What will differentiate winning firms from “mere” survivors is adaptability.

As the Organization for Economic Development wrote in 2019:

Resilience centers on the ability not only to resist and recover from adverse shocks, but also to “bounce back” stronger than before and to learn from the experience.

Adaptability, in short, requires learning from the heart-stopping experience with a gimlet eye trained on where your firm was vulnerable and how to make it “anti-fragile” going forward.

Here’s where we left off, having stolen a page from Law Land’s learning in its emergence from the GFC over a decade ago. I asked if your firm is a Maroon or a Gray and I asked if you think all Grays are the same?

We have extensively fleshed out our model of Law Land being divided into Maroons and Grays (follow those links!) but in 25 words it posits that clients have become more sophisticated, purposeful, and selective in differentiating between matters that represent rare events in the corporate lifecycle, have boardroom visibility and high stakes, and where cost is tertiary, vs. “run the company not bet the company” matters, which need to be dealt with promptly and efficaciously but also at low cost commensurate with their routine nature. The “maroon” law firms win the lion’s share of the first set of matters, “grays” the rest.

Yes; this is a model, not a rigorous map of reality. In the classic phrase of George Box (British statistician, 1919—2013), “all models are wrong but some models are useful.” We are fond of the Maroons/Grays model primarily because we find it useful. As we do here.

If you’re a Maroon, your post-Covid world is likely to look a lot like your pre-Covid world. I set aside details like whether your offices get smaller (this remote working thing has legs), or your practice mix morphs a bit. The foundation of your business model hasn’t changed: Serving the world’s most sophisticated clients in their gnarliest matters through utterly superb, artisanal application of expensively pedigreed high legal IQ.

For the Grays the world promises to be different. Or rather, the same only more so on an accelerated timeline. What precisely are the elements of that “sameness?” By and large, they’re unwelcome:

- As the indispensable Jae Um just pointed out, the conventional wisdom that the AmLaw 200 is “a perpetual growth engine” is false: “The real story here is one of sustained and gradual consolidation rather than perennial prosperity.”

- In 1998, the first year of the “200,” the list collectively embraced 58,000 lawyers or 6% of ABA membership;

- By 2019 the lawyer headcount had more than doubled to 134,000 and 10% of ABA membership.

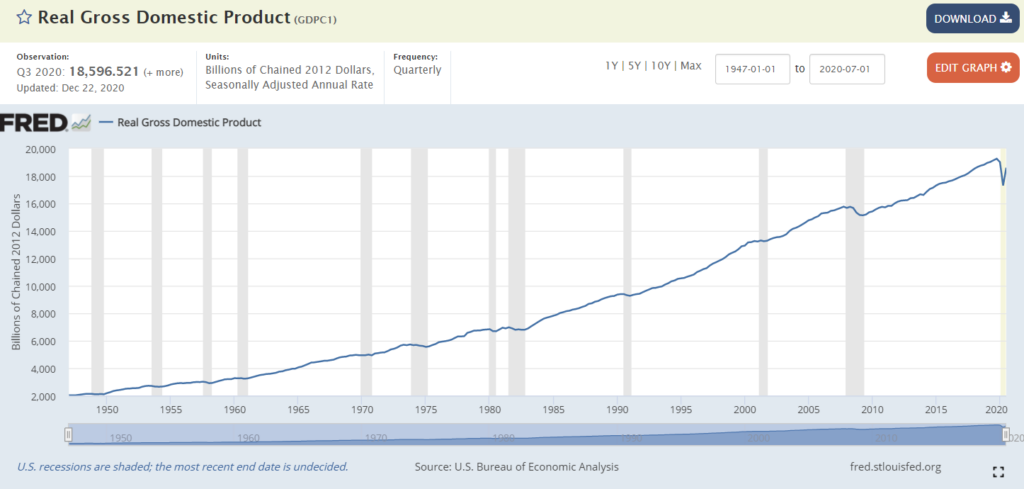

- As we’ve demonstrated ourselves, while nominal revenue of the AmLaw 100 rose 54.4% over the period 2010-2019 (4.9% annualized), once you adjust for inflation (19.5% per the BLS) and headcount growth (24.4% per AmLaw), the net real growth in constant dollars was 3.9% over the entire decade. This during the longest sustained economic expansion in US history, officially running from June 2009 to February 2020, or 128 months.

- Even more tellingly, the average real, inflation-adjusted GDP growth over that 10+ year period was 1.1%/year, while the AmLaw 100’s comparable growth rate was less than 0.4%, or one-third the growth in GDP.

This, to paraphrase the late great Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, is “defining growth down.”

It would be churlish to ask the macroeconomic gods for a more sustained period of “wind at our backs” and this is the best we can do? But we must continue on this jolly track.

Two more points:

First, if you’re a Gray or large components of your revenue stream come from “Gray” activities, you now face nontrivial competition from NewLaw to handle run-the-company or business-as-usual matters. At the very least, you need to have a ready answer if clients ask why large components of and activities comprising those matters shouldn’t be unbundled and handed off to NewLaw or accomplished through a different service model.

This is the first noteworthy place where learning from the GFC breaks down: NewLaw had no measurable market presence a decade+ ago during the GFC; now it’s an established, capable, and sizable part of the legal service delivery supply side.

[There are responses to this, which we’ll get to in Part 3 of this series; but responses there need to be.]Second, and perhaps even worse—we cannot come up with a snappy response for this one, try as we might—is that looking at that deplorable lackluster AmLaw 100 performance more closely reveals that this is a situation where averages mislead to the point of fibbing.

The difference in performance between the top 20 or first quintile of those 100 firms and the rest is striking. Back in August (“Part 3 of Our Series on the AmLaw 200: Envy and its Discontents”) , we published what we reproduce below showing the performance of each of the five quintiles of the AmLaw 100 on three core financial metrics. These charts show the relative performance of each quintile vs. the AmLaw 100 as a whole over the period 2010—2019.