I’ve been thinking a lot lately about litigation.

It’s been one of the two major locomotives driving revenue and profit for BigLaw for the past 50 years or so–the other being transactional or corporate work–and has customarily provided 25–60% of a firm’s revenue; call it 25-40% for the median firm. If you look at a wide sample of firms’ lawyer headcount by practice area, rare is the firm that strays too far from the range of about 30/30 to 40/40 litigation/transactional.

But litigation has been the sickly child for the past decade or so.

This is the first in a multi-part series asking the question, “Is litigation in long-run secular decline?”

When we bat around the term “litigation” in this series, we should be more precise: Here are some of the things we mean and some of the things we do not mean.

- First off, we mean revenue from litigation as a practice area for law firms, not the number of disputes or filed claims, or their notional value, in the US or global economy.

- Second, as with almost all trends and developments in our industry these days, the pleasure and pain of this has not been and will not be distributed evenly. Some categories of firms are suffering a lot more than others.

- Third, we make a vivid distinction between the Big Bad matters–the Deepwater Horizon, the VW emissions scandal, the Apple vs. Samsung IP war, Preet Bharara Robert Mueller coming after you–and the run of the mill, garden variety commercial dispute, including litigation as transactional negotiation by other means. When the big bad things happen, you have no choice but to open the war room and the checkbook, and sally forth. But when the smaller things happen, clients actually have a wide span of discretion in what they do–if they choose to do anything at all. So when we use the word “litigation” in this series, we are actually referring only to the non-life-threatening matters, and particularly to how much revenue they drive to law firms.

The “decline of litigation” is a hypothesis, not yet a proven fact, but we, as is our wont, will show you some data that seems to support this hypothesis.

This Part 1 will talk about some of those early data indicators and put them in the context of the changes in the legal services market landscape over the past decade or so. Further on in this series we’ll look at other developments influencing our theme including the relentlessly growing capabilities of AI, the rise of litigation funding, the growth of in-house departments, and what we are now calling “alt-law,” meaning essentially anyone and anything in the legal services sector that is not part of a corporate law department or a for-profit private sector law firm as we know them.

Let’s start with what you might call litigation 101. A primary reason we think it’s in long-run secular decline is simple: Clients hate it. And in this case clients are not only right, they’re rational.

It’s a zero-sum game–a straightforward transfer of assets/wealth from one party to another, with no increase in the value of the overall pie–and it comes at the price of a big cut taken out for lawyers, so it’s actually a negative-sum game from the perspective of the parties. Clients of BigLaw tend to be defendants far more often than they’re plaintiffs, so they get the short end of that net negative most of the time. To be sure, occasionally BigLaw clients win, but so do some gamblers in Las Vegas. In the long run you don’t want to bet against the house.

By contrast, corporate/transactional engagements are entered into with the hope of generating additional wealth for all parties concerned. If there’s not a willing buyer and a willing seller, it’s unlikely anything will happen. Successful deals leave everyone happy, and legal fees are at worst just an embedded transactional cost and at best the price of a critical service that opened new doors and created value in and of itself.

Second, historically litigation has been ghastly expensive. Law firms could exploit, or shall we say maximize the benefits of, the high leverage model in litigation almost as a matter of course. It was easy, and even justified in the name of zealous advocacy, to throw teams of associates at a dispute, who could bill their time against the matter all day every day for a long period of time. By contrast, few corporate transactions require similarly-sized teams, and they don’t tend to require them for so long. Deals close or they don’t (often against fiscal year constraints), but litigation can go on forever.

Other practice areas rarely offer up full-time single-matter engagements: Real estate, employment, private client services, tax, and IP all tend to force practitioners to jump from matter to matter to matter during any given day, which is inherently less conducive to racking up impressive hours.

But that was then and this is now: Now being pretty much the entire decade since the Great Meltdown. Clients are much more savvy, sophisticated, and discerning; growing more so every year; and there is no going back.

Third, litigation often harbors the risk of exploding reputational land mines; you don’t know what’s in the gigabytes of email until, well, until you know. (People say the darndest things.) And you may wish you’d never (had to) discover it. Bold clients might risk opening that black-ribboned box in order to press the fight and hope for the best, but conservative and prudent ones might prefer a quick known-quantity settlement.

Fourth–I hate to break this to you–a surprising amount of litigation is actually discretionary in the client’s mind. Must we sue that supposed patent/IP infringer? They’re small fry and will always be small fry, it’s not critical IP, we don’t want to give them the publicity: Just send a nasty letter and call it a day.

Finally, there’s wide consensus on the settlement value of many routine matters (common employment disputes, purely commercial contractual disputes over money) so if both sides are interested in moving things along a mutually satisfactory outcome should be quickly achievable. At the very least, scorched-earth, spare-no-expense warfare won’t be necessary. Less for the lawyers to do.

We promised data, and data you shall have.

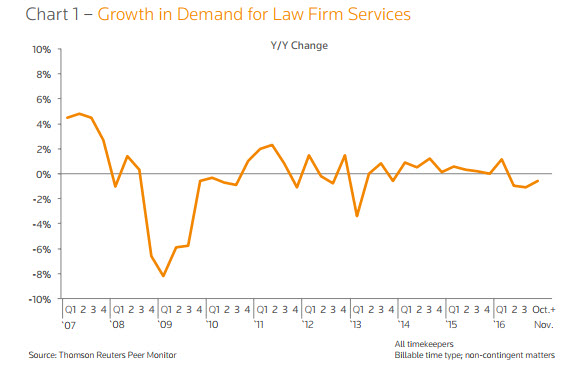

Here’s one of our favorite time-series from Thomson Reuters’ “Peer Monitor” showing “Growth in Demand” for law firms (defined as billable time for non-contingent matters) going back 10 years. You can see that it took a swan-dive from a healthy ~5% annual growth level before the meltdown to a low of nearly -10% but since then has been tracking right around +/- 0%. This is a classic pattern for a mature industry, to wit one characterized by a battle for market share among competitors.

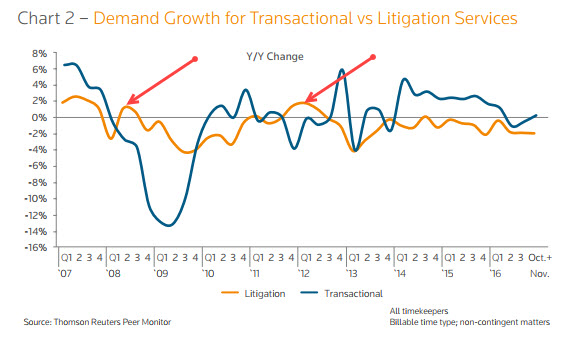

Next we segregate litigation from transactional services using the same dataset. You can see that since the meltdown–a full decade in the rear-view mirror at this point–litigation demand has never been positive with the exception of two brief blips above water.

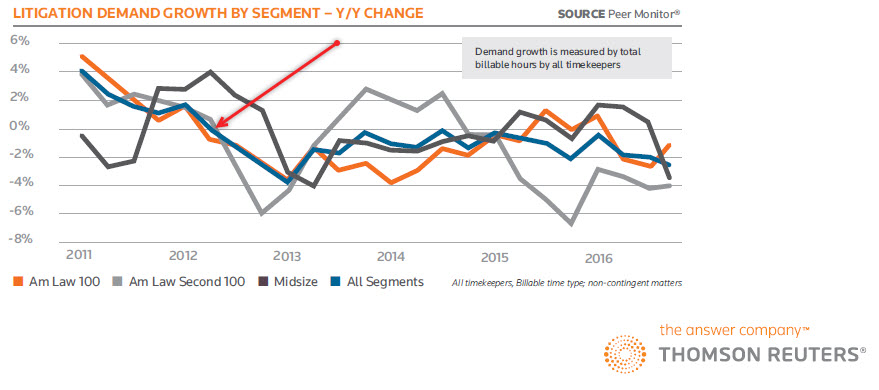

Finally, we zoom in on the past six years, breaking litigation demand into various law firm “sectors”–the AmLaw 100, Second 100, “Midsize” firms, and then “all segments.” This clearly shows that for the last five years the growth of litigation demand/all segments has been below 0%.

Without naming names, we will venture the opinion that a fair amount of what’s published and discussed about demand by practice area is anecdotal. Although there’s hopefully-untrue lore in journalism that “three examples constitute a trend,” we strenuously try to avoid that temptation.

And we would be the first to roundly affirm that this has been a discussion of averages; some firms will have enjoyed vastly different experiences–for better and for worse. Just because more Americans are obese than ever before doesn’t mean skinny people have disappeared.

Upcoming installments in this series will address additional evidence, as well as the long-run impact of newish developments on this landscape including predictive AI, litigation funding, and the changing composition of the sources of supply for “legal services”–of which law firms are a subset.

Bruce, would I be oversimplifying your argument to describe it as a suggestion that, although the number of disputes may be stable or even increasing, litigators believed that demand for their services was inelastic even as their fees reached and then surpassed the point at which the demand curve fell below the supply of lawyer time? Cases that a client might have been willing to bring for an attorney cost of $25,000 don’t make sense for the client if the attorney cost is $150,000. (Add a zero for New York City disputes.)

That’s definitely part of the client’s calculation. I can tell you from my decade in-house at Morgan Stanley that the finance folks were always on the back of the law department to “show some ROI.” Spending X to recover 2X might be justifiable, but spending X and then on top of that settling for 2X was inexcusable: “Why the (#(&$ didn’t you just pay them to go away and get it over with?”

The last chart is the most frightening. My first thought after reading the opening sentences was that your analysis might not consider the global expansion of firms. Litigation is largely an American phenomenon. As large firms expand globally, its makes sense to see the litigation’s contribution to firm wide revenue fall as a percentage. The last chart suggests that the AmLaw 100 is the only segment in which litigation is experiences some relative growth. My hypothesis would have suggested otherwise. I wonder how verins may impact these numbers?

James: Thanks for such a thoughtful observation. I especially appreciate your stating out loud, as it were, that you are capable of changing your mind if the data indicates one perhaps should! An altogether too scarce trait.

Your thoughts about lit as a US-centric phenomenon (indisputably correct) certainly has implications beyond the likely scope of this series. But thinking about the AmLaw 100 being the only litigation-growth cohort inclines me to believe that I might emphasize more forcefully the rather casual observation I made at the beginning of this column (bullet #3) about the stark distinction between “Holy S#%$!” matters and garden variety disputes. Reason and experience alike would both counsel that the “HS” matters go to the AmLaw 100.

Finally, re vereins: I will have to ask my friends at Thomson Reuters whether there are any vereins in their dataset. Stay tuned.

In response to the comment from BigLaw Lit, the last chart states that it is tracking total hours, not share of firm revenue, measured year-over-year. I read the chart to say that from mid-2012, the number of litigation hours in all segments is down about 4.5% (Y/o/Y declines of about -1.5%, 0%, -1%, and -2%, measured midyear), which the market has accommodated in some mix of (a) working fewer hours per lawyer, so that people who used to bill 2000 hours/year are now billing about 1900 hours, and (b) having fewer lawyers employed in litigation, so that about 1 of 20 litigation lawyers from 2012 is now out of work. If the largest of the firms are doing more foreign litigation, then the decline in American litigation is even sharper.

A long-time reader writes:

This would seem to validate “MidRange Guy”‘s deduction that 5% of 2012 litigators are now doing something else.

We have also seen an ongoing erosion in utilization, supporting his other point. Data to follow in this series.