Having discussed the Citi/Hildebrandt annual client advisory, we now turn to the Thomson-Reuters/Georgetown Report on the State of the Legal Market for 2018.

If Citi’s editorial tone tends to be rather celebratory of good news, Thomson-Reuters’ tends in the opposite direction and highlights blind spots or questionable assumptions in the received industry wisdom. Together, I suppose you could say they achieve a realistic mean, but because by nature I view one of the signal cardinal sins in business as that of complacency and (likewise) because I find myself always asking, “What are we missing here?,” this report is much more to my taste.

Certainly, on this approach, its opening does not disappoint.

When faced with mounting evidence that our traditional way of looking at a problem is no longer satisfactory, most people would agree – at least in the abstract – that it makes sense to examine our underlying assumptions with a view toward possibly changing the model we use to think about the issue. Unfortunately, such openness to change frequently runs counter to our natural instincts. As psychologists have now amply demonstrated, we humans have a tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms our preexisting beliefs or hypotheses – a cognitive tendency that is referred to as confirmation bias. And there is some evidence that this cognitive bias can be especially strong among professionals who have been trained to accept a particular point of view and who have a fear of being regarded as illegitimate by their peers for questioning long-established principles.

They then recount the priceless history of modern medicine’s stalwart refusal to abandon its belief that ulcers were caused by stress and diet and best treated with rest, antacids, and bland food. As we now all know (I think!), in 1982 a pair of Australian physicians, Robin Warren and Barry Marshall, demonstrated the cause was instead a bacterium, H. pylori–a discovery for which they won the Nobel Prize in 2005. Yet many practitioners never wholeheartedly adopted the new reality. (Indeed, Dr. Marshall, in what can only be described as “heroic science,” ultimately drank a beaker laced with H. pylori, developed an ulcer, and self-medicated, effectively, with antibiotics. Skeptics remained.)

This of course recalls Max Planck (1858-1947, and 1918 Nobel physics prize winner for quantum theory), who gave us the timeless observation that “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it,” which has been conveniently shortened to “Science advances one funeral at a time.”

Back to the Thomson-Reuters report.

They diagnose the 2018 figures as “somewhat mixed,” with the upside being a modest increase in demand and growth in worked rates (“worked” rates in their parlance are agreed-to rates after application of any upfront discounts), plus a small uptick in productivity, yielding overall average revenue growth of +5.5%. The downside is our by-now-familiar nemesis and companion, dispersion of results among firms: Performance by firms in the AmLaw Second 100 and some others “were well below the market averages, [which] raises the interesting question of why different parts of the market are performing in strikingly different ways.”

Indeed. And after rehearsing their statistical findings, the remainder of the report is devoted to just that topic.

They essay three primary reasons why the traditional and very durable mental construct many of us have of a rising tide lifting all firms is now obsolete:

- The market is more transparent than it ever was, thanks to dramatic growth in trade publication coverage of Law Land, social media, and other sources of analysis.

- Technology; a compulsory entry on this list.

- And the Great Meltdown’s after-effects, including the oft-remarked but no less real for that shift from a seller’s to a buyer’s market. In particular, what clients mean when they say they expect “value” from their law firms has changed. It is no longer (merely) superb legal advice, it’s “higher levels of predictability, efficiency, and cost-effective [delivery,] quality being assumed.”

Finally, clients are taking a more transactional (they don’t use the word “expedient” but next year they might) approach to outside counsel relations in general, including being far more willing to unbundle their work, or disaggregate suppliers (certainly for larger matters) and to move away from their traditional base of outside firms to smaller firms and/or New Law. All this has intensified competition among law firms and has made it clear, lest you had any doubt, that the only way for your firm to grow revenue is to take it away from another firm. While the vast majority of the economy by far is in sectors that long ago became mature enough to evolve into battles for market share, this is a new and potentially mystifying experience for Law Land.

Did we mention that New Law has arrived?

The Report pegs New Law revenue in 2018 at $10.7-billion, which may sound nonthreatening next to law firms’ aggregate revenue of approximately $285-billion, but consider that (a) there’s a “multiplier” applied to New Law spending if you’re asking the question, “How much of this comes out of the hide of traditional law?” (we have estimated that multiplier at about three, and you’re welcome to prefer two or four, but you are not permitted to prefer one as the multiplier); and (b) New Law’s revenue–counting standalone companies only and not “captive” offshoring or near-shoring operations under the umbrella of law firms themselves–is growing at nearly 25%/year.

Do that for three years in a row, and things will have (just about) doubled. After six years, quadrupled. That would put NewLaw’s revenue in 2025–tomorrow in the history of major industry life-cycles–at $40-billion. If you’re not noticing now, would you notice then?

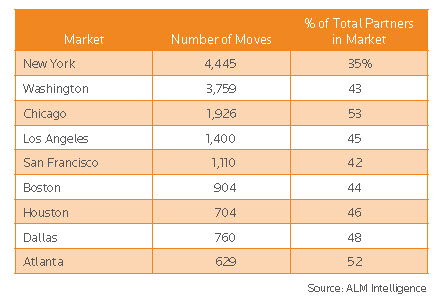

Let me share with you a stunning table from the report, which details the number of lateral partner moves from 2010 to 2017 in nine leading metropolitan areas in the US:

Need I go into excruciating detail? In Atlanta and Chicago, it’s more than half of all partners, and in every other market save New York–which is constrained by its own peculiar, rigid, and super-hierarchical pecking order–it’s darned close to half. (Give it one more year to run, shall we?) With magnificent understatement, the report summarizes this: “Clearly, the competition for lateral talent is at an all-time high.”

The question then, is whether this is a good thing or a bad thing. If you prefer highly liquid talent markets and a rich array of personal options over institutional memory, deep trust within a firm, and collaborative team-building over time, you like it. And vice versa.

Backing off from that existential foray into your indifference curves, let’s ask a simpler question: Is it working for the business of law? Is it helping us deal with the changed landscape since the Great Meltdown? Thomson-Reuters thinks not, and I invite you to find the flaw in their view (emphasis mine):

Firms have responded to this increase in competition in a variety of ways – by enhancing PPEP by reducing the number of equity partners, by increasing spreads in partner compensation, by raising associate compensation to retain promising young lawyers, and (as noted) by pursuing mergers to make their market footprints more competitive. Ironically, these steps have sometimes led to more instability rather than less.

I won’t recapitulate our views on the lateral partner recruiting arms’ race here, but doesn’t this all constitute a massive game of zero-sum revenue musical-chairs pursued at tremendous transactional cost in real $$ and senior-level management distraction?

Something subtler is going on: The traditional levers of financial management and revenue/profit growth don’t work they way they used to. This can make it hazardous to your law firm’s health to assume they still work and continue to rely on them; the mental image springs to mind of a comic pratfall scene where the steering wheel and gearshift come off into the hands of the hapless driver.

Consider: What is the “right answer” to each of the following management decisions:

- Raise rates and price aggressively? Or respond to clients’ voiced preference for economies?

- Invest more than the other guys in work flow process optimization and technology to steal a march in efficiency, or wait to see what works before making a serious commitment?

- Expand geographically to offer clients more services in more places or focus on your core markets?

- Participate gleefully in the lateral arms’ race or save your powder?

- Increase associate compensation to retain the “best and brightest” or face the music of career butterflies?

- Is leverage friend or foe?

We’ll stop now.

The report rightly opened with a narrative about how to respond when faced with increasing evidence that one’s traditional way of looking at a problem no longer suffices. In that spirit, then, let us–hand-in-hand with the report’s authors–suggest a new mental construct for understanding the dynamic forces at play among law firms.

Our hypothesis is that the days of one unitary market for “law firm services” has disappeared. Some firms–a small minority–are in one type of business, but everyone else is in an entirely different business. Note I did not say different business “model,” but different “business.” Firms in each business compete with one another, but not with firms in the other business. Call them the Maroons and the Greys.

Clients needing the services of a Maroon wouldn’t even glance at a Grey, and vice versa. Maroons compete with Maroons, and Greys are no “substitute” (economic sense) for what Maroons can do. (Simple analogy: Uber, Lyft, and yellow cabs are substitutes for one another; Uber and walking probably aren’t.)

We will have much more to say about the Maroons and the Greys here at Adam Smith, Esq. in future (and our friends at T-R generously gave me credit by name for this construct–see fn. 28 on pg. 17), but in the meantime let’s give Thomson-Reuters the last word: Surviving as a going firm, much less thriving and prospering, all begin with a frank and unblinking analysis of which business your firm is in. This is anything but an “academic” exercise:

The strategic decision-making process described above may make perfect sense in the abstract. But the question remains whether a majority of firms will be able to make the honest assessments and strategic judgments necessary to compete effectively in the new market for legal services. Sadly, that remains an open question and an especially important one for the vast majority of U.S. law firms whose practices fall primarily in the [vast majority of firms business] category described in our suggested market model. The problem is not so much that law firm leaders fail to understand the challenges their firms face or the steps they need to take to remain competitive, but rather the resistance that is often mounted by firm partners to the changes that are required.

Will we follow the doctors who resisted the new learning about ulcers for a quarter of a century and more? And if we take that path, how well will we be serving our clients?

And it all starts with knowing which business you’re actually in.