In our “Build Back Better” series discussing how law firms, and the rest of the legal services industry, may [want to] change once humanity emerges from this surreal Coronatide interregnum, we’ve focused on the microeconomics of the industry, if you will: The office of the future, the use of technology in running firms and outreach to clients and others, professional development, training, and acculturation, managing, leading, and so forth.

Time for some thoughts on the macroeconomic front: How is the global economy changing, what trends has the “Covid slingshot” accelerated, and what might you want to think about as you envision re-configuring your firm for the next chapter? If you think envisioning potential future scenarios is a mug’s game, you can (a) stop reading right here; and (b) pause for a moment to reflect on what qualifies you to be a leader.

We’ll take our cue from sources ranging from Alliance Bernstein research and McKinsey to the usual suspects: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Financial Times.

Here are a few of the major themes it’s plausible to see accelerating in future. Following this list, I’ll take a discursive look at potential implications for BigLaw of two—the shift in the globalization tide from rising to receding, and the rapidly declining fortunes of the fossil fuel industries.

- Global debt overhangs, proximately caused by emergency governmental measures to cushion the shocks of the Covid Depression, but fed in the longer run by suppressed economic activity (read: lower tax revenue) and increased transfer/social insurance payments.

- A massive step-change reset in the productive uses of large swaths of commercial and other real estate:

- Demand for office space substantially down, perhaps permanently (on a GDP/capita basis). “WFH” works and both companies and employees have their own reasons to embrace it, on some scale, for good. No, skyscrapers in major metropolitan central business districts are not about to be torn down, but economic pressure may be intense to re-purpose a substantial share of their square footage.

- An irreversible shift from bricks and mortar retail to online.

- And, farther off, it’s conceivable (if alarming) to foresee massive voluntary or forced migration from very large swaths of residential areas made hostile, unlivable, or unaffordable by climate change.

- A “reset” of the globalization imperative of the past few decades. From WWII until a few years ago, globalization (measured by exports as a percentage of GDP, worldwide) grew essentially unabated, from 4% in 1945 to 26% in 2013. It then reversed, for a number of reasons—some reinforced by our global Covid-19 experience, none dampened by it:

- Ocean-spanning “just in time” supply chains turned out to be less reliable than we had all assumed (Covid-boosted);

- Regardless of where parts originate, a production shutdown for just one component (the famous “single point of failure”), if it’s critical and has no substitutes, can bring an entire manufacturing company to a halt (Covid-boosted);

- And the dollar cost savings of segregating design/engineering in (say) the US and manufacturing/assembly in (say) Asia turned out to come at a quality/reliability cost. If the engineers and designers couldn’t see first-hand how the assembly process did (or didn’t) work and talk to the front-line production personnel, defects, rework, and costs ballooned. (GE famously sent all of its “Appliance Park” Kentucky manufacturing to China many years ago, only to bring it back a few years later for this very reason, a decade or more pre-Covid.)

- Populism has zero kind words for globalization; if you can predict when the worldwide populist wave will recede, be my guest.

- Globalization

The implications for BigLaw of the switch in tidal direction for globalization is, one would think, close to self-evident. National and regional firms may find their office footprints back in favor after decades of people singing the praises of globe-spanning multinationals. (The virtues of having offices on a few continents or more may have been less grounded in reality than in pizzazz, but missing that boat still stung and arguably led some firms astray.)

Global law firms will always have their place—this is not a binary conversation—but perhaps (a) not quite as many; and (b) a more selective/targeted footprint for those that remain.

We have long preached the virtues of focusing on a set of practice areas that are complementary to one another, but the advisability of applying that lens to one’s worldwide office footprint has seemed less apparent to many: More/more/more was what “global” was all about. Maybe it’s time to revisit that assumption.

If you perform that latter exercise, a word of advice? Start with a hard-headed, numbers-driven analysis of the global footprint of your key clients. To torture the old Wall Street saw, “Planting flags is vanity, but profit is sanity.”

- The Energy Industry

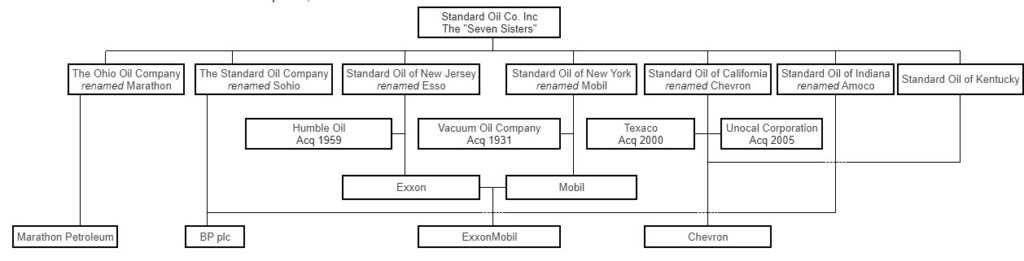

These sibling companies are almost indelibly robed in our memories with Big, Multinational, Important, Central to the Economy.

A bit of perspective.

Forty years ago (January 1981—think Reagan/Thacher, the introduction of the original IBM PC, and the recent death of double-digit inflation at the merciless and brilliant hands of Paul Volcker), the S&P 500 was 29% made up of energy by market cap. In 2008 (the GFC), it was still 17% and oil was at $140/barrel. Today the smallest sector in the S&P @ 2.3% is: Energy.

The decline in energy can be seen by comparing the market cap of the seven largest oil companies to the market caps of Apple, Microsoft, or Amazon. Each of the three technology companies is now valued at more than $1 trillion; Apple is valued at more than $2 trillion. In contrast, the combined value of BP, Chevron, ENI, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Total, the last of the “supermajors” formed at the turn of the century, is less than $700 billion.

—Philip Verleger, “I am a climate optimist,” Niskanen Center/September 2020.

And with Salesforce taking the place in the Dow of–you know what’s coming–Exxon itself just last month (after 92 years of Exxon being a DJIA component), the only traditional energy player left among the 30 stocks is Chevron.

Now, this is not a column about investment strategies, but can The Majors save themselves by pivoting to solar, wind, etc.?

They seem to be trying:

The European supermajors are trying to save themselves by abandoning oil. BP, Shell, and Total have all announced plans to expand their activities in renewable energy while cutting expenditures on oil. BP has gone further than Shell and Total, which both still see a role for natural gas. Investors have not been fooled.

BP is leading the way here. The company has announced a tenfold increase in its investment in low-carbon energy sources, reaching $5 billion per year by 2030, according to Reuters. The company also intends to achieve a twentyfold boost in renewable generating capacity.

–(Ibid.)

The day after this announcement, BP’s stock slid sharply, hitting a 25-year low. Then of course came word last week that California (11% of new car registrations in the US) was announcing a ban on the sale of new gasoline-powered cars and light trucks effective in just 15 years. The market (again) has internalized this knowledge:

Market cap Tesla: $361.7B

Market cap Exxon: $145.1B

Ratio: 2.49:1

What could have seemed a safer bet as a core practice area than oil and gas? Remember firms piling into Texas and Alberta? And it has long been a truism so unremarkable as to make one suspect one who voices it of being a simpleton that economic growth and energy demand are linked.

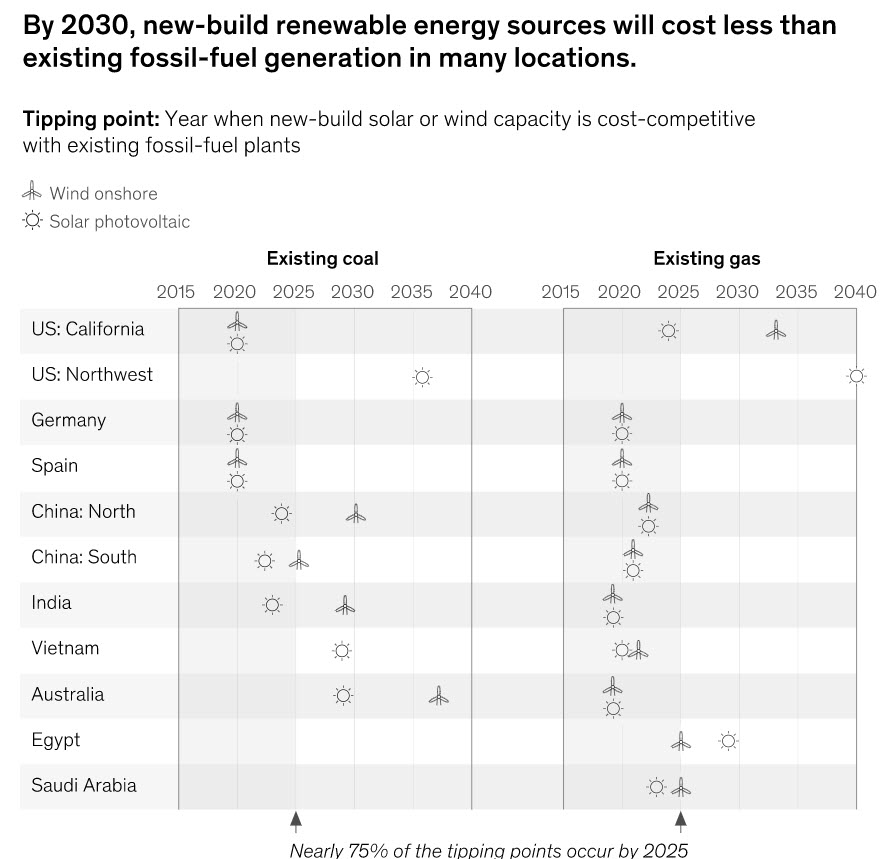

But per McKinsey, “past is not always prologue.” They foresee a decoupling driven by:

- A drastic decline in energy “intensity” of GDP as the global economy moves away from industrial to service functions.

- Growing energy efficiency, thanks to technology and changes in human behavior.

- A growing share of energy in the form of electrification, once a bogeyman but now the darling of efficiency fans.

- And of course the shift from fossil to renewable power.

Enough said.

Astute readers will recognize that this article is less about the dimensions of specific changes that may be afoot on the macro front and more about our theme from Day One of Adam Smith, Esq.: “Think” Or, as the Italians might put it, stai attento!

The world is full of highly qualified experts who get paid to prognosticate for a living, and you know where to find them. Take what you’ve read here as an invitation, or better yet an entreaty, to keep your eyes and ears open and your brain in critical-thinking mode. “Past is not prologue,” indeed.

Bruce: Just over a year ago, ASE ran a fascinating string of posts distinguishing “Maroons” from “Grays” in Lawland. Now we are considering what “Build Back Better” may mean. I wonder if building back better means the same thing to Grays as to Maroons (I doubt it), and whether thinking about where one’s firm lies in that conceptual space might be instructive in today’s circumstances. Perhaps we are entering a time in which the Splendid Grays will look especially strong?