This is a guest column by a very good friend of Adam Smith, Esq., Richard Rapp, who was President and CEO of NERA Economic Consulting for 18 years (1988-2005), during which time the firm grew to global scale. Richard now co-heads Veltro Advisors, a law firm compensation consultancy, based here in New York where he and his wife live. He has a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Pennsylvania.

For a law firm that is already large, do incumbent partners benefit from further growth? That question is on the minds of the managers of any sizeable, well-run law firm. There are, of course, benefits from growth apart from incumbent partners’ income gains – diversification, stability and the expansion of connections to new interests, practice areas and clients. Nevertheless, the importance of equity partner income is not to be denied so it is per-equity-partner profits on which we now focus.

Stories

Mere mental models– basically story-telling–offer no real insights. Incumbent partner incomes go up when the profit pool gets bigger and incumbents get to share in it. But when growth calls for investment out of incumbent partners’ pockets and when the extra profits (when they come) go largely to new partners, lateral or otherwise, there is little left over for incumbents. None of this helps much.

Facts

So much for mental models. What do we actually know?

For a factual examination of the question, we turn to the American Lawyer 100 and 200 data sets which reports measures of law firm size and profitability, including per-lawyer and per-partner averages by individual firm. Since we are examining only the 200 largest U.S.-based firms, no inference drawn from these numbers can be applied to smaller firms outside this group. Studying the biggest firms may contribute to the intuition of smaller firms’ managers but only indirectly. Every statement that follows should be prefaced by the phrase: “For firms in the top 200,” since what is true for them may not hold true for smaller firms.

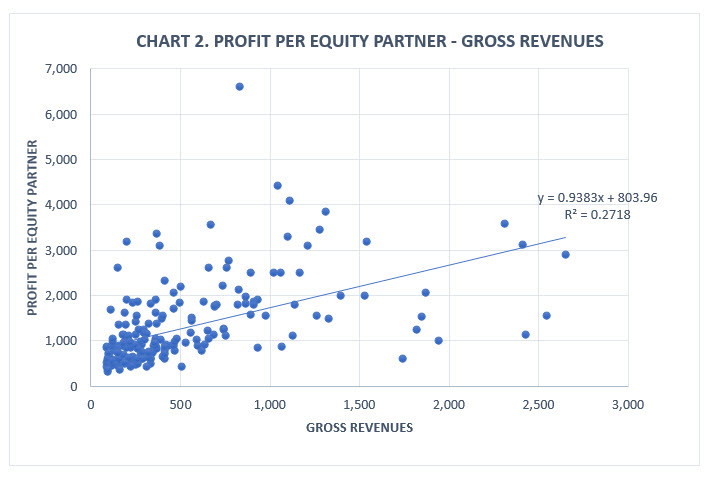

Here are the charts that tell the story:

Turning to firm averages that reflect the profit yield to individual partners at the top 200 firms, we observe a strong relationship between profit per equity partner and revenue per lawyer, as expected. The more that each lawyer of every category earns for the firm, the higher the incomes of the owners—the equity partners.

Note the two-way relationship between these measures: Higher utilization and billing rates create more income for partners while partners who bring in and oversee profitable business for the firm create the demand that supports higher rates and more hours per lawyer. There is no generalizing across firms about which direction of causality dominates.

Revenue per lawyer is unrelated to firm size. There are firms of every size within the ALM 200 which enjoy high demand, high billing rates and so high revenue per lawyer and there are firms of every size which do not.

So why doesn’t firm size matter at all with respect to profits per equity partner? Is it because any advantages of a large firm, such as economies of scale, diversification, access to resources, etc. are negated by other factors? If so, what “other factors” are there? Could it be opponents, knowing who they’re up against, bring their “A” game? Or maybe a large firm’s ability to boost profits per equity partner is tempered by increased bureaucracy, sluggishness and more difficulty in maintaining a unified organization?

Out of curiosity, why are most BigLaw firms largely devoted to hourly billing? And why don’t we see many large firms focused on personal injury? Seems like the personal injury practice of law would benefit greatly from having large firms.

Richard Rapp and I briefly corresponded about these questions and his reply, in which I thoroughly concur, follows: