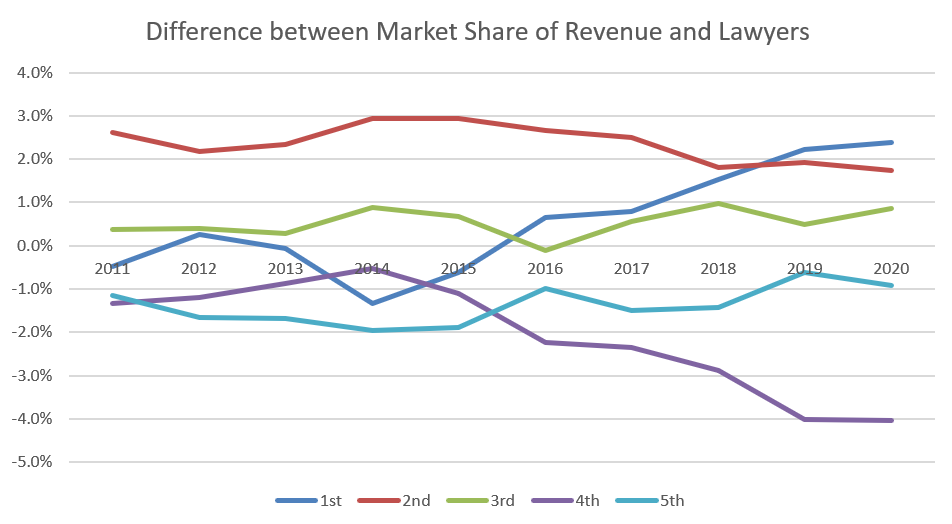

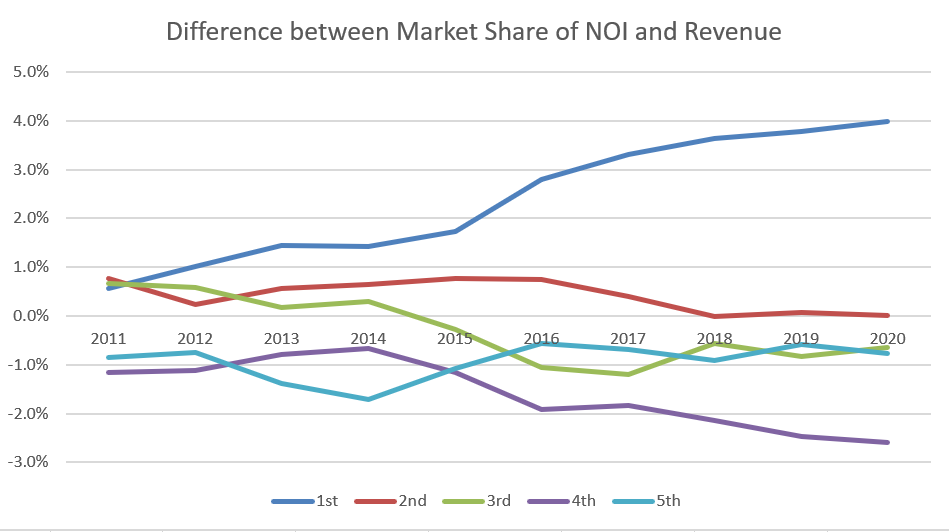

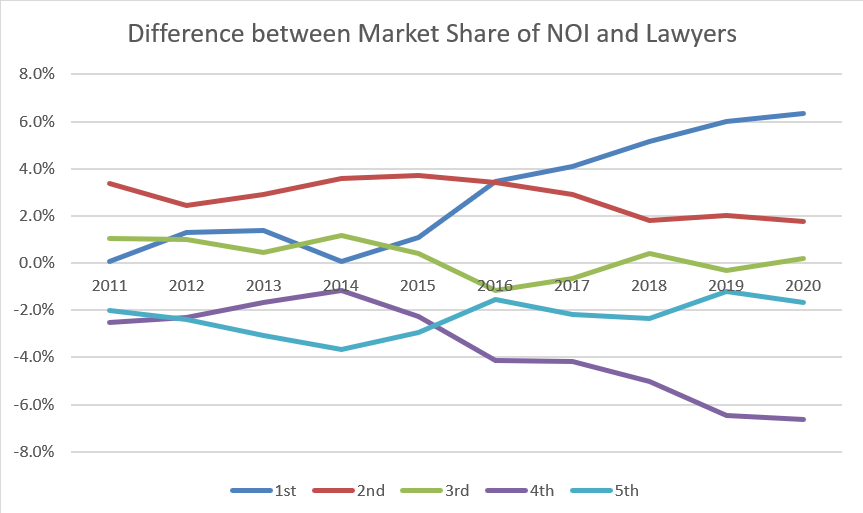

Now that we can visualize the big picture, here’s what we see happening at a macro level:

- The 1st and 2nd quintiles have traded places: At the beginning, the 2nd strongly outperformed the 1st on two of the three metrics and matched it on the third. Today, the 1st appears almost insurmountably in the lead, especially on the two more purely “financial” series pairings: Generating more NOI from revenue and more NOI from a lawyer.

- The 3rd and 5th are leading steady, relatively unexciting lives. They’re not taking gold or silver but they’re very rarely at risk of bringing up the rear.

- The Sad Cousin award goes to the 4th, hands-down.

So what do we make of all this?

First and foremost, no one in the 4th quintile firms is suffering in the least. (Indeed, their relative position may be what whoever coined the term “First World Problem” had in mind.) That one quintile or another would bring up the rear was effectively built into the techniques we used to analyze the data. They were designed to force-rank winners and losers.

Reflect for only a moment: For each of the 10 years in our sample, the AmLaw 100 firms together generated a finite and defined amount of revenue and NOI using a finite and defined number of lawyers. If one cohort is up, another has to be down. This is truly a zero-sum analysis.

And if no one in the 4th quintile is suffering (a self-evident truism if ever there were one—most Americans would trade their current station for a position in any of the “4th” firms in a heartbeat), then, a fortiori, life in the 3rd and 5th quintiles is also splendid.

To us, the fascinating pattern we discovered when we turned over this rock was the 1st and the 2nd swapping places. To generate a hypothesis that might explain that, we took a detailed look at exactly which firms were in those two quintiles (yes, by name) over the years in question. Wisely or rashly, here’s what we think may have been happening.

What if the caliber of lawyers and of firms that make up the 1st and 2nd quintiles has slowly been preferentially migrating, in quality/elite reputation/prestige, to the 1st? In other words, our impressionistic view is that there were some extraordinarily high-caliber firms in both quintiles 10 years ago, but now the 1st is almost embarrassingly top-heavy on high-prestige firms and the 2nd has lost several through up-market (into the 1st) and down-market (out of the 2nd) moves.

Definitively proving or disproving that would require a minute analysis of all, or a very large sample, of lateral partner moves, client defections/acquisitions, positive/negative media mentions, and perhaps more, across all those firms for a decade. If some intrepid forensic data analyst out there was casting about for their next project, be our guest.

In the meantime, consider this possible theoretical explanation: If labor markets are efficient—and there’s no reason to think the market for talented lawyers suffers systemic informational asymmetries or other modalities of market failure—then the past decade has seen the rational, efficient, “sorting” of Big Law Firm partner talent from platforms that may be suboptimal towards platforms that are a better fit.

Understand this should, and if our theory has legs, surely has, worked both ways. A Big Law partner can find themselves at the “wrong” firm because their skill sets and ambitions cannot find adequate expression and running room where they are or, conversely, because they’re in highly rarefied air—too rarefied for their comfort.

Regular readers of Adam Smith, Esq. know that our view on the ever-upward spiral of lateral partner moves in our industry is, shall we say, unconvinced, but what we may be seeing here in the “swap” between 1st and 2nd quintiles since 2011 implies it’s not all churn. There might be an efficient labor market out there after all.

We cannot resist offering a thought in closing by way of, “What on earth do you think I should actually do with this?” We hope our answer will offer a solution, and an escape route, if at this point you’re feeling envious. Envy is no place to live.

The literature on leadership speaks with one voice on little, but that a prerequisite for strong leadership is “knowing yourself” would receive near-universal agreement. So: Know your firm.

The vast majority of readers will not happen to be in the 4th, or the 1st, quintiles. But it doesn’t really matter “where” your firm is: Remember even the 1st and 4th quintile patterns we’ve been discussing are the averages for those quintiles. Individual firms differ.

So forget where you “are,” and calculate how your own firm’s gross revenue, NOI, and lawyer headcount stack up against some plausible, publicly available benchmark data.

If you discover your firm “looks like” a 1st or “looks like” a 4th quintile firm, you have learned quite a bit already. Think of these patterns as packed full of information.

Which pattern you more closely line up with will help determine, among other things, what talent you can recruit and what “degree of difficulty” in terms of client matters you can aspire to compete for. If you like where you are, reinforce the strategic, cultural, and economic conditions and aspirations that got you there. That’s “easy”—as if anything in leading a law firm were easy.

If you don’t like the pattern your performance resembles, you have one simple and one complex task ahead of you. Simple: Figure out what strategic and tactical adjustments would help your firm pass through the exit door. Complex: Persuading your partners to do it, and engineering the cultural shifts that might be required to make it stick.

Now, aren’t you glad you asked what to do with this?

[1] Methodological note: The data we focused on calculated each quintile’s performance relative to “parity” with the AmLaw 100 average across each of the pairs of data series.

In other words, matching the AmLaw 100 average produced a score +/- 0.00%. A quintile that “outperformed” the AmLaw 100 across the two data series under analysis would generate a positive number and an underperforming quintile a negative number.

We deemed: (a) more revenue from fewer lawyers; (b) more net operating income from fewer lawyers; and (c) more net operating income from less revenue; all to be good things and therefore scored them as positive variances. The opposite outcomes produced negative scores.