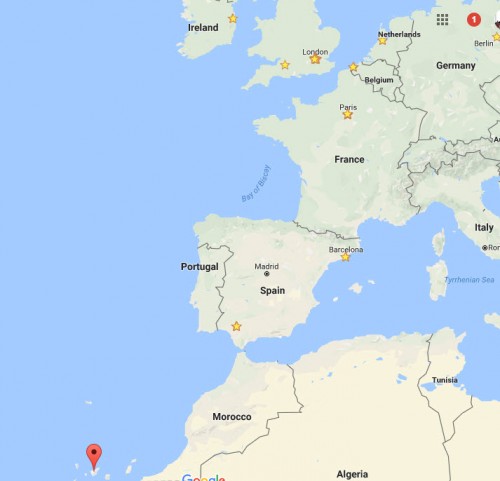

Forty years ago last March what remains the greatest disaster in aviation history occurred at Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Human error was the primary cause.

583 people were killed (61 survived, or a 90% fatality rate) when two Boeing 747s – one belonging to KLM, trying to take off and the other to Pan Am, taxiing – collided on Los Rodeos Airport’s single runway. Pan Am flight 1736 had originated in Los Angeles and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines flight 4805 in Amsterdam.

As usual with serious aviation or industrial accidents, several things went wrong in a sort of Faustian cascade that ultimately led to the disaster: But there was one overwhelming primary cause, which we’ll get to.

The lesser but still highly material problems:

- Thanks to a separatist bomb being set off in the terminal at the far larger Las Palmas Airport on Gran Canaria, Tenerife was pressed into service to accept diverted planes and the small airport was seriously overcrowded, its aprons and taxiways full of parked aircraft. This meant the runway itself had to do double duty as a taxiway.

- A dense fog descended shortly before the accident, limiting visibility to 1,000 feet or so at best.

- Air traffic control (ATC) terminology and phraseology had not yet been fully standardized.

- And “crew resource management” training did not yet exist.

A brief word on the last point, not self-explanatory to the uninitiated. Before Tenerife–and the following year’s crash of a United DC-8 holding on approach into Portland, Oregon which ran out of fuel while the crew was trouble-shooting balky landing gear–this concept was unknown. Cockpits were authoritarian environments where the captain’s word and judgment ruled. It was out of bounds for a co-pilot or first officer to so much as point out contrary instrument readings, much less ask the pilot if he were certain in his judgment or, God forbid, disagree.

The story of the United/Portland crash is instructive on how “crew resource management” was introduced into aviation.

United 173 left Denver about 2:47 pm with 189 people on board; the estimated flying time was 2 hours and 26 minutes. The total amount of fuel required was 31,900 pounds, and 46.700 pounds were on board the DC-8 at Denver gate departure.

The cockpit crew was highly experienced: Captain Malburn McBroom (52), had been with United for 27 years and was one of the most senior pilots at the airline; First Officer Roderick Beebe (45) (13 years at United) and Flight Engineer Forrest Mendenhall (41) (11 years).

As the landing gear was being lowered on approach into Portland, there was a strange vibration and the aircraft yawed; the indicator light for “gear locked” also failed to come on. The crew requested a holding pattern to diagnose the problem. With flaps down at 15° and the gear lowered, fuel consumption rose to abnormal levels during the hour-long holding maneuver. Meanwhile, none of the three in the cockpit monitored fuel levels. As they finally entered their final approach for an emergency landing at Portland International, they lost the ##1 and 2 engines to flameout and, flying low and slow, crashed into a heavily wooded suburban area six nautical miles short of the airport; there was no fire. Mendenhall died but Beebe and McBroom survived, albeit with serious injuries, as did the majority of the passengers (8 killed, 21 seriously injured).

The NTSB’s determination was that the primary cause was McBroom’s failure to properly monitor the fuel level and failure to respond to the other cockpit officers’ advisories about critically low fuel, because he was preoccupied with the landing gear malfunction and preparing for an emergency landing. The first officer and engineer was also criticized for not “successfully communicat[ing] their concern to the captain.”

Here are some excerpts from the cockpit voice recorder (emphasis mine). If you could write a more compelling real-world-dialogue study in miscommunication, you may be the next Elmore Leonard.

About 1750 [25 minutes before the crash], the captain asked the flight engineer to “Give us a current card on weight. Figure about another fifteen minutes [before landing].” The first officer responded, “Fifteen minutes?” To which the captain replied, “Yeah, give us three or four thousand pounds on top of zero fuel weight.” The flight engineer then said, “Not enough. Fifteen minutes is gonna — really run us low on fuel here.”

At 1806 [9 minutes before the crash], the first officer told the captain, “We’re going to lose an engine….” The captain replied, “Why?” At 1806.49, the first officer again stated, “We’re losing an engine.” Again the captain asked, “Why?” The first officer responded, “Fuel.“

1808:42 [six minutes before the crash]- Captain: “You gotta keep ’em [the engines] running….”

Flight Engineer: “Yes, sir.”

1808:45 – First Officer: “Get this…on the ground.”

Flight Engineer: “Yeah. It’s showing not very much more fuel.”

At 1813:38, the captain said, “They’re all [four engines] going. We can’t make Troutdale.” [a small airport on the final approach to PDX] The first officer said, “We can’t make anything.”

Back to “CRM:” Its primary goal is to develop situational and self-awareness, flexibility, adaptability, and communication. It:

aims to foster a climate or culture where authority may be respectfully questioned. It recognizes that a discrepancy between what is happening and what should be happening is often the first indicator that an error is occurring. This is a delicate subject for many organizations, especially ones with traditional hierarchies,

The human factor I mentioned back at Tenerife? The human in question was the KLM captain, Jacob Veldhuzen van Zanten, described as “a seasoned pilot so popular and photogenic” that KLM featured him in its promotional campaigns, he was KLM’s most experienced pilot. In fact, when news of the disaster reached KLM headquarters, they tried to reach van Zanten to get him to the scene to investigate.

Both standard corporations and partnerships would benefit from reading and thinking about the work of Charles Perrow on complexity in large-scale undertakings. His magnum opus is Ordinary Accidents. Perrow’s thesis is that the human mind is not evolved to deal usefully with nonlinear systems, and if the nonlinear systems include feedbacks, then the human mind performs very poorly indeed at predicting what the consequences of any decision may be. It is ordinary for accident reviews to determine that the dominant pathways for catastrophic accidents is human error, but Perrow argues that this is an unjust and unjustified conclusion in many systems that include, indeed may be predicated on, nonlinearity. The effect of the additional drag from angled flaps on fuel consumption in the UA flight considered would be an example of a nonlinear effect that the Captain did not recognize and account for. His crew saw the effect in fuel consumption, but did not understand the aerodynamic driver in a timely fashion or work it’s impacts into their decision-making until it was far too late.

Leadership, and all those generally concerned with how their organization may respond to a crisis, would do well to take Perrow’s analysis seriously. I am certain that – however much attorneys may have been trained in systems of formal logic, there are circumstances in which complex business situations – formally legal and also business – become highly nonlinear, and what this means for stability of the organization should be a matter of interest, or even concern.