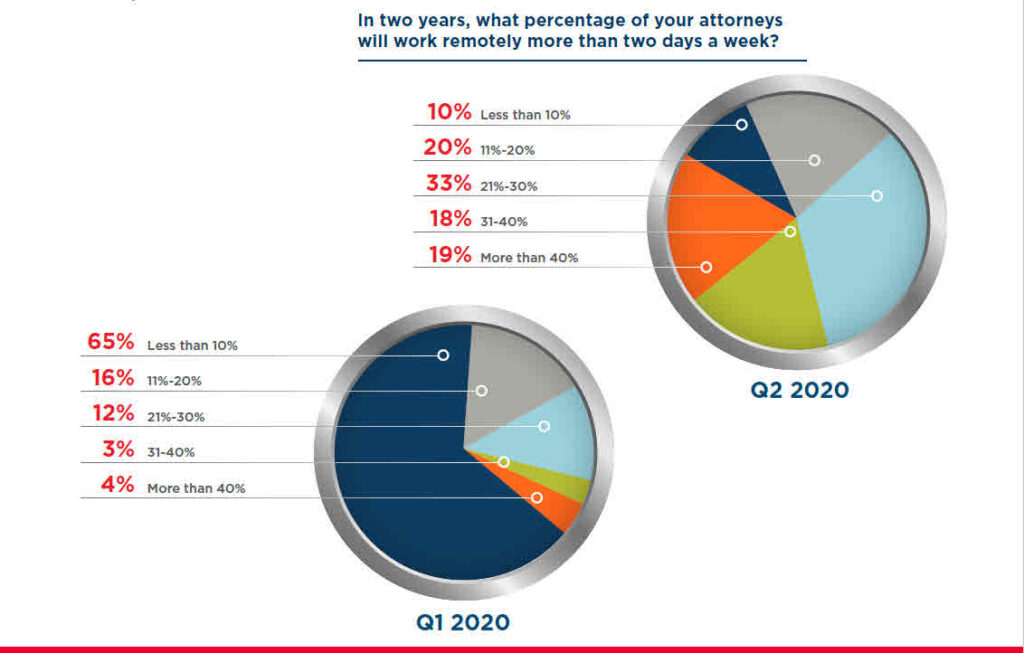

Here’s one of the most dramatic visualizations I’ve seen of how quickly BigLaw attitudes changed towards remote working. Note that this is the same question asked of (basically) the same people in January through March of last year and again in April through June:

It speaks for itself, but some of the drastic changes demand highlighting: In terms of the percentage of lawyers working remotely “more than two days a week” (which sounds like more than half the time to me):

- >40% quintupled

- <10% shrank by 85%

- And more than one-third quintupled from 7% to nearly 40%

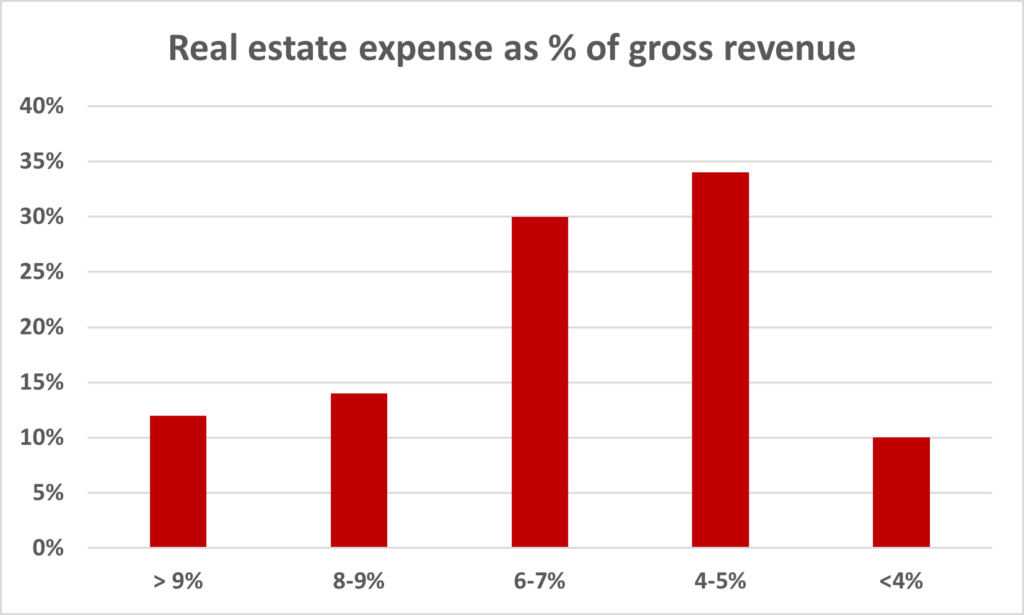

Earlier I mentioned that lore in our data-drought-stricken industry is to the effect that real estate is the second largest category of expense. Well, Law Land may exist on a barren Martian-surface data landscape, but the commercial real estate industry does not. Here’s what the Cushman & Wakefield survey reports about law firms’ spend on real estate as a percentage of their annual gross revenue:

This does not give us an industry average—and it would be surprising to the point of incredible if firms clustered much more tightly on this metric—but it gives us a compass point to estimate with. Eyeballing this distribution I’m going to make the assumption for purposes of the rest of this column that the “average” industry-wide is 6% of annual gross revenue going to real estate. The gross revenue of the 2020 AmLaw 200 was $124.6-billion, so that means real estate cost those firms about $7.5-billion. That’s A Big Number, but to get an instinctive notion of how big exactly, consider that domestic US Hollywood box office revenue has averaged about $10—11 billion annually over the last couple of decades. Our real estate spend isn’t far behind that (and that’s just the AmLaw 200, not the industry).

How much of this might we save in a post-Covid world?

It’s very early to see much real data on this, but one point is hammered home in the Cushman & Wakefield report repeatedly, and we here are hearing similar stories: If you’re going to need less space, it might as well be nice.

In other words, you might move from Class B+ or A- space to AAA and hold your spend level constant or even see it go down. The moon shot Hudson Yards development on the far West Side of Manhattan is mentioned by name more than once as an example of “super amenitized” space (I did not make that coinage up, folks, but I’d apologize to you if I had), and firms like Latham, Milbank, and Skadden have already planted their flags there.

[It may seem odd or even perverse to read that goods and services that cost more can be desirable by virtue of that, but the phenomenon is fairly widespread in real life and even has a name: “Veblen goods,” namely items that are more desirable because and not in spite of their cost.]The second point is simply the first real piece of data we’ve seen. UK firms, as most Adam Smith, Esq. readers know, are required to file annual financial statements with Companies House and Allen & Overy just did so. Key data point for purposes of today? The firm’s total (capitalized) lease liability at the end of April 2020 was stated as £559.3m but A&O give it a haircut of £155.3 in their current filing—or about 28%. The New York Times recently noted in an extensive front-page story (“Remote Work is Here to Stay; Manhattan May Never be the Same”) that Lowenstein Sandler may not renew the lease for its 140-lawyer office at Sixth Avenue and 50th Street.

So this brings us to your homework assignment.

If you’re not going to spend as much $$ on real estate, what are you going to do with the savings? Remember that $$ out the door to supporting real estate is never seen again and is pure “consumption” (spent this period for services delivered this period, with no market or tail or terminal value). You could, and I suppose some of you will, simply distribute a large share of it to partners at year-end.

But I have a different idea: What if you could repurpose a lot of that money to investment instead? What investments would you make? Would you even create a “retained earnings” entry on your balance sheet and begin saving for that rainy day or that opportune stroke of lightning that must be seized or lost forever?

In the context of what we’ve learned during Coronatide and what we know will be true going forward, I think there’s one compelling priority, whether it’s all of the saving or a portion. Whatever you foresee, if you think spending the same or less on this is smat management going forward, we should talk.

And the category of spending I have in mind? Technology.

We live and die by knowledge, intellectual and social capital, responsiveness and speed, ability to scale up resources at a moment’s notice, and densely connected human networks. Here’s a pithy, realistic prediction from Daniel Pinto, JPMorgan’s co-president and chief operating officer (interviewed on CNBC last month):

“Going back to the office with 100 percent of the people 100 percent of the time, I think there is zero chance of that. As for everyone working from home all the time, there is also zero chance of that.’’

Bottom line: You do not need nearly as much real estate as you thought a year ago. You need far more technology than you thought a year ago.

Let the games begin.

For information: US rate of R&D investment:

https://www.aaas.org/news/new-data-says-us-rd-has-topped-3-gdp-first-time-ever?et_rid=35078877&et_cid=3718380

Short version: > 3% of GDP. Obviously, comparability of Law to other ventures that have R&D needs thought (ASE has been raising this for years), but in keeping with the current post, thinking about how to use available funds toward a stronger future is as worthwhile for professional services as for anyone else.

Nice dataset, Mark: Thanks! Prompts a few thoughts:

Thanks as always!