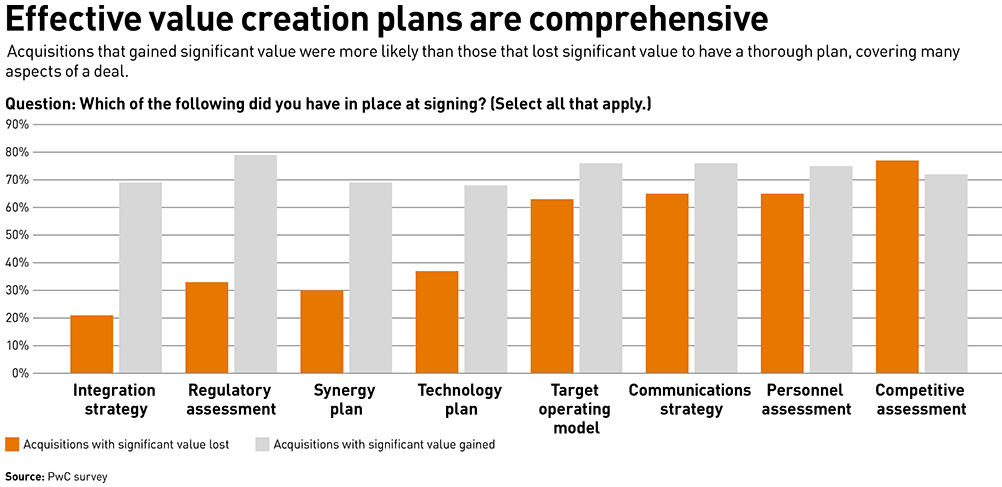

The other plans (for “synergy” and for technology) that show wide divergence between value-creating and value-destroying outcomes are also, at root, different ways of saying “integration.” (A semantic note: Because the dataset included divestitures as well as acquisitions, factors applying to those were included, and the primary one you see here is “regulatory assessment,” 89% of sellers regret that they did not do more to enhance the value of the spun-off business by optimizing tax and legal structures in advance of the transaction closing.)

Finally, back to integration: It begins at the very start of your talks with the potential target firm or lateral hires. And you will need to spend real money on it. According to the study, over 90% of the acquisitions that added value spent 6% or more of the deal value on integration, while 93% of the value-destroying deals spent less. (I know it may be hard to draw a comparison to “6% of what, exactly?” but notionally think of it as real money. A $100-million acquisition, which probably happens across the national economy several times a week, would imply >$6-million spent on integration.)

Finally, do not leave integration until the deal has closed and the new folks have shown up; that’s way too late.

Marissa Thomas, deals leader, PwC UK, says: “One of the misconceptions in the market is that deal fundamentals such as integration are post-deal issues. They absolutely are not. Successful acquirers and investors work on integration and other core value creation levers at the same time as they conduct their diligence.”

So the next time you meet some lawyers at a conference or a party and you “like the cut of their jib” (yes, a verbatim rationale offered up to us to justify a big lateral hire that didn’t seem to make sense to us), put down your glass, count to ten, and go back to your strategic plan. Your incumbent partners will, or should anyway, thank you.

You quoted this wonderful sentence from the report: “Eighty-six percent of deals that created value in our research were strategic, compared with just 14 percent that were opportunistic.” Within the lure of the opportunistic acquisition (the “shiny object” that’s unexpectedly available) lies another trap for the acquiring firm: that the person or small group pushing for the opportunistic acquisition that doesn’t fit the firm’s carefully-thought-out strategic plan will persuade their partners to revise the strategic plan ad hoc to make the acquisition fit into it. They revise the plan to suit what they’re doing, instead of revising what they’re doing to suit their plan. They end up with an unsuccessful acquisition and a degraded plan.

Thanks for extending this thought in such an astute fashion.

This somehow strikes me as analogous to the reality (which proceeds through training and inculcation to practice and habit to the climax phase of becoming “the air your breathe” and therefore invisible and deniable) that lawyers turn the Scientific Method on its head. Rather than start with data (facts, activities, behaviors) and try to determine, say, causes of action or defenses (litigation) or deal structures and pricing (corporate), they start instead with the desired legal result and maneuver backwards through “facts” and documents to wrestle reality into delivering the pre-determined result they prefer.