and summarize Shambaugh’s own conclusions in his final chapter. I borrow liberally from his words as he is by and large a clear and forceful, it unpoetic, writer (see From Mao to Now at Chapter 7 pp. 318–339).

Mao Zedong was extraordinarily complex and the hardest by far to encapsulate. He was free of any consistent style, although a powerful enduring theme was his intrinsic populist faith in “the masses” and corresponding distrust of and hostility towards institutions. Hence all his multiple “campaigns,” some of historic cruelty, scope, and scale in terms of death and suffering. (Shambaugh estimates the total deaths over his successive campaigns of coercion as “conservatively” 40-50 million.) Yet he also joined “the dynastic pantheon of China’s emperors” by virtue of his being in word and deed the founding father of modern China: Standing atop Tiananmen Gate on October 1, 1949 and proclaiming the birth of the PRC.

He ruled in many ways imperially and “behind the curtain,” ceasing to even attend Politburo or Central Committee meetings after 1959 and ruling through cryptic four or eight-character idioms taken from classical Chinese texts (or of his own creation), issued from an inner sanctum well within the Forbidden City. He was contradictory to a fault: Becoming an intent student of Chinese history with an intense disdain for intellectuals; fascinated by the outside world and foreign relations but only leaving China twice in his life (both times to the Soviet Union).

He single-handedly forged the Sino-Soviet alliance and then fathered its breakup; chose to enter the brutal Korean War; initiated efforts to reach out to President Nixon; and launched the (1973) “Four Modernizations” program to open relations with the West.

In short, modern China would be unimaginable without Mao; but Mao would be almost equally unimaginable as a leader of China today.

Deng Xiaoping had a tough act to follow.

Typically, the immediate successor to a first-generation Creator is a somewhat toothless and short-lived caretaker. (Stalin, after Lenin, and Chiang Kai-shek, after Sun Yat-sen) were exceptions since both Founder/Creators had exceptionally short tenures at the head of their newly created nations.

Deng was far more than a passive successor to Mao; he is often seen as the anti-Mao, which is true if you look at all the pragmatic reforms he undertook that repealed, reversed, and destroyed much of what Mao had done. (As another contrast, he had zero charisma and never ruled by charm, although he did gain and earn stature.) He lived an anti-imperial life, moving out of the Forbidden City altogether for a modest house on a lake just to the north. He was frugal, loyal and faithful to his wife of many years (you can connect the anti-dots to Mao), traveled widely abroad (first at age 16), felt a certain envy towards the West–which Mao disdained if he didn’t loathe–and with the exception of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, was seen as largely pacific and tolerant.

Deng’s most oft-quoted saying, which encapsulates his opening towards private property and private enterprise, says much: “It doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.”

Jian Zemin’s main claim to fame may be his surmounting the international isolation following the Tiananmen massacre on June 4, 1989, presiding over Britain’s return of Hong Kong to the PRC, and been the first “modern” (Communist era) Chinese leader to preside over a sustained period of economic growth and rising prosperity. Of him, little was expected but much was delivered:

Jiang ‘grew into’ the role and gained confidence over time–stepping down only when mandatory retirement kicked in.

Personally and stylistically, he was also far more extroverted and even exuberant than Mao or Deng, “very animated in meetings, physically gesticulating frequently, talking incessantly, and regularly veering off-topic.”

Be that as it may, it’s difficult to recall any enduring contribution he made to modern China, even to deeply immersed experts like Shambaugh.

Hu Jintao was more the cipher and caretaker.

Although he had a decade as heir apparent to use touring the nation and making himself and his priorities will known, “he did not use this time effectively.” His speeches were “perfunctory,” and his decade of apprenticeship were innocent of exposure to genuine domestic or foreign policy issues. The result was predictable:

“Hu’s decade of rule [2002–2012] is generally seen as unremarkable. His lack of preparation, his own sterile personality, and little constituency-build during the previous decade m have had something to do with it but but the end, many Chinese referred to this period as the ‘ten lost years.'”

Before we get to Xi Jinping….

An interlude providing some data on China.

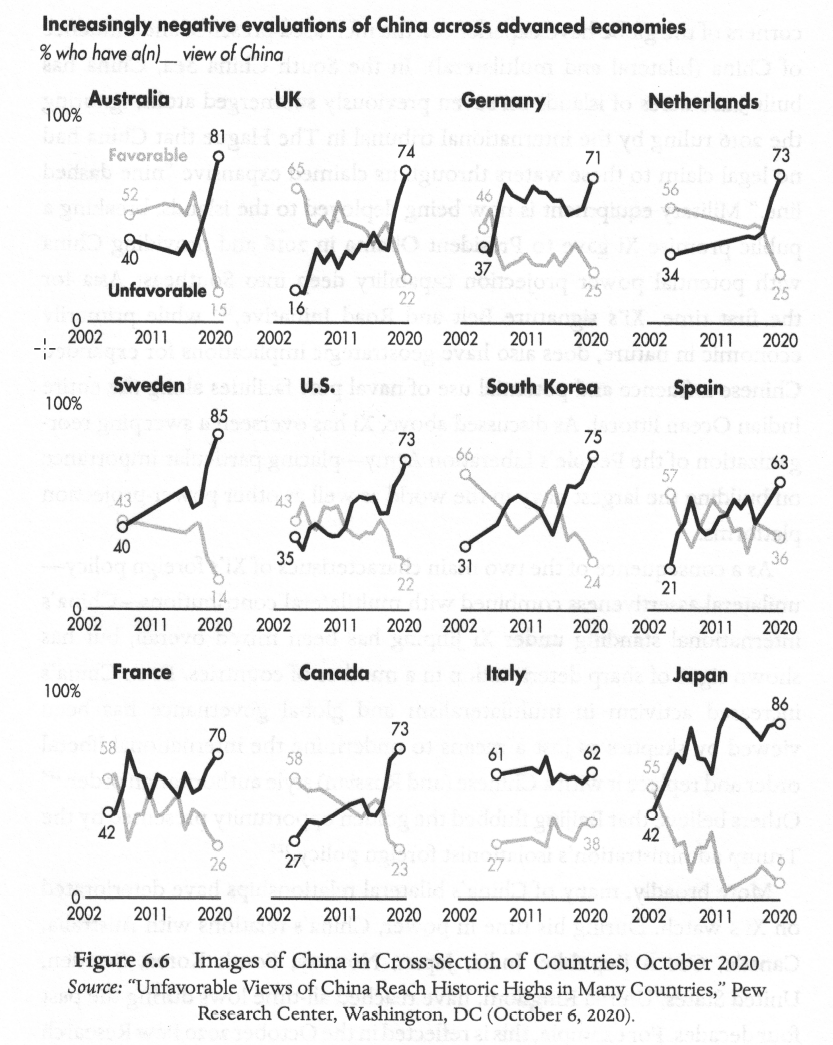

First, an extremely illuminating, and rather unexpected to me, sample of public polling across a dozen countries (“advanced economies”) showing the change in “unfavorable views of China” across the last 20 years. This image appears in Shambaugh’s book at p. 312 and is credited to the Pew Research Center (Washington, DC) as of October 6, 2020:

Provides a consistent pattern, eh what? Of particular interest to me–I wonder if you read the charts the same way–was that the growing negativity towards China predated Covid-19, and to my eye (OK, the data series may have ended too “early” to draw any definitive conclusions here) there is no change in the trend lines coincident with the arrival of that dratted pox. If this holds true as the data series continues into our futures, it would be a relief to see and a win for rationality.

Second, a few somewhat arbitrarily selected excerpts from Chapter 1 of Shambaugh, “On China’s Leaders and Leadership.” This comes from a section called “The Influences of Chinese Political Culture,” which correctly points out that while the CCP leaders are “communist (Marxist-Leninist) in their orientation,” “they are also Chinese leaders and are thus deeply shaped by historical and culture traditions of politics and rule” (emphasis original).

I leave it to you, dear Reader (as is our custom here) to draw your own conclusions, but here is a summarized, lightly edited/paraphrased, and shortened list of “a number of the most salient residual elements and built-in assumptions from Chinese historical political culture that have continued to influence post-1949 CCP leaders,” in Shambaugh’s view (pp. 12-13):

Leaders should inherently be benevolent, and set a moral example.

But coercion against usurpers is justified to maintain the sanctity of the regime.

The physical core of China is ethnically Han; other groups on the periphery or farther away are “outsiders” or “barbarians.”

Other powers are predatory and seek to take advantage of China; they are not to be trusted.

China is a great global power with over 3,000 years of history; restoring China’s global status as a respected great power is the primary mission of all Chinese leaders.

To the greatest extent possible, China must remain autonomous and self-reliant; (inter)depending on others is a recipe for manipulation.

Disorder is to be avoided at all costs and a premium is to be placed on stability.

Maintenance of “face” and avoiding embarrassment is essential not only within Chinese society but with foreigners; the appearance of confidence and grandeur are paramount.

The Chinese people are a “loose sheet of sand” who need to be led by the tutelage of enlightened elites.

This brings us to Xi Jinping.

Xi Jinping has put his stamp on the nation and the world as has no Chinese leader since Mao; his reign is “neo-totalitarian” and, using the full power of technology, rests on an unprecedented surveillance state. “He is fixated on power–his own and his country’s.” (p. 336). The process began with a sweeping purge of potential enemies, to the point (today) that the “sycophancy surrounding Xi has not been seen since the Mao era.” Xi is “an emperor-like figure” but he remains “divisive” within China particularly among many urbanites, intellectuals, and Party members resenting the state’s strict controls and “draconian repression.”

Nevertheless, he has “certainly been a transformational leader,” exerting an “extraordinary impact,” exuding personal confidence and an air of entitlement and destiny and, barring a sudden coup, is likely to remain in power for some time. Despite “ample precedent in Chinese politics” for a sudden purge from power, “autocrats the world over have demonstrated a stubborn tenacity for sustained rule through repression and populism.”

Thus must we leave this survey of nearly 75 years of Chinese CCP rule an unfinished story. As Shambaugh concludes (p. 339): “Time will tell with Xi Jinping.”

Two additional thoughts bearing no connection whatsoever to the book:

(1) Without fear of contradiction, we can assert that Xi Jinping is now “emperor” for life, or for as long as he cares to wear the mantle. Historically, this has been thoroughly the norm for leaders, but since about 1945, if not 1918, it has been the exception for leaders of globally consequential nations. We shall see whether the old model or the new is superior, or certainly how they interoperate simultaneously.

(2) The question at the forefront for financial markets, for some time now, has been whether China is “investable.” On the one hand, it’s the second largest economy in the world (by GDP) and unquestionably brings new meaning to the word “vibrant.” On the other hand, the CCP remains unquestioned arbiter of all that goes on in the nation, in terms of development, investment, trade, R&D, infrastructure, and you-name-it. If the plug could be pulled on (say) Evergrand in a heartbeat, what sane investor would risk their capital on opaque caprice?

Goldman Sachs published a monograph on this very topic just a few weeks ago. For those (including yours truly) interested in delving further into such topics, here’s the executive summary of the 36 page report:

As the Chinese government continues to carry out unprecedented regulatory tightening, what the new regulatory environment means for China’s growth, investment outlook and beyond is Top of Mind. We get perspectives from Primavera Capital’s Fred Hu, Oxford University’s George Magnus, Tsinghua University’s David Li and CSIS’s Jude Blanchette, and our own economists and strategists. Hu, Li and our analysts view these shifts as largely consistent with the goal of achieving sustainable and socially responsible growth, suggesting limited damage to China’s longer-term growth and investment prospects, despite the likelihood of continued market volatility and a growth drag over the shorter term. But Magnus and Blanchette see strong political motivations at work, especially in the run-up to next year’s important 20th Party Congress, and are more concerned about the longer-term growth and investing implications. That said, we find little evidence of spillover effects beyond China from these shifts so far, with EM assets remaining resilient, and expect this to largely continue.

It strikes me that the risks to heavyweight investors in China (blessedly not a problem I have to solve first-hand) is that the unknowns do not fall within any manageable or calculable boundaries. Let me explain: If you believe, as every sane or at least mainstream investor does these days, that the Fed is in the process of “tapering” and that sooner or later it will begin to raise rates, the unknowns are (a) when; (b) how much; and (c) how fast. There is zero risk that the Fed will announce that it’s abandoning all support for the US economy (say) or raising rates to 21.5% effective immediately. But the risks to investors in China are virtually boundless because the government can do whatever it wants whenever it wants. (See, e.g., the Didi IPO imbroglio.)

Caveat emptor, big time.

Separately, I will leave you with what I heard in the form of a very different view of what’s going on in HK which presents a vivid contrast of what we consume through the MSM. This from a long-time Anglo correspondent/friend who’s a partner at Name Brand Firm:

I have been grounded in HK since March 2020 at my duty station. I have just returned to the West Coast to attend a [meeting] and to see my wife and children. I will be flying back to HK [soon]. With great regret, I must report that the coverage by NYT and WSJ of HK has bordered on the irresponsible. Both have had headlines of “death knell of HK”. HK remains a global financial center with historic amounts of capital and investment pouring in and the global banks doubling their employment in HK. I wonder if these reporters will feel any embarrassment in 3 years when HK is an even stronger financial center than it is today. Forgive me, but these “news” articles have been the bane of businesses in HK, all of which are forging ahead at full speed, including the law firms.

This observation confirms my view of the MSM dating back to about my college or even high school days. To wit: “Everything you read in the WSJ, the NYT (etc.*) is the gospel truth with the rare exception of matters you know deeply and personally, which are flagrantly mischaracterized to the point of unrecognizability.”

This presents a nearly irreconcilable dilemma when reading the MSM, of course. As with investment portfolios, my imperfect but tolerable workaround is “diversification” [of sources]. The result remains innately dissatisfying.

______

* Additional media which could be listed according to taste would include the FT, the Economist, PBS, the BBC, Bloomberg, the Washington Post, CNN, and any other MainStream outlet whose reputation was not built first-foremost-and-always on being head-snappingly partisan about everything all the time and extremely so.