Michael Lewis’ 2004 bestseller, Moneyball, subsequently made into a movie in 2011, has entered the vernacular. We have Moneyball for government, Moneyball for writing (and awarding) grant proposals, and, yes, Moneyball for lawyers. And its basic premise is hard to argue with: Data–especially “Big Data,” where you can find it–if properly analyzed, doesn’t lie. Another factor has, I suspect, heightened its impact on business, its visibility in popular culture, and its entry into the common parlance of conversation: Lewis published the book right around the same time behavioral economics, with all its learning about systematic biases human judgment and intuition, also came to the fore (loss aversion, anchoring, confirmation bias, heuristics, framing, and all the familiar rest of it).

The combination is killer: Data can tell stories you never knew were there to be discovered, and your own gut can lie to you about reality.

So what more is there to be said?

Lots, it turns out.

Our texts for today are a two-part interview series in the McKinsey Quarterly featuring Houston Astros general manager Jeff Luhnow after his team won the 2017 World Series. (I. How the Houston Astros are winning through advanced analytics, June 2018, and II. A view from the front lines of baseball’s data-analytics revolution, July 2018) Four years earlier they had lost whopping 111 games in the 162 game season (68%).

Nor did they do it through check-writing prowess: Their payroll was 18th of the 30 major league teams, and almost 50% ($118-million) less than the highest spenders, the LA Dodgers.

Putting it mildly, this turnaround was no accident.

Now, you may think you know everything you need to about the Moneyball approach–and have concluded it could never apply to your firm because (a) lawyer performance isn’t reducible to data; (b) even if it were we haven’t collected the data; (c) if we wanted to collect “the data” we’d have no idea exactly what data we should be looking for or tracking; (d) even if we knew what to get, had it, and could evaluate lawyers using it, they’d never accept it because human judgment is, y’know, ineffable; and (e) you get the idea.

When Luhnow arrived at the Astros in 2011 the situation was very similar.

Quarterly: What were the analytics strengths and weaknesses for the Astros when you joined them in 2011?

Luhnow: There really was not any focus on analytics at all. It was a traditional scouting organization. … [I]n terms of the analytic capabilities of the organization, if I were to rank it, Houston would have been in the bottom five for sure.

Quarterly: Were the existing personnel receptive to your changes?

Luhnow: No. There are hundreds of people that work in a baseball organization, including coaches, scouts, and hundreds of players that are signed at any one point in time. They did not accept it (emphasis supplied)

So how did Luhnow push this cultural boulder uphill?

That’s where the story gets interesting and, I hope, instructive.

Major League Baseball isn’t Big Law, but you can feel viscerally how the organization took to the changes analytics introduced.

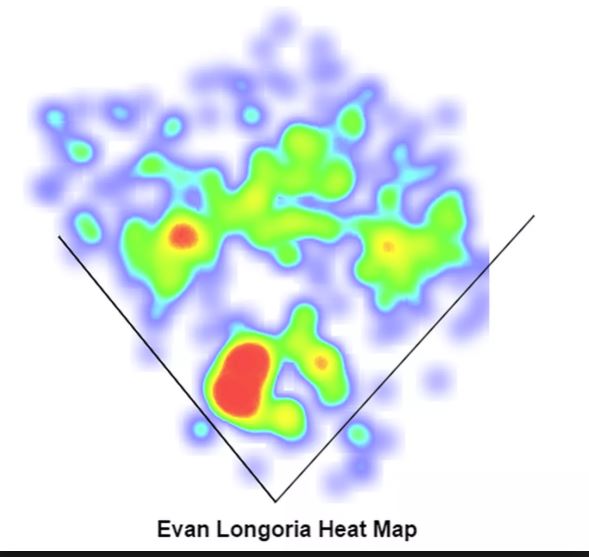

Quick digression on one of the techniques of analytics in MLB: Because you have data on where any given batter has traditionally been able to hit the ball effectively [down the third base line, through the gap between first and second base, etc.], you can “shift” your fielders defensively to be in position to anticipate that batter’s favorite probability dispersion of hits. This obviously moves them away from the traditional position where, say, the shortstop “ought to be.”

Here’s a real heatmap of a hitter’s favorite target zones:

Now the following should make more sense.

Interesting to think about the future of data analytics in Big Law in connection with your prior post on recruiting and maintaining talent. And also with an idea ASE has introduced once or twice (e.g., Aug 6,2015): what would R&D look like in the context of Big Law?

Mark: Point very well taken. I believe the consummate core competence of a superb law firm–above every other–is winning the war for talent, a/k/a recruiting, retention, and professional development. And that’s an area where blessedly psychologists, HR professionals, organizational dynamics gurus, and many many other disciplines have been collecting data for decades. In other words, there may already be–should be–“Big Data” that law could draw on to help make its decisions here more optimal.

Add to that the building wave of AI capability in Law Land and it seems perfectly obvious to me that the partner-material lawyer of 2020 or 2025 will have quite a different dispersion of personality characteristics than that of 2010 or 2015.