Coming to the fore more prominently these days across a large portion of firms we work with and the industry overall is the issue of succession planning. It comes up in one or both of two contexts, (a) transitioning key client relationships from incumbent partners to the next generation, and/or (b) handing off leadership of the firm itself.

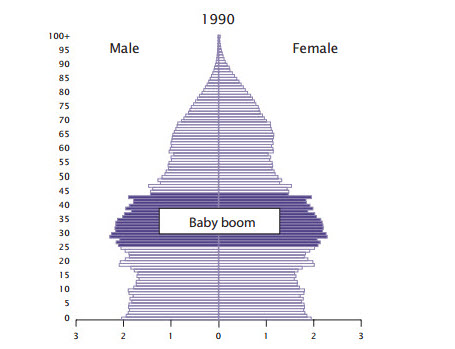

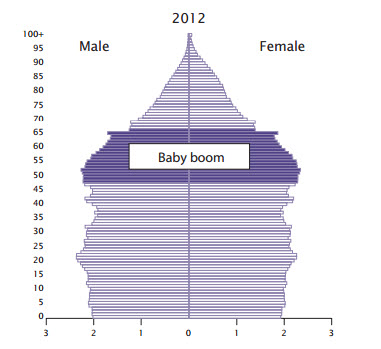

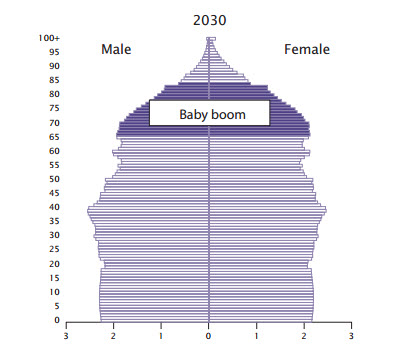

When this comes up, people tend to point to the baby boom generation nearing retirement, and everyone nods knowingly, but have you looked at the actual numbers? Since “going to the numbers” is our instinctive preference, we did, and thanks to the US Census (“The Baby Boom Cohort in the United States:2012 to 2060,”) you can see for yourself.

If you haven’t seen this type of visual display before, we’re quite fond it for the density and clarity of information it displays. It shows male (left of the midpoint) and female (right of the midpoint) population by age in years (vertical axis) and percentage of the total US population (positive numbers increasing to the left and to the right from the midpoint). A picture, or three, is indeed worth a thousand words.

1990

2012

2030

You can run, but you can’t hide.

Now, back to the topic at hand.

Beyond today’s scope is a discussion of when succession is in order; we won’t be debating the merits and demerits of term limits, mandatory age stepdowns, or when a client’s body language indicates you’d be well-advised to offer some new blood on the firm side. In what follows, simply assume that everyone agrees a transition is in order.

Another point of clarification: Client handoffs and leadership succession differ in terms of origin, implications, and optimal approaches, but they share sufficient kindred commonalities that for purposes of today’s essay we won’t, by and large, treat them separately. What follows, then, reflects our experience with these issues and some thoughts on how to address them.

Perhaps the best place to begin is to point out that “succession” is not the problem; “planning” is.

Succession is vital to an organization’s vitality, development, growth, and continuing maturation. No firm aspires to inbred stasis. (Some achieve it nevertheless, but that’s a subject for another day.)

The problem is that people in general and lawyers in particular prefer to deal with tomorrow…tomorrow. Hence we repeatedly find a shocking lack of planning for even the most foreseeable and consequential of transitions. Unfortunately, it can take years to carry out a smooth and careful hand-off of key client relationships or leadership of the firm itself, and when there are no plans in place—or no plan anyone is actually following or executing upon—then the hand-off will be improvised and can be chaotic and damaging to the firm. Then of course there are the crises: When a health emergency or an abrupt lateral departure (say) turn “transition” from a vague and foggy future event into a clear and present exigency.

We would be among the first to underscore that few issues in law firm management can be more emotionally fraught than succession planning, and surely this provides much of the explanation of why procrastination in addressing it is so endemic. But again, the problem isn’t succession itself, which provides an opportunity for rejuvenation and re-imagining of the functions and role in question; the problem is a preference for avoiding awkward conversations.

At the risk of making this awkward right now, our view is that that’s flatly inexcusable professional behavior. It’s immature and fundamentally self-indulgent at the cost of the firm’s and one’s colleagues long-run best interests. Avoiding conversations about critical transitions exposes your orientation as “me first” and not as “firm first.”

Because at the heart of succession planning is a future orientation. Preparing the way for the next tranche of leaders reflects one of the highest values the privilege of membership in a partnership or any organization calls for: Stewardship. An attitude of stewardship is nothing grander than recognizing the debt you owe to those who came before you in the institution and symmetrically carrying out your obligation to leave it better than you found it.

There can be a temptation to believe we’re all autonomous masters of our own destiny, beholden to nothing so fusty as institutional loyalty. This severely misapprehends the source of any of our accomplishments, such as they may be, and is unattractive bordering on repellent for good measure.

Succession is not only indispensable but re-energizing in the life of organizations; don’t thwart planning for it by ignoring the debt you owe your firm and your successors—unless, that is, you really don’t care if you have any successors.