To help answer that we need to introduce a few other potential values. In other words, if not shareholder value (PPP to you and me), then what?

Before proceeding, let me specify two things I am not saying:

- Do not mistake my reflections for nostalgia. The good old times were not always so good. Neither is it the case that we, like every generation that has ever come before in the history of humanity, are more enlightened than anyone has ever been. “How could they have thought/done/believed that?” Philip Roth labeled this the “ecstasy of sanctimony.” Yes, by and large we have made progress, but perhaps not linearly across all fronts.

- Do not for a moment think I’m casting aspersions on powerful business strategies or disciplined execution. But there are worthy and unworthy strategic goals, and the ends do not always (ever?) justify the means.

With that out of the way:

Last week David Brooks of The New York Times wrote a column exhuming the thought of the largely forgotten Harvard philosopher, Josiah Royce (1855-1916), who emphasized the virtue of devoting oneself to a cause larger than self. Royce’s parents were failed 49’ers:

Out on the frontier, he had seen the chaos and anarchy that ensues when it’s every man for himself, when society is just a bunch of individuals searching for gain. He concluded that people make themselves miserable when they pursue nothing more than their “fleeting, capricious and insatiable” desires.

So for him the good human life meant loyalty, “the willing and practical and thoroughgoing devotion of a person to a cause.”

Royce tagged this ultimate virtue “loyalty,” a word which today for some has taken on unfortunate connotations, so you can substitute “devotion” or another moniker of your choice; as they say, it’s the idea that counts. Royce may have seen this coming over a century ago when he distinguished virtuous from evil “loyalty:”

Of course, there can be good causes and bad causes. So Royce argued that if loyalty is the center of the good life, then we should admire those causes, based on mutual affection, that value and enhance other people’s loyalty.

We should despise those causes, based on a shared animosity, that destroy other people’s loyalty. If my loyalty to America does not allow your community’s story to be told, or does not allow your community’s story to be part of the larger American story, then my loyalty is a domineering, predatory loyalty. It is making it harder for you to be loyal. We should instead be encouraging of other loyalties. We should, Royce argued, be loyal to loyalty.

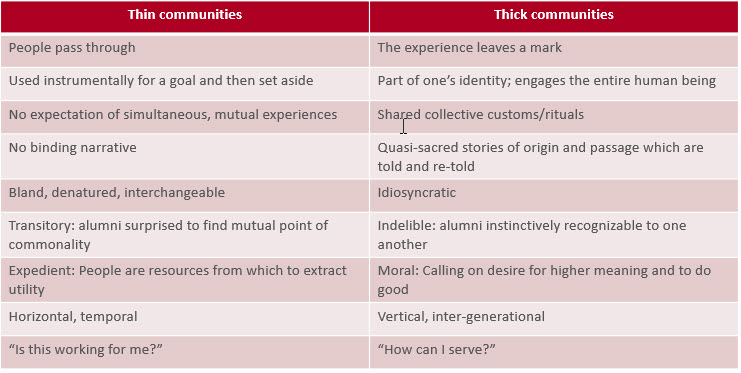

Another model for contrasting our two opening stories is expressed in terms of thick and thin communities. This is the difference:

For years (decades?), I have struggled to comprehend what people are talking about when they invoke their firm’s “Culture.” The thick/thin community model may be the closest I’ve come. Not all “cultures” are worthy, and your firm can be a hotel for lawyers on one hand or a bound community of devoted participants striving to build something greater than they found. “Stewardship” in the most expansive sense: Leaving this place better than you found it.

What is the nature, then, of your firm?

Nicely framed Bruce – thank you