My title for today steals literally from Ronald Coase’s legendary 1937 paper of the same name, which gained Coase the Nobel in Economics in 1991. The paper, barely over a dozen pages long, asks the question, childlike in its simplicity, “why do firms exist?” In other words, given that essentially any and all tasks can be contracted out to people who are (pace Adam Smith) already the best at providing the goods or services they do–powerfully more true today than 80 years ago–why would anyone choose to hire people full-time instead?

Coase’s more formal statement of the question is “Why and under what conditions should we expect firms to emerge?” And his answer centered on transaction and related costs such as those incurred in search and finding information, policing and enforcement, confidentiality and trade secrets, and constant bargaining and negotiation. (Coase was born in Willesden, London in 1910 and died in Chicago in 2013 at age 102, having lived, one must imagine, a stupendously satisfying life.)

But today we’re actually not writing about the “nature” of the firm in the Coasean sense at all. Rather, I want to open a discussion into “What are firms for?,” or what is the nature of firms’ obligations to their owners, employees, clients, competitors, markets, and communities.

Let’s begin in the middle, as it were. Two recent articles juxtaposed profoundly different concepts of what the nature of a law firm is in the 21st Century. The contrast could not be more extreme.

We’ll start here:

- “This move will act as a catalyst to make people in Magic Circle or Silver Circle firms analyze whether there are better long-term prospects for them in a U.S. firm,” said one private equity partner at a U.S. firm. “This is a starting point for other people to work out their own position.”

- One former Freshfields partner suggests Kirkland’s strategy is more nuanced than a simple case of acquiring top talent and a roster of portable clients, and compares the firm’s approach to Google and Facebook snapping up startups before they become competitors. “U.S. firms tend to be highly strategic,” the former partner said. “They’re capable of hiring people from a competitor just to destabilize them. If you’re Kirkland and you have a global PE business of, say $300 million, with five or six key clients, it makes sense to neutralize the competition to protect the franchise. Spending 10 bucks to save $300—why not?”

And then we have this, from the NYT’s 18 January 2019 obituary of John Merow, Managing Partner of Sullivan & Cromwell from 1987–1994 (Merow [89] and his wife Mary Alyce [85], died tragically in a January 12 fire in their River House [Manhattan] apartment).

[The co-author of a book on Sullivan & Cromwell] said Mr. Merow had loosened policies and practices at the firm. But the traditions of lawyerly etiquette and camaraderie prevailed, at least in public. After The American Lawyer quoted Mr. Merow as saying of rival firms, “We really don’t think that, all in all, Cravath or Davis Polk has quite the range of strengths we do,” he felt obliged to apologize to his counterparts — Samuel Butler at Cravath, Swaine & Moore and Henry King at Davis Polk & Wardwell.

These two stories do not recount what could be characterized as differing approaches to or opinions on a topic; they embody two strikingly incompatible world-views.

When our world has changed this much in the span of less-than-a-career, it may behoove us to examine what we have gained and what we have lost.

Our world of Law Land, cloistered as we sometimes think it is, exists of course in a far larger world of finance, commerce, and received wisdom about how enterprises should be governed. Over the past fifty years or so, it’s safe to say that the “Chicago”/Milton Friedman theory of firms has triumphed, as embodied in the curricula of most business schools, widely practiced (if sometimes criticized) practices in finance and corporate governance, and even Delaware corporate law.

Firms exist primarily to maximize shareholder value, and the primary internal motivational tool has been incentive compensation, particularly at the executive level. The crux of the employer/employee relationship has shifted from one of trust, loyalty, and mutual obligation to a purely transactional, “what have you done for me lately?” mindset, where as soon as the perceived cost/benefit of the situation turns even momentarily negative, you are at liberty without a second thought to part ways. Loyalty–from employer to firm and vice versa–is quaint.

The results are self-evident. For example, according to the Economic Policy Institute (a think tank explicitly founded to provide a voice for lower- and middle-income workers, but a reliable source of factual data nonetheless):

In 2017 the average CEO of the 350 largest firms in the U.S. received $18.9 million in compensation, a 17.6 percent increase over 2016. The typical worker’s compensation remained flat, rising a mere 0.3 percent. The 2017 CEO-to-worker compensation ratio of 312-to-1 was far greater than the 20-to-1 ratio in 1965 and more than five times greater than the 58-to-1 ratio in 1989 (although it was lower than the peak ratio of 344-to-1, reached in 2000). The gap between the compensation of CEOs and other very-high-wage earners is also substantial, with the CEOs in large firms earning 5.5 times as much as the average earner in the top 0.1 percent.

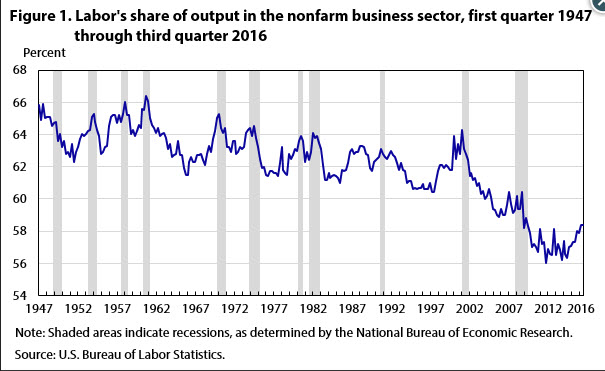

Or if you’d prefer to look at the share of national income that goes to labor, the BLS has that data for you:

If you wanted to summarize the past 15 years or so of this data in shorthand fashion, you might say “it doesn’t pay to be a worker.”

Looking at this more dispassionately, one has to acknowledge that whatever the sins or virtues of the shareholder-value-maximization school, we as an economic nation seem to be pursuing it successfully.

But is this all there is, or should be, to a firm? To a law firm? Is “hiring people from a competitor just to destabilize them” fair game, nothing-to-see-here-folks-move-along? Is it justified or worthy behavior in the name of “protecting the franchise,” as our observer would have it?

Nicely framed Bruce – thank you