But there’s more, and it comes back to clients. You are in the distinct minority if you haven’t heard this observation or its equivalent: “I’ll happily pay $1,000/hour for the partner who’s the go-to name on this kind of stuff; it’s the $350/hour associates that are killing me.”

Or: “We’re partner-service driven.”

Or: “15 minutes with [Dave] is worth all day with someone else.”

Or even (from a managing partner): “There is literally no hourly rate high enough to capture the value of [so and so superstar’s] expertise; how on earth can I charge for this guy?”

All these remarks point in the same direction, and higher leverage is not it.

Finally, for those of you who harbor a secret fear that lower leverage –> lower profitability, I have one word for you: Wachtell.

I mentioned a first whiff of data in support of this hypothesis. It arrived earlier this month in the form of Thomson Reuter’s first-ever Dynamic Law Firms Study: What Makes a Law Firm a Dynamic Industry Leader?

Here’s the executive summary of the report:

The latest study from Thomson Reuters Legal Executive Institute highlights a few areas where some firms have been able to set themselves apart, and provides some guidance as to areas where law firms looking for additional growth may want to focus.

The 2017 Dynamic Law Firms Study is based off an analysis of firms participating in Peer Monitor, and identifies those law firms that have seen best-in-class growth over a three-year period in the key areas of revenue per lawyer, overall profits and profit margin. We conducted an analysis of the entire Peer Monitor universe, calculating the compound annual growth rates for each firm on each of these metrics. Firms were then scored based on their performance on each metric, and placed into quartiles based on their composite score. The upper performing firms — those with the best composite scores reflecting strong growth in these areas — became our Dynamic Law Firm population. The lowest quartile firms — those who have experienced slower growth in these areas or in some cases even contraction — became our Static Law Firm population.

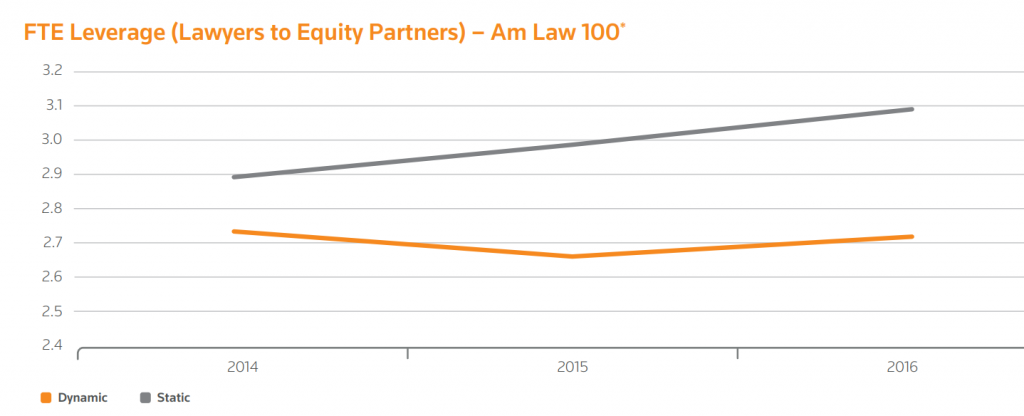

Now, then: Here’s the data on leverage among the AmLaw 100 “dynamic” (orange) and “static” (gray). Not only are the dynamic firms operating at about 10% lower leverage (2.7:1 vs. 3.1:1), they’re not growing it–and the static firms are.

Could this be a leading indicator of the death of one of the most time-honored of law firm financial tuning tools? And what would it mean if it is?

Well, just for starters it might mean firms would want to invest more in junior talent–recruitment, retention, training, enrichment–as the beginning of a return to the days when partners could welcome first-year associates with a straight face and say, “We hope each and every one of you makes partner.”

Isn’t that, after all, the way most companies in the economy work, or would like to work? To keep people as long as they can, given continuous and appropriate improvements in performance? To become a firm of loyal team-mates?

What would be wrong with that? It might even lure more highly-qualified college grads back to the doors of Upper Crust law schools.

Excellent piece Bruce, uncompromisingly hitting the mark. One question from me: You state “NewLaw is now at least a $25-billion/year business (US domestic market only)”. Based on the size of the big NewLaw enterprises of which I am aware, I find this figure hard to agree with, e.g. the reported annual turnover of Axiom Law is $300m. Of course, the definition of the industry is key. My January 2015 post is a comprehensive attempt to define NewLaw: http://www.beatoncapital.com/2015/01/fresh-thinking-evolving-biglaw-newlaw-continuum/. Welcome your comments. All the best George

I wonder if there are ties to ASE’s “A New Taxonomy: The seven law firm business models,” that are worth considering in regard to “leverage?” In consulting engineering, there are two, quite distinct manners of generating income: a) “extension of staff” and b) specialist consulting. The former is the provision of qualified and supervised, usually low- to moderate-experience staff who undertake functions that Client *could* execute via full-time, in-house staff if they saw that as the best use of resources. The latter is the provision of highly experienced specialist engineers who develop the conceptualizations for, then oversee the execution of complex programs for which there are “existential” implications for client (say, a water-retaining dam upstream of population or a sensitive ecological reserve), and “stamp” the final designs as compatible with their responsibilities to both Client and the public. Engineering consulting firms routinely leverage the extension-of-staff function, but the fees for the engineering boffins are already so high (relative to industry) that there is little elasticity and so limited capacity to provide marginal revenue.

In these conditions, an engineering firm must make a fundamental decision about the nature of its business. Although many engineering firms will assure you that they can do it soup-to-nuts, it is of no use, or even interest, to Client A that Consultant X has 87,000 employees world-wide. Readers here can easily match up Bruce’s “New Taxonomy” categories with the role of leverage in terms of how the law-firm models relate to “extension of “staff” versus boffins.