The problem is that firms haven’t wanted to admit that partnership principles have their limit. It’s doubtless true that the degrees of freedom of partners in BigLaw are not as unconstrained as they were decades ago—may we add, in many ways for the better? Think #MeToo, the louder drumbeat of diversity/inclusion pressure matched by glacial but previously nonexistent action, pressures around representation of toxic clients, heightened transparency across the board, and more.

“Partnership principles” entail bilateral obligations, duties, responsibilities. At bottom it’s a social and not a juridical compact. Law firms are free to subscribe to the fiction that partners remain unfettered self-guided missiles, but one can hope that was never entirely true and it’s less and less so, for admirable and worthy reasons. Subscribing to a pretense that everyone knows is a pretense can be highly functional, but that’s not what firms say and so it’s not how partners behave.

Partners expect to be treated as such, in full; to them the title is not in the least vestigial or symbolic. They want to voice their (emphatic) opinions, exercise their presumed entitlement to an exhaustive hearing, have an extended conversation about it all, and at the end insist on asserting their prerogatives as an “owner”—which, according to any normal partnership agreement, they are. In a way, can you blame them?

Here we run into what I’ve characterized as the difference between “facts” and “truth.” (Just to clarify, folks, I created this coinage while Obama was President.) The Partnership 101 fact is that equity members are owners, but the truth of today’s nation- or globe-spanning firms is that partners’ rights are fenced in by the realities of scale. What does this mean?

You can petition management for changes, and vote on certain substantive questions, but if the firm chooses a course of action that poses irreconcilable differences with your preferences, your right to object or dissent (“Voice”) has been exhausted to no avail. The only permissible choices remaining for you are to leave (“Exit”) or stay faithfully on board in light of the overall package (“Loyalty”).

But the great majority of BigLaw partners would—we’re talking messy reality, not Platonic organizational ideal—stoutly resist stopping with Albert Hirschman’s famous Exit/Voice/Loyalty triad. That may be fine for the corporate world, where the CEO can pull rank on the EVPs, they on the SVPs, and so on down the line. “But not me as a partner in a BigLaw firm.” There has to be another way, a way to get one more bite at the apple.

Lest you think I lay the blame entirely at the feet of the partners for misapprehending what their title really means, firms are equally culpable: 99 out of 100 boast of how their “collaborative,” “collegial” “culture” sets them apart. If that’s not exalting the values of a powerful, almost romanticized view of partnership, what is?

Now I think we’re getting somewhere: The idealized notion of a high-functioning partnership aspires to the condition of “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers” (Henry V, Act IV Scene iii(3) 18–67). It is, admit it, a romantic vision.

What’s omitted, alas, is the critical ingredient of symmetry, mutual obligation, reciprocity, and stewardship: Uncompromised and bilateral commitment, in other words. (That “merry band” in Henry V was going into battle, after all, many never to come back; we’re asking a bit less here, but that hardly deprives the metaphor of power.) At root, we’re talking about the tension between “WIIFM?” [what’s in it for me] vs. the bilateral social compact.

The concept was memorialized nearly 60 years ago in Judge Simon Rifkind’s “Statement of Firm Principles” for Paul Weiss:

Our objectives are, by pooling our energies, talents and resources, to achieve the highest order of excellence in the practice of the art, the science and the profession of the law; through such practice to earn a living and to derive the stimulation and pleasure of worthwhile adventure; and in all things to govern ourselves as members of a free democratic society with responsibilities both to our profession and our country.

Now ask yourself this—and answer, Scout’s Honor, in the context of your own firm: Is our partnership at all akin to the band of Henry V, a “one-firm firm” even or especially when the going gets tough?

Or in reality does it more closely resemble a “hotel for lawyers,” a place where people can come and go at will with few strings attached, temporarily sharing some overhead, not having to worry about putting together their own financial, billing, or document management systems, and being able to draw from a more or less trained pool of more or less capable associates?

One wise Managing Partner of my acquaintance characterized that bargain thus:

Be careful not to confuse the career aspirations and personal preferences of the current incumbent owners with the mission of the organization. That is not strategy—it is career planning at best, and a bunch of lawyers simply sharing overhead disguised as an enterprise with purpose at worst.”

If your firm is closer to the hotel end of the spectrum than the Henry V end—and my own cheerless conclusion is that 90+% of BigLaw firms are in that wan and pallid neighborhood—then a reasonable person might ask, “Why the fiction of these partnerships? Why not just be forthright about matters and adopt the governance model of a corporation?”

Voicing this recommendation out loud is best avoided. It doesn’t do justice to the reactions I’ve encountered to call them “skeptical:” They go well beyond that familiar territory into some different planetary orbit altogether, somewhere between incredulity and incomprehension. You have offended the demigod of the Partnership Ideal.

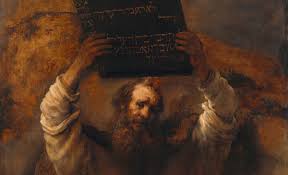

Not for the first time can Scripture give us insight into human behavior.

In Exodus 32, the Israelites, in their Exodus from Egypt, became restless and impatient when Moses left them to ascend the mountain and stayed there too long. They petitioned Aaron to make a golden calf, which he mounted behind an altar, and they offered burnt offerings and brought sacrifices before “sitting down to eat and drink, and rising up to revel.”

When I was younger, this story baffled me every time I heard it: The Israelites had the real thing—they had Yahweh, the Hebrew God of Abraham and Isaac. Why did they need a false idol?

Because the real thing is hard, “a jealous God,” “visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, to the third and fourth generations” (Exodus 20:5) One can understand, if not embrace, the undemanding phony image, inert and content to see the people eating and drinking and reveling. This is a lot easier to take than the firebreather demanding sacrifice.

So yes, real partnership is hard, and therefore rare.

And why does this matter?

Because false, inch-deep partnerships are, finally, not fit for organizational purpose.

If we step back, I believe all can stipulate that a primary goal of a business enterprise is to define, articulate, and pursue a distinctive strategy. So query whether the partnership form or the corporate form is more “fit for purpose”—that is to say, more likely to advance the goals of the firm’s strategy?

The Platonic ideal of partnership is powerful indeed. But in 2021 it’s the rarest of firms that can, or does, live it. The short run seduces almost every time. Wouldn’t we be better off to emerge from Plato’s Cave and take an honest look at the partnership form in the unforgiving bright light of day?

Because until we do, the dynamic of latent centrifugal forces ready to spin up inside a firm like a dormant virus will remain with us, ready to strike at a moment of weakened resistance. All we require is the courage to take a hard look.

I have another take here. I’m not sure if it is correct, so possibly more speculation and musing than any sort of concrete hypothesis. But here goes. Large law firm partners, maybe more than any other professional service save consultants, have seen the ruthless realities of the corporate form up close and personal. I am talking brute form capitalism at its finest that we are all familiar with from the pages of the Journal or FT. Which has just been ratcheting up exponentially since the turn of the century as globalization took off. Slashing 2,000 jobs because you missed earnings last quarter? Yeah, we can help you with that. That merger is going to create worldwide “redundancies” that will have to be phased out? Yep, we’re on it. Not to mention all the trouble that corporations get into that requires a heavy duty litigation clean up squad as a result of chasing every last dollar for shareholders. Lawyers are well familiar with the excesses of the corporate form. Maybe they see that and say, yeah, I’d rather we not have that here. Say what you want about its drawbacks, but partnership in practice is usually a bit gentler organizational form. Underperformers given a bit longer runway to shape up or ship out. Since they are so flat, the top of the organization is that much closer to the bottom. Which allows for more human connection when it comes to things like cost reductions. Are there some costs to it? Yes. Do we make less money? Depends. Is the “safety net” a little larger for all participants? Quite possibly. It’s an alternative to corporate life, which has its own set of drawbacks. I realize I am generalize, but a possible explanation.

Now there are some interesting cross-currents brewing on this front in the corporate world. Stakeholder capitalism is out in general circulation (a debate for a different day). But do partnerships kind of bend in that direction more naturally? Maybe that is what Judge Rifkind was really getting at in his statement of principles?

On a related note, it really does all come back to psychology, doesn’t it? And psychological change at an individual level is probably one of the most difficult things to accomplish in this world. I’m not sure law firms really have the tools to do it.

Partnerships originated 700 years ago as agreements under which the partners, as you point out and Judge Rifkind alluded to, pooled their talents and energy in a common enterprise in the hope of making a profit to share. Not “compensation,” but profit. I’ve sometimes thought that a firm that has a “Compensation Committee” to determine the shares of its owners has missed the point, or is training its owners to think of themselves not as members of a common venture but as compensated (well-compensated, usually) employees who for tax reasons get a K-1 each year instead of a W-2. The result is that those “partners,” as you mention, think of themselves as owners when they want to exercise rights and as employees when they want to avoid responsibilities. They conflate their relationship inter se as owners of a business with their employer-employee relationship with the business itself.

I designed my current micro-firm as a corporation specifically to be able to separate the compensation of employees from the profits of owners. I did that even though for the first several years I was the only shareholder. Could a megafirm do the same? Perhaps, though the firm would have to retrain its current owners in a new model.