The day arrived when I would bring all our phones to the Verizon store to check their compatibility with the network (Verizon runs on CDMA, AT&T on GSM, if you were wondering) and accomplish the big switch.

One of our phones was incompatible.

At the time, Verizon had been widely running ads that if you switched over to them you could get hundreds of dollars in credits toward a new phone, so I figured this was a non-event and we’d get a new phone for free. I walked over to one of the displays with the manager and he pointed out “the phone you want.” It was a just-released model of a perfectly fine-looking generic smartphone from a brand name manufacturer, so I said “fine, but I’ll just need to take it back to the office to let the person who’s going to be using it take a look for themselves—and this will all be taken care of since we’re coming over as new customers, right?” Nods.

At last we sit down at the desk to complete the switchover. This consumes well over an hour, punctuated by several finger-signings on an iPad agreeing to a lot of language displayed in pico-font.

Actually, it was punctuated by a lot more than that.

- To have a business (not consumer, remember) account we needed to sign up for something called “One Talk,” a service which provided some ill-defined benefits which I never did quite understand. Except I understood two things about it: (a) We would need it because otherwise Verizon couldn’t shoehorn us into their business customer template; and (b) it would cost $25/month.

- I had run a quick analysis of our monthly cellular data usage for the past year, and it was never over about 1.5 GB/month for everyone put together. We’re almost always within WiFI—at our office or at a client. At AT&T, we were on their smallest monthly plan (3GB); Verizon offers 2, 4, 8, 16, and unlimited. I said the 2GB plan would be more than fine. We were given the 4GB plan because “you don’t want to go down on data.”

- While I was waiting I decided to install the “My Verizon” app on my phone so I could look at the account right away. I told our rep I was doing that and even showed him the download in progress. He did not point out to me that it was a consumer-only app, and what I would actually need was “My Verizon for Business,” a different app entirely. (This had predictable consequences when I tried to look up anything about my account; it had no idea who I was.)

- The new generic smartphone, rather than being complementary, suddenly appeared as a monthly charge on a two-year contract.

- I reminded him we’d need the “network extender” device and he said he’d check to see if any were in inventory. I didn’t see or hear him check, and when I was finally about to leave he said he’d let me know about the extender and I left without it.

Act III:

Back at the office—now completely without phone service—I thought I’d take a moment to research how to configure their network extender so we could be up and running as soon as it arrived. My first question was how to register our numbers with it so it would reject every other Verizon subscriber in the area trying to connect and reserve its signal for us; we would be paying for it, after all..

I discovered that: This can’t be done. The Verizon device is open to any and all comers. This possibility seemed so far-fetched that it had never crossed my mind.

Actually, it’s worse than that.

Because it’s just a small box and not a grown-up cell tower, it’s rationed to seven simultaneous users, and those seven are—the first seven who happen to connect. No blacklists, no whitelists, no jumping to the head of the queue for us. As soon as seven Verizon phones have “found” it, it’s as good as an expensive paperweight for us. And Verizon clearly knows this; among the technical support Q&A’s on this issue were several plaintive notes form Verizon customer service people saying they’d been asking for a “whitelist” feature for a long time. I suppose this might work for a Verizon user who lives at the end of a country road in Vermont, but in Manhattan?

I don’t know whether this makes things better or worse, but as soon as I discovered this I called Bob and told him it was a dealbreaker; he said he was certain there was a way to do what we needed; “I’ll call you back in half an hour, max.” That turned out to be the last time we ever spoke (he never did call back).

Act IV:

When the doors opened the next morning, I was back at our AT&T store to restore our service. The rep I sat down with was friendly, competent, sympathetic, pulled up our terminated account and proceeded to reproduce it feature for feature, and was of great good humor. The biggest hiccup occurred when he needed my Verizon account number. Since I had yet to receive a bill I couldn’t get it off that, and when I logged into the “My Verizon” app that I’d installed (remember?), it had no clue who I was. He phoned Verizon.

At one point he apologized for things taking too long (half an hour as opposed to three times that long at Verizon) and asked if they could get me anything from the Starbucks across the street.

Here’s what else did and did not happen at AT&T:

- No unhelpful or condescending suggestions that they knew better than I what we needed.

- No pretzel exercises to fit us into an account model preferred by them but perhaps not by us.

- Truth in billing.

And he knew his market: He said “win-back’s” like our account were increasingly critical to AT&T since it’s a saturated market.

I appreciate your bearing with me through this somewhat extended saga (trust me, it felt endless when I was living it!) but I think it amounts to a parable with more than a few lessons for law firm client relations.

- First and foremost, listen to what your clients want and how they describe their problem. Respond to what their problem is rather than trying to shoehorn something you’re comfortable doing into “being” the solution for them. As we’ve written before, sell what they need, not what you prefer to make. If a critical priority for them is getting service inside a fortress-like century-old building and your “network extender” is a non-starter in a densely occupied environment because there’s no way to prevent freeloaders from monopolizing the signal first, don’t string them along.

- Closely allied: What you do for clients and how you serve them must be driven by their business priorities and by the outcomes they’re seeking to achieve. It’s turning things upside down to apply a model premised on the way your firm would prefer to do things (the pricey “One Talk” contract to fit us into a business account) regardless of its suitability to your client.

- Don’t act as though you know better than the client what’s in their self-interest (“you need to go up to 4GB”) if they’re well-informed and sophisticated and have done the research themselves to know where they stand. If there’s a material complication that they aren’t aware of, of course describe it and ask if it makes a difference to them, but if they know at least as much as you do, at least as far as that issue goes, shut up.

- A quite elementary point that shouldn’t need to be made but evidently must be: Be dead certain that everyone who talks to the client knows what your firm can and cannot do. Don’t be assumptive and don’t glide obliviously from the human and understandable “hope we can help” to the deeply unprofessional and alienating “sure, we can do that! …. Uuuh, well, maybe not [or worse, complete radio silence].”

- Also elementary: Be honest about pricing. If you’re advertising/communicating that a client can get a free phone when they transfer their account, don’t “forget” and charge them for it anyway.

A few other observations that may be a bit more subtle.

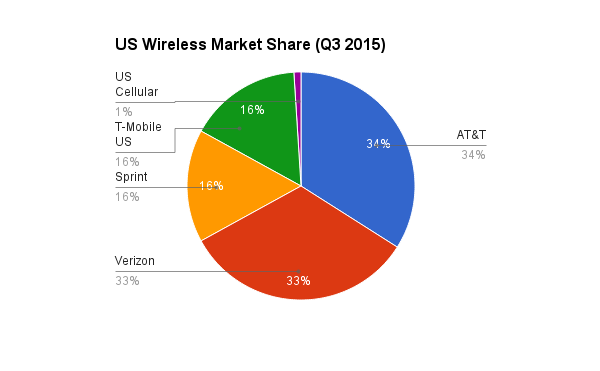

This article started, and it will end, with the fact that the US cellphone provider market is saturated; there’s excess capacity and it’s a battle for market share. That should sound familiar to anyone who’s been here since September 2008.

Second, my motivation for exploring a switch was driven by price. Until it wasn’t. (In the end, even if Verizon had rescinded everything it gratuitously added on to our account, they wouldn’t have been much cheaper.) In other words, price is a factor, but it may be less of one than you think or fear. Have more confidence on this score.

Lastly, did you notice something that was completely absent from this saga? Something that most law firm websites, marketing presentations, and pitches put front and center? I won’t torture you.

What was missing was: Quality. I take it for granted—as do I’m sure most Americans who don’t happen to work for either AT&T or Verizon—that the strength and reach of their cellular networks are for all civilian purposes essentially indistinguishable. It never crossed my mind to make “quality” even a trivial ingredient in my competitive evaluation. (I use the phrase “civilian” purposefully; we are definitely not talking life or death for Adam Smith, Esq., LLC.)

As long as you’re in the Big Leagues, which most people reading this are, whether on the global stage or in your little neighborhood market where it matters, clients assume quality; it’s not a differentiator.

You might take note of this.