Ask almost any Managing Partner or office leader this question and odds are about 98% that the answer you’ll get is, “It depends.”

Indeed.

We wish there were reliable, consistent, industry-wide data on laterals’ success ratios, but we’ve never seen it or even heard rumors, like those of the Sasquatch, that such data exists. Partly it depends on what “success” or “value” means: Does it mean:

- Delivering as much or more than the book of business they promised? If so, >90% are probably failures.

- Covering their costs the very first year? After the second year? The third?

- Simply surviving–staying onboard–for three years? Five? Longer?

- Building a thriving practice in precisely the area the firm hired them for–to fill a capability gap? Very rare, but a beautiful thing to behold when it happens.

Whatever the actual experience of firms has been, without question there are smarter and dumber ways to go about the lateral hiring, or M&A, process. Thanks to PwC’s strategy + business (“Seven steps for highly effective deal-making“), we have some pointers that mesh nicely with our on-the-ground experience. (The study data came from a survey of over 600 senior corporate executives around the world who had made at least one significant acquisition and one significant divestiture in the previous 36 months.)

It starts, appropriately enough in this area, with a dose of cold water in your face. While 61% of corporate executives in their study believed their last acquisition created value, 53% of the acquirers underperformed their industry peers in the two years following the deal.

So where did these (big) dealmakers go wrong? You might think from the title of the piece that there were seven areas of miscues, but the authors condense them to three:

- Losing sight of the strategic rationale;

- Fuzziness about how exactly value will be created; and

- Shortchanging the need to work on cultural integration.

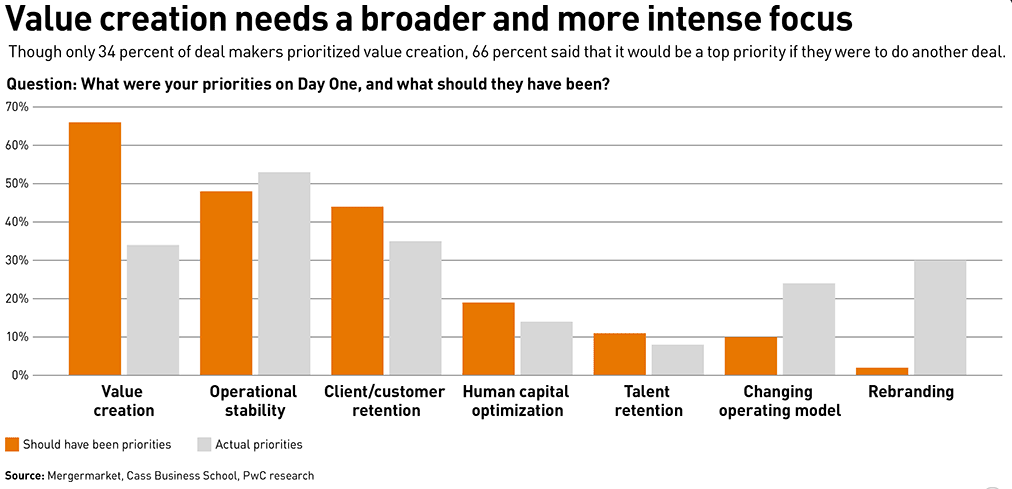

Here’s a snapshot of what the dealmakers actually focused on when the acquisition was consummated vs. what in hindsight they should have prioritized:

A couple of highlights, for me:

- Two-thirds said “value creation” should have been first and foremost, but only one-third thought so at the time

- Interestingly, “operational stability” is not as highly ranked in hindsight as it was when the deals were done; and

- You’re wasting your time on “rebranding!”

All very interesting, but let’s step back and ask the more existential question: Should you be doing this deal in the first place? Here the introduction from our faithful authors cannot be topped (emphasis original):

1. Prioritize the strategic over the opportunistic. In acquisitions, deals driven by the strategic priorities of the acquirer’s business following, say, a review of its existing asset portfolio are more likely to succeed than opportunistic transactions arising from the sudden availability of a target. Eighty-six percent of deals that created value in our research were strategic, compared with just 14 percent that were opportunistic.

Strategic intent should be clear from the outset. Establishing the key objective of your M&A strategy is vital. Is it future-proofing your business by bringing in new capabilities? Enabling your business to access fresh revenue streams? Or even overhauling your entire business model?

“Deals that deliver value don’t happen by accident,” says Bob Saada, deals leader, PwC US. “Transactions should be an extension of your corporate strategy instead of a sudden opportunity. Companies that invest time in strategy, follow that course, and avoid chasing a shiny object just because it’s available will have a much better path to success.”

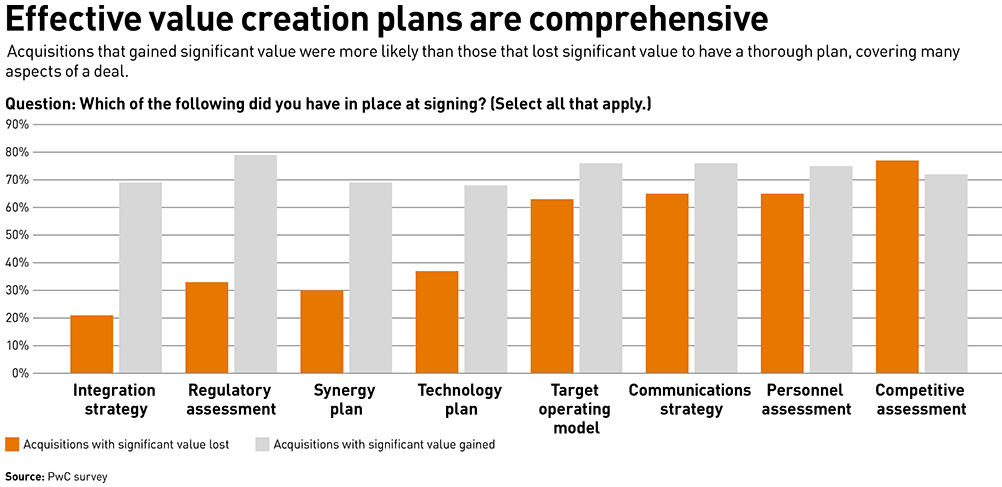

Not only do you need to base the potential acquisition/lateral hire on a sound strategic rationale, you need to plan in advance how you’re going to integrate them into your firm. 70% of acquisitions that delivered increased value had such plans, 80% of acquisitions that destroyed value lacked them.

The other plans (for “synergy” and for technology) that show wide divergence between value-creating and value-destroying outcomes are also, at root, different ways of saying “integration.” (A semantic note: Because the dataset included divestitures as well as acquisitions, factors applying to those were included, and the primary one you see here is “regulatory assessment,” 89% of sellers regret that they did not do more to enhance the value of the spun-off business by optimizing tax and legal structures in advance of the transaction closing.)

Finally, back to integration: It begins at the very start of your talks with the potential target firm or lateral hires. And you will need to spend real money on it. According to the study, over 90% of the acquisitions that added value spent 6% or more of the deal value on integration, while 93% of the value-destroying deals spent less. (I know it may be hard to draw a comparison to “6% of what, exactly?” but notionally think of it as real money. A $100-million acquisition, which probably happens across the national economy several times a week, would imply >$6-million spent on integration.)

Finally, do not leave integration until the deal has closed and the new folks have shown up; that’s way too late.

Marissa Thomas, deals leader, PwC UK, says: “One of the misconceptions in the market is that deal fundamentals such as integration are post-deal issues. They absolutely are not. Successful acquirers and investors work on integration and other core value creation levers at the same time as they conduct their diligence.”

So the next time you meet some lawyers at a conference or a party and you “like the cut of their jib” (yes, a verbatim rationale offered up to us to justify a big lateral hire that didn’t seem to make sense to us), put down your glass, count to ten, and go back to your strategic plan. Your incumbent partners will, or should anyway, thank you.

You quoted this wonderful sentence from the report: “Eighty-six percent of deals that created value in our research were strategic, compared with just 14 percent that were opportunistic.” Within the lure of the opportunistic acquisition (the “shiny object” that’s unexpectedly available) lies another trap for the acquiring firm: that the person or small group pushing for the opportunistic acquisition that doesn’t fit the firm’s carefully-thought-out strategic plan will persuade their partners to revise the strategic plan ad hoc to make the acquisition fit into it. They revise the plan to suit what they’re doing, instead of revising what they’re doing to suit their plan. They end up with an unsuccessful acquisition and a degraded plan.

Thanks for extending this thought in such an astute fashion.

This somehow strikes me as analogous to the reality (which proceeds through training and inculcation to practice and habit to the climax phase of becoming “the air your breathe” and therefore invisible and deniable) that lawyers turn the Scientific Method on its head. Rather than start with data (facts, activities, behaviors) and try to determine, say, causes of action or defenses (litigation) or deal structures and pricing (corporate), they start instead with the desired legal result and maneuver backwards through “facts” and documents to wrestle reality into delivering the pre-determined result they prefer.