At the end of installment #1, we promised you we’d discuss what happens if you apply Porter’s famous “five forces” to the Maroons and the Grays. Shall we?

Insight from Porter’s “Five Forces”

In 1979, Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter published his classic article “How competitive forces shape strategy,” introducing his “five forces” model. Here it is, schematically:

This is designed to help firms assess the critical dynamics of the marketplace they operate within. Unpacking it a bit, we have:

- At the center, competitive rivalry: This is the bread and butter of industry competition. Bud competes with Miller, Ford with Chevy, Coke with Pepsi, and so on. It may not be easy—it may be all but impossible, in some cases—but at least it’s more or less a known, understood quantity. Some of your firm’s rivals will be fierce and others gnats not even worth swatting away, but it’s a familiar playing field insofar as it goes.

- At noon, the threat of new entrants. Before Tesla, any global car manufacturer would have told you the threat of new entrants was somewhere between nonexistent and imaginary. Maybe not so fast. (It’s still pretty daunting to launch a globally integrated petroleum company, but then again, maybe the world has all it needs right about now.)

At the other extreme, new airlines seem to arise almost every day: Lease a bunch of planes parked in the Arizona desert, hire some furloughed flight crews, build a website, and you’re off and running. Come to think of it, the barriers to starting a new law firm are even lower; most of us could fund the startup costs with our Amex card. - 3:00 o’clock: The bargaining power of your clients. How price-sensitive are they? (Or, what is their price-elasticity of demand?) Are they prepared to accept your “off the shelf” goods and services or do they expect customization? High-touch or self-serve? You get the idea.

- 6:00 o’clock: The threat of substitutes. Is there a substitute for car ownership? Increasingly, millennials seem to be saying there is, and if “transportation on demand” is actually the definition of the market, they might be on to something: A combination of Uber/Lyft, Zipcar, mass transit, and a preference for urban over suburban living could do it. On the other hand, there’s no tenable substitute for long-haul airline service.

- 9:00 o’clock: The bargaining power of your sources of supply. For law firms, the only supply chain component of any consequence—the only one that matters– is talent in the form of lawyers and business professionals. (Office space, email, and word processing are all available en masse as, essentially, commodities with by hypothesis no bargaining power.)

This is how Porter described the intersection of the five forces and corporate strategy:

Whatever the collective strength [of the five forces], the corporate strategist’s goal is to find a position in the industry where his or her company can best defend itself against these forces or can influence them in its favor. The collective strength of the forces may be painfully apparent to all the antagonists; but to cope with them, the strategist must delve below the surface and analyze the sources of each. For example, what makes the industry vulnerable to entry, What determines the bargaining power of suppliers?

Knowledge of these underlying sources of competitive pressure provides the groundwork for a strategic agenda of action. They highlight the critical strengths and weaknesses of the company, animate the positioning of the company in its industry, clarify the areas where strategic changes may yield the greatest payoff, and highlight the places where industry trends promise to hold the greatest significance as either opportunities or threats. Understanding these sources also proves to be of help in considering areas for diversification.

So there’s your challenge.

Now, applying Porter’s model to the Maroons, what does it look like?

We submit it looks like this:

In other words, for the Maroons the only critical external force they need to worry about is the bargaining power of lawyers. (One of our more droll friends calls this the Kirkland & Ellis effect.) Desirable laterals—and your top-drawer home-grown incumbents—know their value on the market and by and large any social or reputational restraints on seeking to capitalize on it have fallen by the wayside. That’s why we noted that a strong and defensible PPP is a KPI for the Maroons.

On the other hand, what do they not have to worry about? There won’t be any new entrants, at least not without a decade or more’s warning; price is not a selection criteria for Maroons’ clients so take that effectively off the table; and there is no substitute for what they can do.

Of course—and this always should be a bedrock assumption—they do have to worry intensely about their competition, the other Maroons. But presumably they’ve been doing that for a long time.

Now, shall we apply Porter’s model to the Grays?

The exact inverse result.

I have doubled down on emphasizing “rivalry among existing competitors” because the competitive set for the Grays includes not just other Grays but their own in-house corporate clients’ legal capabilities, and NewLaw—and combinations of all of those. So the “rivals” of Grays is a much more complicated, shifting, landscape than it is for the Maroons, who only have the other Maroons, a limited and highly proscribed category, to worry about.

Threat of new entrants? You bet. The CAGR of NewLaw revenue over the past two to four years (Thomson Reuters and Adam Smith, Esq. estimates) is 20—40%. Even at 20%, NewLaw revenue would double in four years. (If you think a healthy growth rate for law firm revenue lately is 5%, that would grow just over 20% in four years.) Nor should you comfort yourself, if comfort it would be, with the easy assumption that $1.00 to NewLaw represents one and only $1.00 away from law firms. Actually, based on substantial data, the real multiplier is on the order of 3—4X. For every $1.00 of revenue NewLaw gains, law firms lose $3-$4.[1]

Bargaining power of buyers: This is what the incessant mantra of clients’ demanding “more for less” is all about; remember that a defining selection criteria for clients among Grays is price. Once capability is stipulated—and it is or you wouldn’t even be on the client’s short-list—price can be decisive, or at least highly influential. If we have heard the lament from law firm partners, “We can’t get the rates we need,” once we have heard it hundreds of times. Of course this complaint brutally exposes how many lawyers misapprehend the most fundamental reality of how markets work. Clients do not pay their service providers what the providers “need;” they pay what the market says is the going rate for that service.[2]

Threat of substitutes? Also very real. But it’s not only (a) other grays; (b) in-house capabilities; and (c) NewLaw, it’s also one other substantial if impossible to quantify threat: Doing without. That is to say, from the perspective of the corporate buyer, many times the opportunity to address a problem by applying legal services to it is no more than that: An opportunity and not a requirement. There may be other simpler or more direct solutions, including just plain doing nothing.

Our experience tells us that many law firms underestimate how much of legal spending is actually discretionary in the eyes of their clients; or, even if a matter must be addressed, it can be done economically with minimal fuss (a stern letter in lieu of a court filing, e.g.).

So all in all, Porter’s five forces expose how dramatically different are the business landscapes facing Grays from that facing the Maroons.

Implications

If you’re a Maroon

Basically, you know how to do this. Running a Maroon is running a law firm a lá the classic Cravath Model, which we’ve been working under for over a century. Always keep top of mind that your first priority is performing your core competency of recruiting, retaining, and training lawyers practicing at the highest levels—who have solid business acumen as well. Superb legal talent is your scarcest resource and the one most susceptible to being competed away by your most effective competitors.

This means a high, strong, and defensible level of PPP is actually a KPI for Maroons, whereas it’s nothing of the sort for Grays. We can spot Grays their desire to have bragging rights about PPP, but frankly that’s all it is, whereas for Maroons a subpar—worse, declining—PPP can represent an existential threat in the shockingly near term.

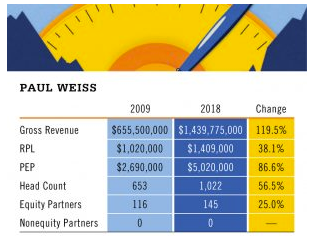

Another way of articulating the challenge for a Maroon firm is: Don’t screw it up. Maintain your relentless focus on what you’ve always done best. Accept no “B” players either among your partners nor, frankly, among client matters you regularly accept. (We’ll talk a bit at the end about whether any given firm can be both a Maroon and a Gray, so hold your fire on this for a minute.) Brad Karp, Chair of Paul Weiss, nicely summarized the “focus” mantra in a recent interview with The American Lawyer:[3]

“Our goal was to develop market-leading practices in litigation, white-collar defense, public M&A, private equity and restructuring. To achieve this, we needed to make some bold strategic investments and wisely deploy some of the capital we had created,” Karp says. …

“One of my first actions as chair, back in 2008 and 2009, was to shift resources away from certain niche practices and geographic regions that were peripheral to our strategy and to focus our energies on mission-critical, client-centric practices for a firm centered in New York and Washington,” he says.

He also succinctly identifies the firm’s positioning in the bullseye of the Maroon target: ““Our goal is to be the go-to firm, the safe choice, for the most important companies in the world, on their most important matters, where the stakes are highest.”

Does this mean Maroons can ignore all of the operational discipline and process-optimization hygiene that have to be the Grays’ calling card? No, it just means that rather than those capabilities being the primary feature of the firm—what it’s “about,” if you will—those capabilities need to be excellent as part of the comprehensive package of service delivered to the client, which also includes world-class legal expertise. Think of it this way: Toyota needs to be very good indeed at “kaizen,” or else they risk forfeiting what makes Toyota distinctive. But Mercedes and BMW better have fit and finish and quality control on a par with their prestige (and pricing) as well. That’s just not the primary thing you’re buying when you go for a Mercedes or a BMW.

And the implications if you’re a Gray

In 25 words or less, a more business-like approach must infuse all aspects of the firm’s services and delivery.

Amusingly or alarmingly, depending on your point of view, when we recommend to law firms that they operate in a more “business-like” fashion, the single most common reaction we get is, “What does that mean?”

If that’s what you’re thinking, read on.

The primary dimension to running your firm like a business is simply having a strategy. Michael Porter observed that “strategy is a choice;” our preferred way of saying the same thing is, “strategy means saying no.” Once you’ve established that, here are other critical components of approaching your clients and your engagements in a businesslike fashion:

- Make sure high-level, very well-qualified (and appropriately compensated) business professionals have not just a seat but a voice at the table.

- Operate through intellectually and cognitively diverse client-facing teams: Lawyers, sure, but also professionals from operations, finance, data analytics and IT, competitive intelligence, journalists/story-tellers, and more.

- Replace or upgrade your financial systems so they can provide you with near-real-time revenue and profitability statistics, resource allocation, alerts and “escalators,” and make sure that your metrics have consequences (positive and negative) for those responsible for managing them.

- Put in place a thoughtful, comprehensive strategic client account management program. Stick to it.

- Invest in obtaining serious, reliable business intelligence, and use it as your basis for decision-making. No more decision-making by anecdote or pursuant to what the loudest voice in the room said last.

- Did we mention holding people accountable? For goals, deadlines, performance hurdles?

- And finally, spending a small but non-trivial amount of your annual revenue on R&D; your clients all do.

In a Gray, lawyers are a part of the team, but only a part; they are not first among equals. This means they are not permitted to second-guess or micromanage business professionals—no more than the business people would presume or care to oversee the lawyers’ trial or deal negotiating strategy. Let each group do what it does best and stay out of the other’s way.

If you’ve followed what we advise here about being a Gray, one over-riding thought might be in your mind: This doesn’t sound much like running a law firm in days of old. No, and that is very much the point: One we will return to at the conclusion.

[1] The dataset we saw, as of May 2019, can be summarized as follows:

| Matter type | Law firm: cost and duration | NewLaw: cost and duration | ||

| Small litigation (M&A reps & warranties insurance claim) | $111K | 8 weeks | $29K (-74%) | 3 weeks (-63%) |

| Mid-size international arbitration (3 continents, 2 law firms) | $2.0M | 23 weeks | $0.3M (-83%) | 6 weeks (-73%) |

| Large regulatory investigation (SEC, NYAG, CFTC) | $18M | 80 weeks | $4M (-78%) | 30 weeks (-63%) |

| Client comments re quality: | “[NewLaw]’s work product is more substantive [than] the law firm’s.” “Exquisitely helpful…such a good job [that] we now have time to think up new thoughts.” “99.97% accurate; they serve as co-counsel, not just a vendor.” | |||

[2] We don’t want to pick on partners. Associates exhibit belief in the same delusion when they rationalize their entitlement to high starting salaries by reference to what they “need” to be paid to handle the high student loan burden they have incurred.

[3] “Crash Course: How a small group of firms pivoted and profited after the recession,” April 23, 2019, available at https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/2019/04/23/crash-course-how-a-small-group-of-firms-pivoted-and-profited-after-the-recession/

Intuitively, the 3 or 4 multiple feels about right to me (“half the rates * half the time”) but this field is so full of people with axes to grind that it would be interesting to know more about the dataset cited – how many matters were in the three categories, how the researcher ensured comparison of like with like, how many clients were interviewed, how an unbiased sample of clients was identified, etc. Are you able to add anything on these topics?

Actually, Graeme, the data we display in the fn. IS all the data; it was three separate engagements which we summarized descriptively. But this particular NewLaw corp. has been in business for well over a decade and their experience over that entire span of time has been comparable. 2X would be very low and 5X would be very high but 3-4X covers the bulge in the bell curve.

Your model makes sense to me. What impact does lawyer megalomania, er, self-delusion have on understanding where they fit on the spectrum? If maroons and grays should proceed on radically different paths to succeed, a key component seems to be the ability of firm management to identify which camp they’re in so they can take the right actions. Do you think lawyers have the self-awareness to do that?

Consider, e.g., a firm in the Vault 50-100 range. They’re likely a mid-tier NYC firm or mediocre but large national firm. They almost certainly fall into your gray category. If you talk to them, would they perceive themselves as grays? Or would they say (as I’ve heard repeatedly), “We’re a bet-the-company firm when it comes to [super narrow niche] in [super narrow market] in [super specific industry].” The lawyerly ability to distinguish a fact set plus a healthy amount of hubris likely–in my mind–ends up with many, many more firms identifying themselves as maroons than is likely to be the case. What impact does that have? The firms that have a proper view of their place in the pecking order, that know they’re grays and are okay with it, have a competitive advantage going forward?

We’re going to get to that!

One of the most popular lawyerly parries is “Yes, but that doesn’t apply to [me/my practice/my office/my clients/my firm].” This immediately after they’ve asked you “but what are all the other firms doing?” Sometimes I’m tempted to respond, “You don’t really want to know because if you don’t like what I tell you you’ll dismiss it.” But I have restrained myself and will endeavor to continue to do so.

Bruce –

Many law firms operate under old overhead models that are not based on modern cost accounting principles. Sometimes it’s even driven by a desire to hide how much overhead a practice really takes to run, and that it’s entirely unprofitable. Is there anything to do about it other than run away?