The hard core bulls-eye of our practice is helping firms assess, refine, or discard and re conceive their strategic plans. We approach and proceed through the course of these engagements–as we do in all our work–without preconceived templates, 2 x 2 matrices or idealized models. What’s right for one firm will be wrong for another, what’s aspirational for one will be delusional for other, slimming down to fighting trim will be right for one and building capacity will be right for another, and so forth.

Yet despite the tremendous variety across the content of all the law firm strategic plans we’ve seen or worked on, what’s almost invariably featured front and center in the final document is “Clients.” This is obvious and hard to take exception to, and I’m sure it surprises no one reading this.

But we always worry, as with any element of a strategic plan, how deeply partners have internalized the message as the plan moves from design and formulation to the work of “head and heart,” day to day living-out embodiment of execution.

I said a moment ago that we worry about firms’ perseverance and diligence in executing every material element of a plan, but I wasn’t quite leveling with you. If other priorities are expressed–greater collaboration, disinvestment in particular practice areas, more authority and accountability given to business professionals (for example)–then yes, we hope the firm will be conscientious, thorough, and determined in pursuing them, but the “clients first” bothers us in a way we’ve struggled to articulate for some time. Now we think we have a hypothesis that might clarify this. Here’s Part 1 of the hypothesis:

Many lawyers do not understand that they’re in a client service business.

They may, and usually do, pay it lip service, but in their core they don’t act it out.

Our first intimation of this hypothesis came a few years ago when we were talking to a senior business executive at a global law firm who had joined a month or two earlier from an even larger global organization in a different professional services business. He said, “At [my old firm], if the client’s office flooded, we would be organizing emergency work space, finding disaster recovery services, and doing everything else we could to help them get past the flood. Here, that would be unimaginable; ‘it’s not what lawyers do.'”

Now, if his example (a real life one) strikes you as preposterous, think about it again. Why couldn’t a law firm do things like that for a key client? Isn’t that what “client service” boils down to? What is the client’s pressing business problem and how can you help solve it?

More prosaically, is what your clients really need always the most profound, beautifully crafted, Supreme Court-clerk worthy, analysis of their legal issue? The most brilliantly creative trial strategy, damn the expense? Because if you ask many lawyers what they think excellent client service means, that is essentially what you’ll hear.

Let’s take this a step farther: What if our hypothesis that lawyers do not see themselves in a client service business has some truth to it? What then do they think their relationship to their law firm is? After all, in professional life there is no such thing as having no goal, no desired outcome, no preferred state of affairs. If their relationship to their firm is not first and foremost about “client service,” what is it about? What, in other words, is Part 2 of our hypothesis?

Bluntly, we think many lawyers believe their firm exists to serve up to them interesting legal questions on which they can demonstrate their impressive legal prowess. The overriding purpose of their firm, in other words, is not client service; it’s to present an endlessly fascinating buffet of thorny legal issues for the partners to enjoy chewing on before moving on to something else tasty.

Far-fetched?

We thought it might be as well, but last week we heard a story that prompted us to publish this column. The managing partner of an extremely well-known global firm was discussing client service with a group of partners, pressing the case that it was all about solving the clients’ business problems, when a dissenting voice contradicted him: “No, it’s about delivering the most finely honed legal analysis, and then doing that again for another client, and again.”

There you have it.

Whatever else this fellow thought his firm primarily existed to do, it was evidently not to put its clients real-world, practical business problems (flooded offices) first; it was to serve this fellow’s interest in pursuing his own preferred intellectual activity.

Now, we have no quantitative data to support this, and it would be impossible to gather any, but it seems to have a ring of truth to it, as well as repeated and widespread anecdotal evidence. Even if it’s only sometimes or partially true, might it help explain or at least clarify some things? Such as?

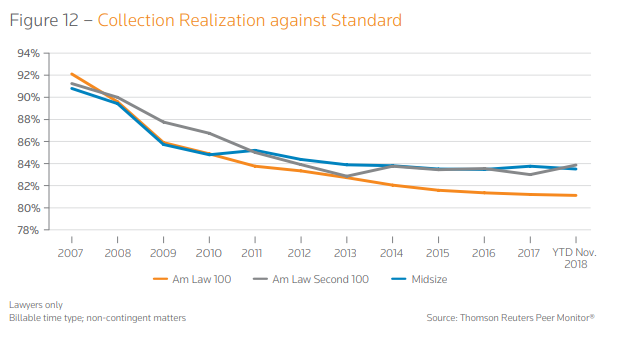

How about chronically low, and still declining, realization? We don’t know about you, but it strikes us that there’s an impressive shortage of self-reflection about this in our industry. It seems to be accepted, like the weather, or rationalized with glib dismissals about what-do-you-expect if you keep raising rates and it all comes out in the wash. By contrast, we think it cries out for a solid, powerful explanatory theory of how this is either a tolerable or a good thing, because if it’s neither we need collectively to do something about it. For the record, here’s the trend from the latest Thomson Reuters State of the Legal Market (2019). Although they break it down by AmLaw First and Second Hundred and “midsize,” the message is essentially the same for all three segments:

Over the past 12 years (since the Great Meltdown), the average among the firms they track (meaning half do worse) shows realization dropping from about 91% of “standard” rates to about 83%, or almost a 10% drop. Looked at slightly differently:

- The discount, willing or otherwise, that firms are giving their clients has doubled from 9% to nearly 18%; and

- Assuming firms have not otherwise enhanced their efficiency or cut costs, the haircut to the firms’ profits has also doubled. (Cost accounting 101: If your fixed costs, mostly people, rent, insurance and other nondiscretionary overhead items don’t drop, any decrease in revenue comes 100% out of your profits.)

Why is this not a cause for concerted analysis, diagnosis, and corrective prescription? (Were this the case in our own business, we would find it a cause for real soul-searching.)

Alas, the answer to that last question may fall more into the realm of psychology than economics, so I will not venture an explanation, but if looked at solely from the clients’ perspective, the most likely reason may be self-evident: They don’t value what their law firms are doing as highly as the firms themselves seem to.

Could it be that the clients are expecting “service”–that their business problems will be addressed and solved–and the lawyers are fixated instead on the magnificence of the practice of law?

What does your strategic plan have to say about this? What do you have to say about it? Does your firm exist first and foremost to serve clients its partners?

Surely diminished realisation is as a result of firms’ official fees increasing year-on-year, while in fact all major clients (a) negotiate substantial discounts from the ‘rack rate’*; and (b) impose ‘outside counsel’ policies which also serve to restrict the amount of work which is billable (for example, precluding charging for travel time – time in which the firm will still be losing billable hours in which otherwise associates would be working on other matters).

What have I missed?

* The official or advertised price of a hotel room, on which a discount is usually negotiable. Example: “many hotels have upped their rack rate so they can continue to give monumental discounts”

“We raise our rates knowing our clients will give us a big haircut” is precisely the conventional wisdom about this waltz that I wanted to try to dig into and see if there might be more to it than that. Some other industries follow an even more extreme version of overpricing/discounting (department store apparel, anyone?) but in others prices are strictly non-negotiable, at least not on anything other than an extremely high-volume basis (Bloomberg terminals, infamously, but also cable TV, desktop software, theater/concert/opera/movie/sports tickets, electricity, etc.)

Nor is our industry monolithic on this; I don’t think it would be a very promising gambit to ask Wachtell for a discount on their M&A representation, or virtually any of the Global Elite in one of their marquee practice areas.

Some interesting stats on this in a piece by Roy Strom on April 23 in The American Lawyer on US law firm discounting practices –

“Data from Thomson Reuters Peer Monitor shows standard rates have risen by nearly 40 percent since 2007, which is nearly twice the rate of inflation during that period. But that doesn’t mean much on its own, considering there has been a corresponding fall in the portion of that rate that actually gets paid. Realization rates have fallen from 92 percent in 2007 to a record-low 81 percent in 2018, Thomson Reuters reports.

The math works out like this: A $380 standard rate in 2007 turned into $350 in revenue that year, while a $525 standard rate in 2018 equated to $425 in revenue, according to Thomson Reuters data. That 21 percent rise in the actual cost-per-hour of legal work is almost perfectly in line with 11 years of inflation.”

My guess is that the wider spread between rack and realised rates reflects several factors –

1) increased price discrimination by law firms given that some clients have become more willing and able than others to push for discounted rates (which, of course, is not at all the same as saying that those who don’t do so don’t care about cost….);

2) increased use of AFAs – I suspect that an inflated rack rate is less likely to be negotiated down if it’s only being used for shadow billing, but using that rate in shadow billing can then make the fixed fee look “better value” given how ingrained it is to think of time-based billing as the norm;

3) the fact that heavy discounts have become commonplace may now be self-reinforcing (with problematic implications…).

The bigger theme here is the difficulty in defining or recognising “value.”

This is, of course, the problem with lawyers. They want to be lawyers, not business people. They value legal acumen over business acumen. They do not want to manage people, they do not want to be managed, they do not want to do anything that lacks intellectual stimulation, and they want to remain focused on law. Any lawyer who has spent time in government service will tell you it was the best job of his life (other than the pay) because he got to be a lawyer. No marketing, no finicky clients, no one telling him what to do, and depending on the role, lots of time spent in court.

Of course, there is also the tension with billable hours. Back when I was in private practice at a large law firm, I suggested to a client than in any litigation we should look at damages and business impact first so the client could decide whether to settle the case early and for how much. The client agreed. The firm was appalled. After all, a creative legal idea and long fight could win the case for the client (and win fees for the firm). An analysis of the business impact was neither legal in nature more likely to yield high fees.

I left big law not long after. And now I have the best job in the world – as a government lawyer.

Agreed. Most highly educated white collar non-business skilled professions (Doctors, for example) would agree with you. Many would prefer only practice medicine and not worry about the business.

Hear, hear. If a firm makes it clear to its clients (as mine does) that one of its goals is to help its clients spend less on legal fees, and if it can demonstrate to its clients that it can accomplish that goal while competently representing the client, it will presently have all the work it can handle.

TLDR? Peter Drucker: The purpose of a business is to create a customer.

Another perspective from an in-house lawyer (financial services): the value added by outside counsel keeps declining as they lose contact with our business. The escalation of rates has caused us to hire many excellent lawyers who deal with the minutiae of the business as well as difficult legal issues. As a result, we rarely retain outside counsel, and when we do, we spend a lot of time now educating our outside counsel on how transactions and operations work and the legal issues. It’s almost like a solicitor briefing an English barrister. We need the outside counsel more to validate our work or to provide no-name access to regulators than we do for legal analysis, unless a new area of business opens up. And thus we press back on billing for anything but the top-level partners. And don’t tell your law firm clients that they need to get in closer with us to learn the business — we don’t have the time and don’t need the distraction.

Would it be helpful to explore what it is that the firm serves, and to whom? That is, as seen by an outside client, the firm provides professional services. Those professional services could be focused, say on high-end legal analyses, or they could be general, for example support for disaster recovery on top of legal services. But, endeavoring to see this from the point of view of the specialist partner, could we not say in another context that the firm also provides support and services to the partners so that they efficiently may serve the outside clients? Only if the provision of professional services meets the needs (including of cost) of the outside client(s) will there be the resources to provide efficient support to the specialists. But (inertia aside) unless the specialist sees the firm adding value to their practice, why would they remain in a firm?

Mark: Gifted and astute, as usual. Focusing on what the firm provides to its partners is a dimension of “services” that I had not thought about. It prompts two questions in my mind: First, in classic Coasean fashion, it may explain why (at least from the partner/practitioner’s perspective), the firm exists: That is to say, why there is a “firm” and not a web of contractual relationships. Second, I wonder whether most partner/practitioners appreciate what the firm provides them as opposed to what they, Masters of the Universe one and all, can do on their own. Three guesses as to what our experience leads us to believe.

Bruce: One of the things (I see these as matters of substance, so “things”) that a firm can provide is a history of excellence, a reputation for probity and value, a guarantee of integrity. In short, a heritage for which the partners (and all the team, really) need to exhibit a sense of stewardship. Non sibi …